I stood waiting for the shuttle at a busy intersection after finishing my emergency room shift. Within a minute of turning up the volume on my headphones, drowning myself in music, I saw an obese man at the bus stop suddenly collapse. I removed my backpack and ran to him, the fastest I have ever run in my life. His body was shaking violently. I waved and yelled to a nearby police officer.

I stood waiting for the shuttle at a busy intersection after finishing my emergency room shift. Within a minute of turning up the volume on my headphones, drowning myself in music, I saw an obese man at the bus stop suddenly collapse. I removed my backpack and ran to him, the fastest I have ever run in my life. His body was shaking violently. I waved and yelled to a nearby police officer.

"Hey! Help me over here, officer!!"

I wrapped my arms across the man’s back to pull, the officer appeared to push, and we slowly rolled him over onto his back. I recognized him immediately; he had been a patient in the ER earlier that day for a breakthrough seizure. As we pulled him upright against the bus stop sign and leaned him forward, foam quickly formed and exited out of his mouth.

"Sir! If you can hear me, what is your name?"

No response. His movements were jerking and uncontrolled. I knew we had to get him into the ER, somehow.

"Look after him. I will be back with a chair," said the officer. He ran through the ER sliding doors — it was only the man and me.

Earlier that morning, around 10:30 a.m., I was with Team A seeing patients at one end of the ER bay. At the other, a man in his 40s, wearing baggy jeans and a Cowboys sweatshirt, was rushed to an open bed. He was Team B’s patient, and he was actively seizing. The immediacy of his condition distracted my attention, and I was aware of his presence continually. An hour later, at 11:30 a.m., I saw a towering woman storm into the ER and demand to speak to the head person.

"Why is my brother being discharged?! He hasn't had a seizure for two years on meds, but out of all the days, he has one today. And you people are discharging him without finding a reason?!"

"We have stabilized your brother and he has regained consciousness. If he begins seizing again once home, please call 911 immediately," I overheard a Team B resident say to her. The woman cursed us all, accused doctors of putting bandaids on problems instead of finding real solutions.

She left the ER abruptly, and I didn’t see her again. About 20 minutes later, the man left the ER, too. As he walked past me, we made eye contact and I immediately sensed that he was not entirely himself. But he was not a patient on my team and as a medical student, I was scared to overstep. Looking back, I should have spoken up for him.

Back at the bus stop, the officer returned with two nurses and a wheelchair in under 30 seconds. He was slowly regaining consciousness, but as soon as we finished strapping him into the chair, he started seizing again. Then he started seizing more violently. At that very moment, I thought he was going to die.

"Let's move now!" said a nurse.

I found myself steering the chair into the ER and through the winding hallways. At sharp corners, I slowed the chair down, avoiding the people that stood by and watched. As we made it to the shock room area, a doctor motioned me to Shock Room B. We removed the straps with great haste, lifted the man onto the bed, and strapped his torso, arms, and legs down.

"We'll take it from here," the physician told me in the calmest voice I've ever heard in an emergency. I anxiously stood outside the shock room as I witnessed the orchestra unfold. One person pushed medications, another started an IV, someone was checking vital signs, another was calling family members to get a history. I'd never seen anything like it. A few minutes into the action, a resident was asking me for my story to include in the patient's note. I told her everything I could remember.

"Here is your backpack, by the way, thank you so much for staying around and being the first responder." I still had adrenaline pumping through my veins, and all I could do was nod.

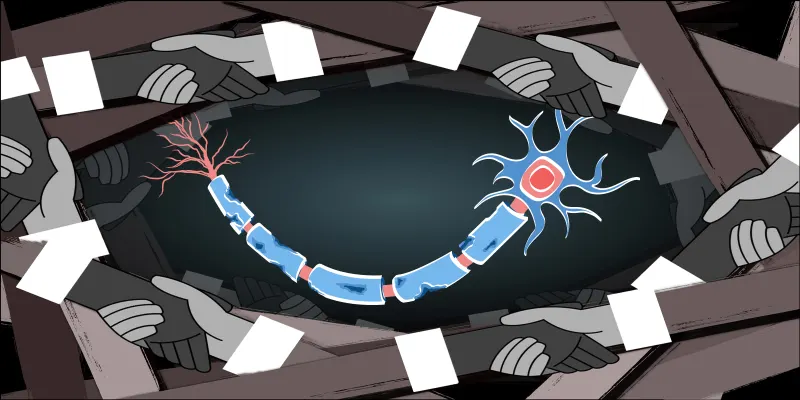

When I returned to the ER the next day, I learned that the man was transferred to the neurology inpatient floor for further assessment, probably an EEG and reevaluation of his seizure medications. I don't know what became of him, but I hope he is well.

In a few short years, I will be a resident physician. I will encounter more situations like the one I just described. And even though I never wished for this kind of experience, I am grateful I experienced it. I am even more grateful that the outcome was positive — because sometimes it isn’t; sometimes it’s lethal.

The one lesson that I will carry with me forever is to always be aware of what’s happening around you, because you do not know when someone will be in need of your immediate help.

Ton La, Jr. is a MD/JD candidate at Baylor College of Medicine and the University of Houston Law Center. He is applying to Internal Medicine residency programs Fall 2020. He sits on the American Medical Student Association Board of Trustees as the Vice President for Membership and previously served as the Student Editor of The New Physician.

Image by bob boz / Shutterstock