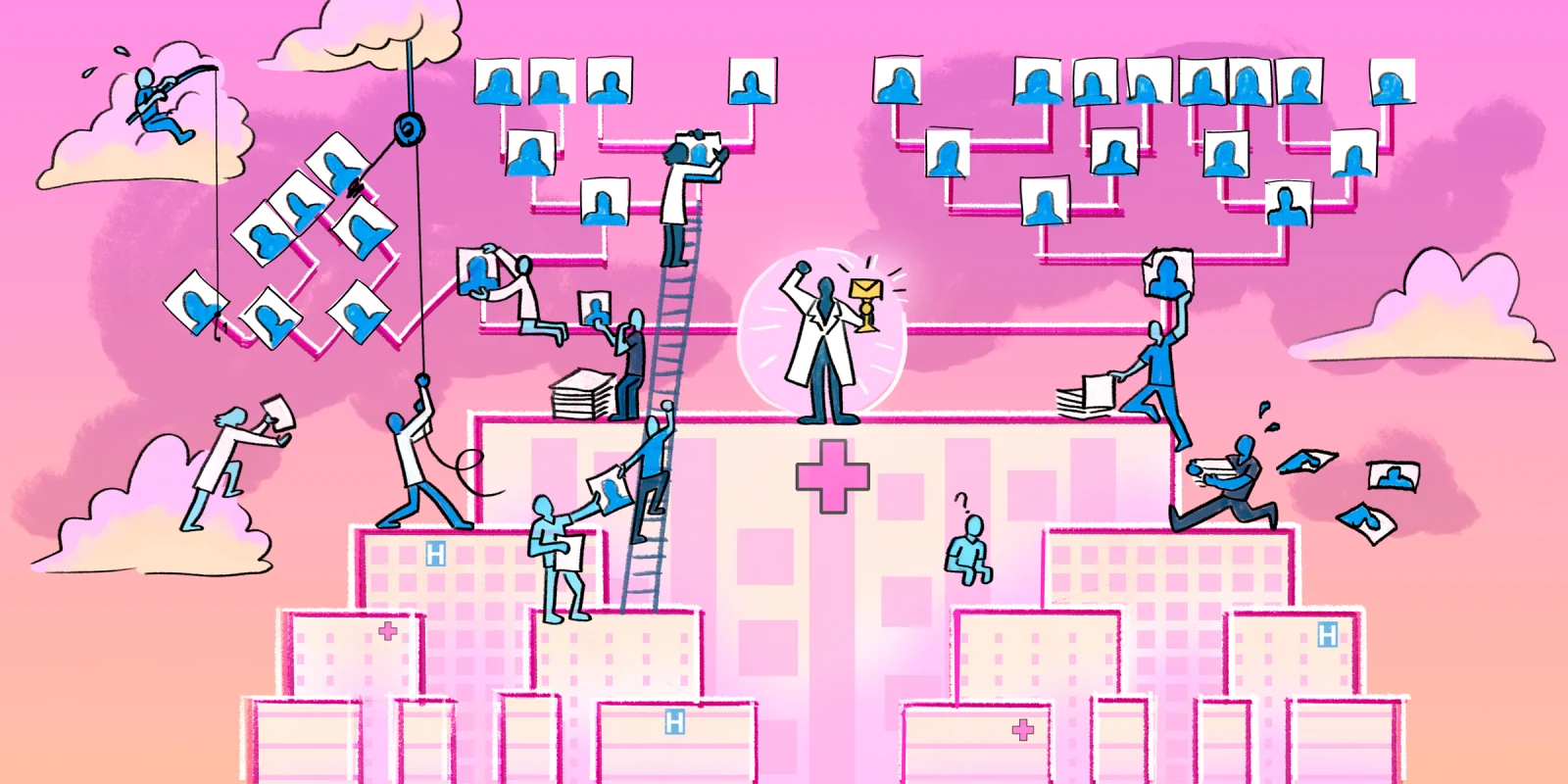

Match season. It’s a time of year filled with mixed emotions. From the faculty point of view, Match season usually starts with a frustrating and seemingly endless rank meeting, where the program finalizes its residency applicant rank list based on long-winded and sometimes conflicting input from all faculty members who participated in interviews. This is the way it’s been done for decades and the way it will likely proceed for decades at several programs. But I do believe there is an easier way.

The classic rank process is flawed for several reasons, and these flaws are, in no small part, what usually make the meeting so long and frustrating. The first is that, with the exception of the program director and in some cases the associate program director, everyone in the room has only interviewed a fraction of the applicants. This can result in a heated comparison of apples to oranges. It’s easy to argue that your favorite applicant, currently listed in the No. 12 spot, should absolutely be in the top 10, especially if you never interviewed the applicants who would have to get demoted to make that happen. This can create a battle of wills among faculty rather than an objective assessment of what each applicant brings to the table. An applicant might move up or down the list based on how effectively their randomly-assigned interviewers promote them, a matter of luck rather than merit.

The next flaw is that we, as faculty, are all subject to bias. The easiest way to think about this is in relation to the applicant’s research accomplishments. The faculty’s assessment of this section of the applicant’s CV is often deeply rooted in their own experience with research. For example, a purely clinical faculty member who never took a personal liking to research may advocate putting an applicant with zero first-author publications at the top of the list based on other attributes, whereas if a faculty member with an extensive research background had interviewed this same applicant, they may have recommended ranking them lower.

Third, I — and likely most people — find it harder to remember an interview that occurred two and a half months ago when compared with an interview that occurred last week. Conversely, I have seen faculty get very attached to an applicant or two that they meet early in the process, and then convince themselves that no one who follows can measure up. Either way, these time-based biases can unfairly and unintentionally influence where applicants land on the rank list.

Finally, we’ve all made the mistake of getting carried away with the interview alone. It’s hard to remind yourself to look at the whole picture when you have a dramatic personality click. “I’m assuming everyone here today already passed the academic bar, so…” I’ve heard it. I’ve said it. But applicants are more than their interviews, which is why they take the time to submit a full CV.

To get around these flaws, I have a few easy recommendations. First, use an objective ranking system for each portion of their application. For example, have one person assign a score to each applicant for their research. This mitigates individual bias and ensures a consistent scoring system across the cohort. I recommend taking the same approach for a variety of otherwise subjective data points such as letters of recommendation, transcript grades, extracurriculars, awards, etc.

Next, I recommend having a brief ranking session at the end of each interview day rather than one big meeting at the end. This avoids the issue of various faculty fighting about applicants interviewed on different dates and also ensures decisions are made while interviews are still fresh in the minds of faculty. During this meeting, don’t assign applicants an actual rank; assign them an “interview score” on a one-to-five scale. Once interviews have concluded and everyone has a score for every category, simply weigh each category with regard to what is most important to your institution. For example, an academic program with a strong history of contributing to cutting-edge medical technology may weigh research more heavily than a community program focused on excellent clinical training. Once a weight has been assigned to each individual score, calculate a weighted average score — a composite score — for each applicant. Voila! Your rank list is created for you. Of course, it is important to note during the post-interview rank meetings whether any applicant really stands out. These individuals can be marked as “rank to Match” and pulled to the top of the list as long as it doesn’t conflict too dramatically with their final weighted composite score.

In the end, no matter how you create your rank list, it’s always exciting to submit this to NRMP and even more exciting to finally get your Match results. After all, these applicants will soon be residents, and your residents will soon be attendings — and these young attendings are the future of medicine.

Acknowledgement: Although I am sharing the merits of this system here, all credit for its development goes to my predecessor and mentor, Gary Marshall, MD.

How else might the residency selection process be improved? Share your insight below.

Dr. Danielle Pigneri is a trauma and acute care surgeon practicing in the Dallas-Fort Worth metroplex. When not working, she enjoys her other job, being a mom to two sweet young children. Dr. Pigneri was a 2022-2023 Doximity Op-Med Fellow, and continues as a 2023-2024 Doximity Op-Med Fellow.

Illustration by April Brust and Jennifer Bogartz