As a hospitalist in New York City taking care of COVID-19 patients — and a clinical ethicist — I see the PPE shortage from two perspectives: that of the clinician fearful of becoming infected, and that of the ethicist understanding the need to take care of our patients.

As a hospitalist in New York City taking care of COVID-19 patients — and a clinical ethicist — I see the PPE shortage from two perspectives: that of the clinician fearful of becoming infected, and that of the ethicist understanding the need to take care of our patients.

Seasoned clinical ethicists have said that clinicians should take care of COVID-19 patients without PPE barring any extraordinary risk to themselves. Others have invoked the Rumsfeldian theory of war in which you go to the battlefield or front lines of patient care with the equipment you have. Still others say that we are compelled to treat patients without PPE unless there is inadequate burden-sharing at the institutional, governmental, or public levels (this particular perspective was voiced in personal communications with the Clinical Ethics Consultant Affinity Group). And many members of the public leave it at: “It’s what you signed up for’ — which is not only an oversimplification of the matter but oversimplification that unfairly places the burden on the individuals at the front lines of health care.

Is taking care of patients without adequate PPE an extraordinary risk for the clinician?

The clinician’s fear about COVID-19 rests in the indiscriminate manner in which the disease wreaks havoc on the lungs of the unlucky few, sometimes unrelated to age or comorbidities. Those forced to take care of patients without adequate PPE are far more likely to become infected. And caretakers may have the illness with little or no symptoms. According to a talk by Tom Frieden, the former director of the CDC on April 14, there were 10,000 health care workers with confirmed COVID-19 infections. In my very own city, now the U.S. epicenter of the pandemic, over 100 doctors and nurses have died, two-thirds of those in Italy. If we had a way of knowing which of us were higher risk (beyond the obvious risk factors of age, obesity, and other comorbidities), we could remove them from the front lines. The fact of the matter is that the risk of COVID-19 infection to some health care workers is extraordinary — we just can’t always predict which ones in particular.

Does taking care of patients without adequate PPE violate the tenet of “First Do No Harm”?

Furthermore, the risk does not just stop with us. By caring for a patient without PPE and becoming infected, we increase our chances of passing the illness along to our coworkers, those we encounter on public transportation, the family members we live with, and, for those of us also taking care of non-COVID patients, those patients without the infection. The moral distress associated with harming others, however unintentionally, cannot be discounted. And if we become patients ourselves, we further deplete the workforce.

What should clinicians do if faced with a PPE shortage?

Given the PPE shortage and the increased risk in treating patients without PPE, many providers have attempted to obtain their own. Stories abound from around the country of nurses being suspended or fired (or threatened with suspension or firing) for refusing to work without PPE or for bringing their own PPE (1, 2, 3, 4, 5). For many nurses, it was damned if you did, damned if you didn’t. And it’s not just nurses — nor just doctors and other direct care providers; professionals of all stripes are likely to refuse to interact with infected patients without adequate PPE, which will further exacerbate the health care worker shortage and negatively impact patient care. In short, workers will be spread even thinner than they already are.

Is this what doctors and nurses signed up for?

There are those who argue that this is what doctors and nurses signed up for when they started medical and nursing school. The truth of the matter is that taking care of contagious patients without adequate PPE during a pandemic is not what they signed up for at all. It didn’t cross their minds, or those of their interviewers or professors, and thus it was neither mentioned nor discussed.

“Volunteering” doctors and nurses to work without adequate PPE violates the principle of informed consent and impinges upon clinicians’ right to autonomy. And it’s not just doctors, nurses, and physician extenders who did not sign up for this. Emergency responders, respiratory therapists, janitors, and food service providers also did not sign up for work in these circumstances.

At the end of the day, we don’t want to have to choose between patient care versus personal health, and the health of co-workers, families, and patients. It may seem shocking to some, but health care professionals do not have a duty to treat patients without adequate PPE. At the level of the individual, many health care workers want to continue to provide care to patients — but desire should not be confused with duty. So: Do medical centers, local, and federal governments have an ethical obligation to ensure health care workers have adequate PPE? It’s admittedly easier said than done right now, but the answer is a resounding yes.

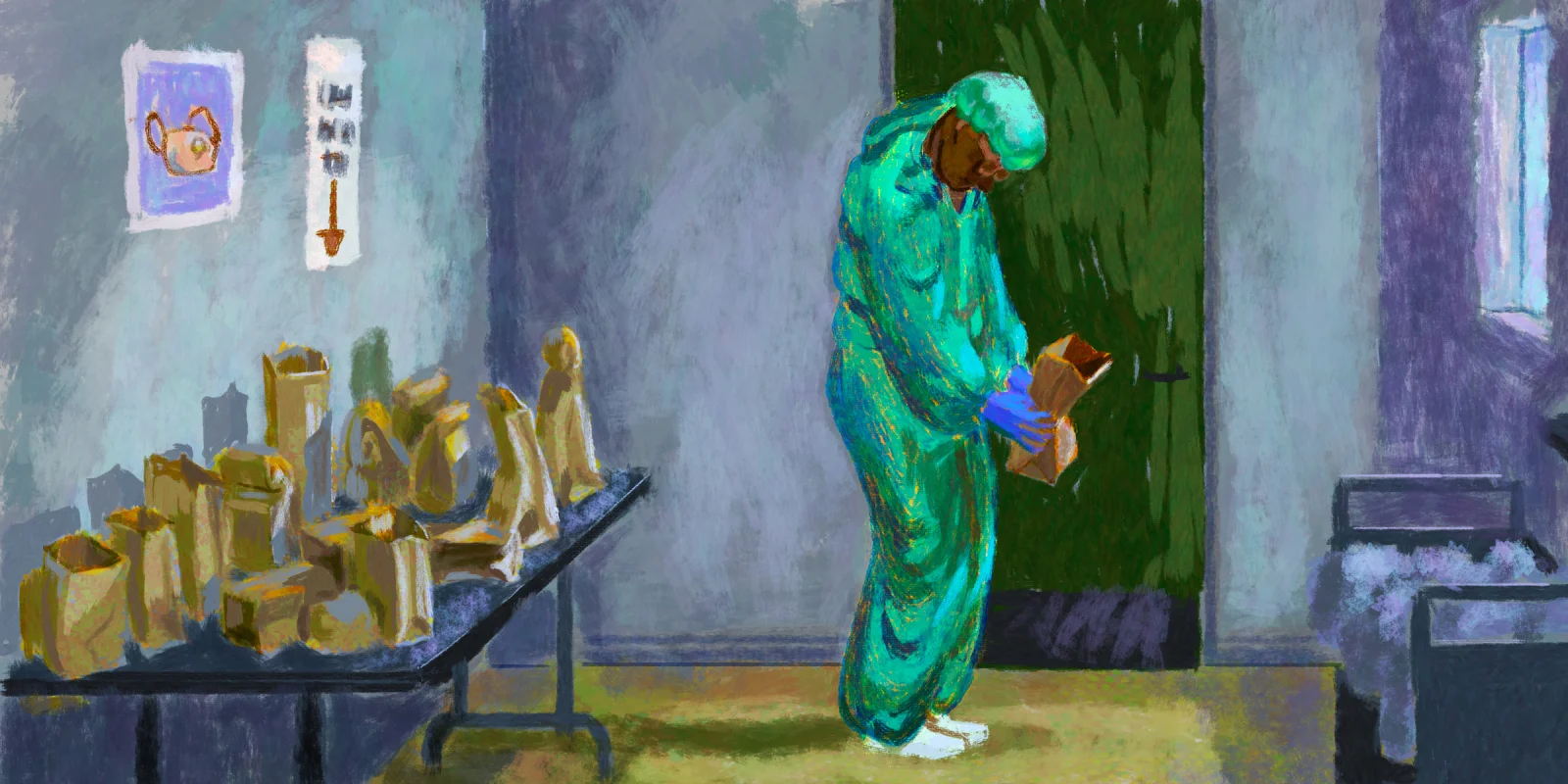

Illustration by Jennifer Bogartz

Click here to see more perspectives on COVID-19 from the Doximity network.

Click here for up-to-date news about COVID-19 on Doximity.