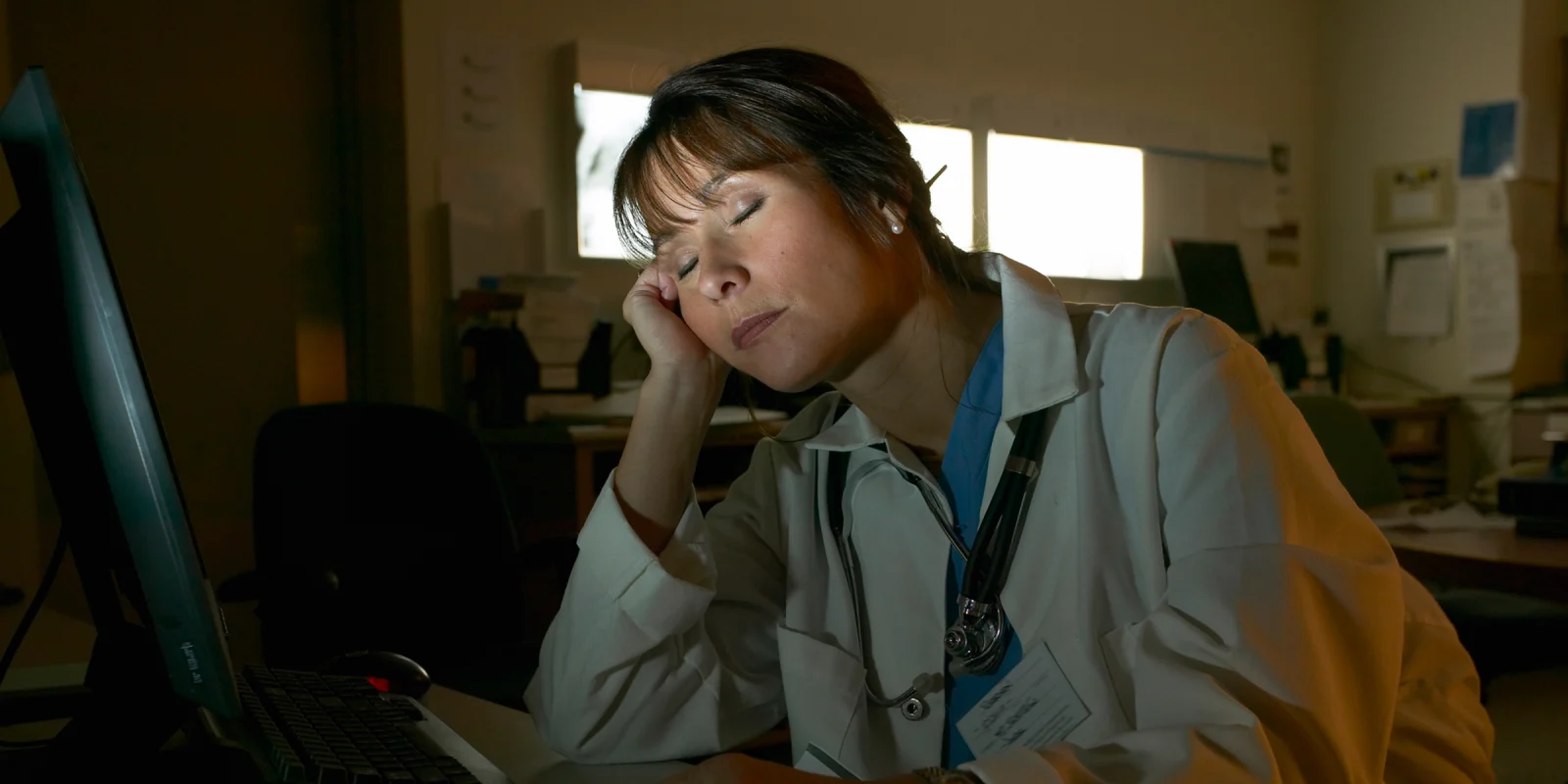

I had been awake for nearly 24 hours working in the ICU. Earlier that night, one of my patients died unexpectedly. Breaking the news to his family was still a fresh wound. Later, amidst the exhaustion and frenetic pace of my work, I made an error by ordering a patient a medication she wasn’t meant to receive. I was terrified I had harmed her. I hadn’t had a moment to rest my head on the desk, let alone sleep.

By hour 22, I still had five admission notes to write — critical patient information was stored in my head and needed to be entered into the EMR. I fantasized about curling up under a blanket on the floor.

I wondered if my patients would feel safe if they knew how exhausted and depleted their doctor was. I wondered what they would say to hospital administrators and medical education leaders who insist these work hours are not only safe, but good for me and my colleagues.

My friends and family outside of medicine are routinely horrified that resident physicians are required to work 24-hour shifts, often every third or fourth day, while providing life-saving medical care. They ask me why this is still common practice.

Resident work hours have been an active area of public debate for decades. Amidst a global pandemic that has put even more strain on residents, a new study in NEJM is bringing the issue of long shifts to the forefront of medical education discussions again.

In 1984, 18-year-old Libby Zion died at a New York City hospital. Her father, a prominent journalist, attributed her death in part to the fact that she was cared for by sleep-deprived, inexperienced resident physicians working 36-hour shifts with inadequate supervision. The story became national news and an inflection point in medical training.

In 1989, my area of specialization, internal medicine, instituted an 80-hour work week limit, but 30-hour shifts were still permitted. The medical establishment has maintained 30-hour shifts are good for patients because they reduce hand-offs between residents, and good for residents because they provide the opportunity to observe patients’ clinical course and the effects of treatment strategy over a sustained period.

However, multiple studies have shown that the rate of medical errors increases with 24-hour shifts. Residents working prolonged shifts are more likely to sustain needle stick injuries and be involved in motor vehicle accidents. In 2008, after an extensive review of the literature on acute and chronic sleep deprivation, the Institute of Medicine recommended that if 30-hour shifts are to continue, residents need to be guaranteed five hours of sleep. However, that guaranteed rest time has not been effectively put into practice. With good luck, I have occasionally gotten five hours of sleep. But I’ve also had entirely sleepless nights.

In 2011, the ACGME mandated that the shifts of first-year residents, known as interns, be limited to 16 hours. Second-year residents and beyond were permitted to provide continuous clinical care for 24 hours, with up to an additional four hours for hand-offs to other team members.

Additionally, the ACGME allowed an exception to the 16-hour work limit for interns participating in the iCOMPARE research trial. The study’s aim was to determine how “flexible shifts” of up to 30 hours for interns versus the new standard 16-hour shifts affected education, sleep, and patient outcomes. The findings of iCOMPARE were published in NEJM in 2018 and 2019, and have been used to justify the latest changes in resident work hours. Yet the studies have important flaws.

For patient outcomes, the study measured 30-day patient mortality and hospital readmission rates and no difference was found between programs with shifts up to 30 hours versus shorter, 16-hour-shifts. This finding has been mentioned in the press, and in the researchers’ talking points, the claim is that longer shifts don’t negatively impact patient outcomes in general. However, the outcomes measured in the trial don’t capture the day-to-day experiences of interns’ clinical care. They don’t tell us if the more sleep-deprived interns made more medication errors, or if they took longer to recognize clinical changes in their patients, or if they were less attentive to patient experiences like pain control.

The sleep outcomes the researchers measured were also flawed. They focused on average sleep over two weeks. As one of the researchers, Dr. Mathias Basner, explained, “Interns in flexible programs were able to compensate for the sleep lost during extended overnight shifts by using strategic sleep opportunities before and after shifts and on days off.” This reasoning defies what most human beings know from lived experience: even if you get extra sleep on the weekend, pulling an all-nighter is an acute form of sleep deprivation with a negative impact on alertness, response time, and mood.

The iCOMPARE study did, however, find one significant difference between the two groups with different hours: the interns’ own experiences. Interns with longer shifts reported a negative impact on their morale, health, and overall well-being, as well as on educational experiences like pursuing research and teaching medical students. With longer hours, interns were roughly twice as likely to feel that their fatigue negatively affected their personal safety and their patients’ safety.

Remarkably, despite these concerning reports from the interns themselves, the study results were actually used to justify the longer hours and reverse a prior cap of 16 hours for interns. Meanwhile, 80% of respondents in a public survey reported that they would want a different doctor if they found out their doctor had been awake for over 24 hours.

On June 25, NEJM published a new study comparing the rates of medical errors made by resident physicians working 16-hour shifts versus 24-or-more-hour shifts. Overall, they found that the residents working the longer shifts actually made fewer errors. However, when they controlled for how many patients each resident was responsible for, the results were inconsistent. At hospitals where residents already had high patient work loads, they made fewer mistakes with longer shifts. But when residents had lower patient work loads, more errors were made on longer shifts. As the number and complexity of patients cared for is a major factor in patient safety, these inconsistent results make it difficult to draw conclusions about work hours from this study.

Medicine strives to be evidence-based. The work-hour studies are intended to provide a rational scientific approach to making resident schedules. But the work-hour studies thus far are flawed. Those engaging in discussions around work hours need to be aware of these studies’ limitations.

In addition to being evidence-based, decisions around work hours must also be ethical. When resident physicians speak out about long hours, our dedication to our patients and the profession are often called into question. That makes it very hard for us to bring our own difficult experiences into the conversation. For many, speaking up is not worth the risk. It is only now, having completed my three-year internal medicine residency and matched at a pulmonary and critical care fellowship that does not require 24-hour call for its fellows or internal medicine residents, that I have the professional security to address this issue so publicly.

I have looked into the studies around work hours so that I may be an informed participant in this discussion. But I worry that the framework of evidence-based medicine applied to the question of work hours is a way of seeking scientific justification for the exploitation of vulnerable workers with little power to advocate for themselves. Ultimately, I am opposed to 24-hour in-hospital shifts first and foremost because they are unethical. Requiring resident physicians to work more than 24 hours consecutively, without any guaranteed time to rest, is simply inhumane. As medical educators continue discussions on work hours, I urge them to remember this is not just a question of evidence, but one of ethics and how those with power treat those who rely on them.

Colleen M. Farrell, MD is a pulmonary and critical care fellow in New York City. Follow her on Twitter @colleenmfarrell.