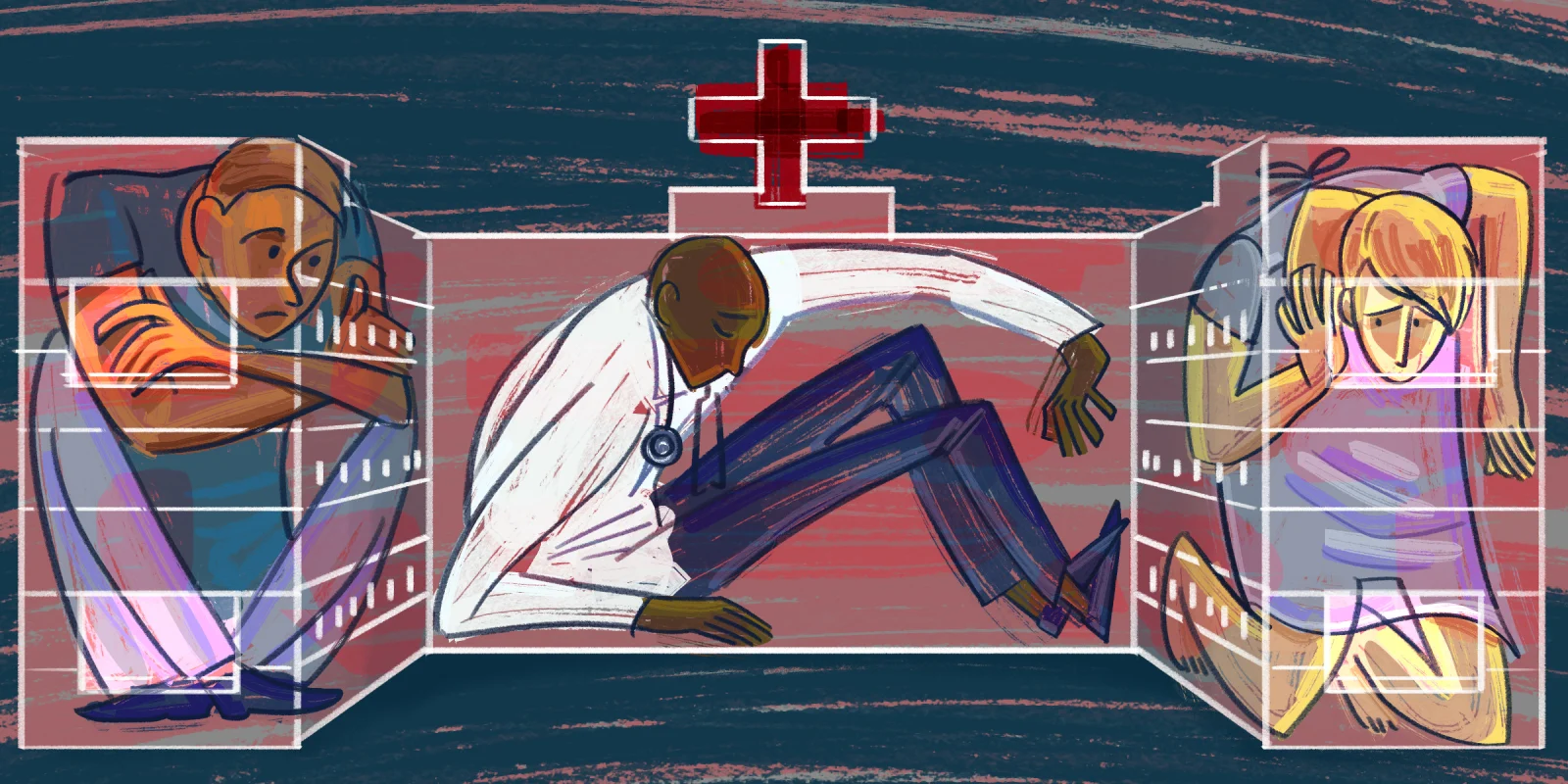

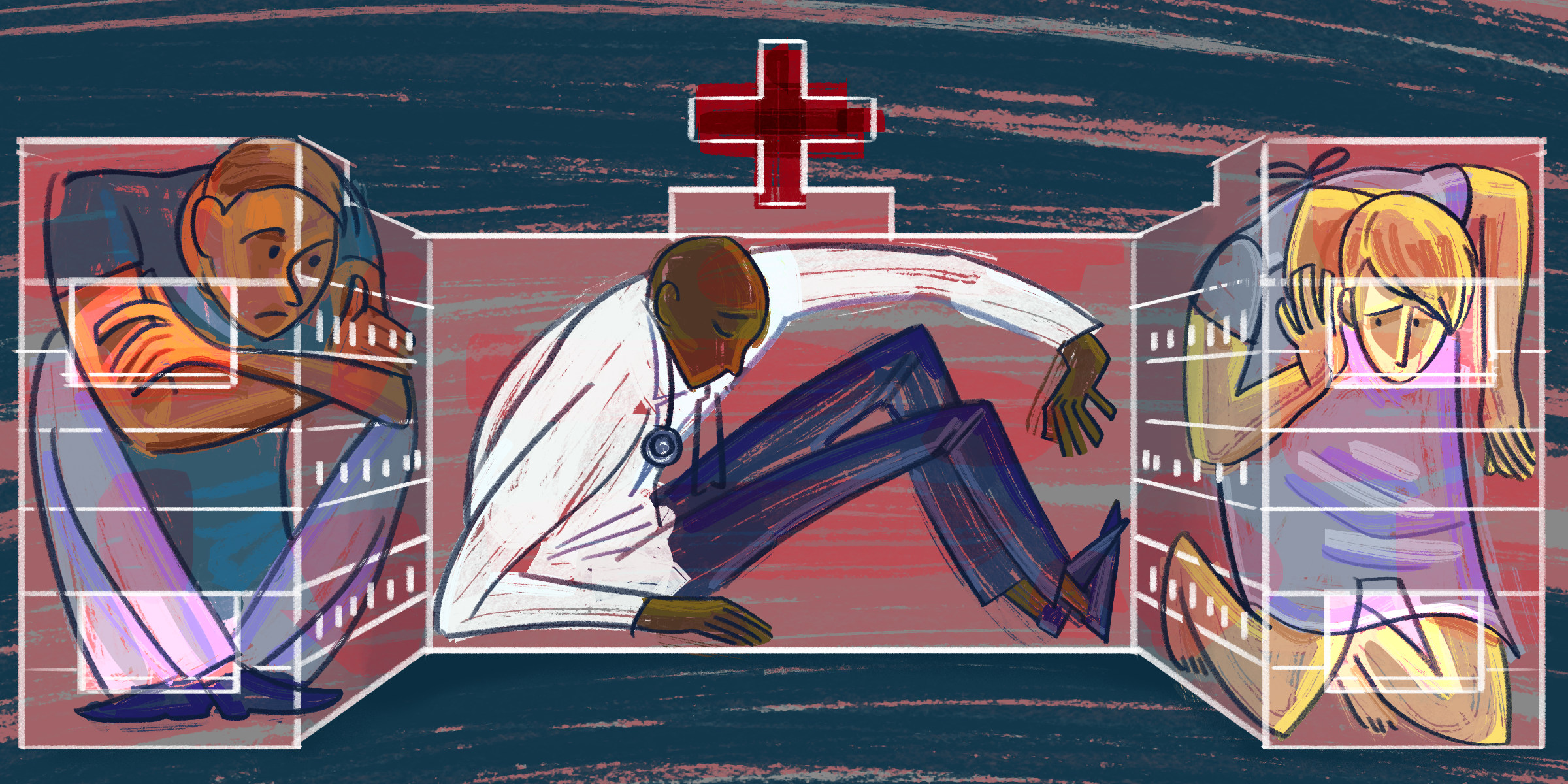

Hospitals have caught the design bug, but the bug is a mutant. Hospital architects are trying but not actually practicing true human-centered design: design that uses empathy, ethnography, and introspection to create meaningful solutions. Rather, they are borrowing successful ideas from other industries and forcing them into hospitals.

As hospitals are part of the larger health care system, hospital design is intrinsically linked to health care design. Health care, in modern times, is an industry that has become overinflated with demands from politicians, pharmaceutical companies, patients and many other stakeholders. In order to keep pace, 21st-century health care tries to do everything but ends up doing nothing. The dark secret behind new hospital designs is that health care is losing its identity.

“Health care” has always been an inapt term. A better term would be “sick care.” Sick care traces its roots to ancient Egyptian temples, which were the first institutions to offer medicinal cures. Christianity drove the centralization of patients under one roof, leading to the creation of hospitals. Until the 18th century, hospitals were closely tied with religion, charity, and education. But with the rapid growth of technology in the 19th century, the medical profession was reorganized along bureaucratic lines.

One of the most monumental pieces of legislature in modern health care history is the 1946 Hill-Burton Hospital Survey and Construction Act, which is responsible for much of our current infrastructure. Hill-Burton gave health facilities grants for construction and modernization. Around the country, a focus on function and efficiency led to the many sterile, cookie-cutter, fluorescently-lit buildings that we now know as modern hospitals. By 1975, Hill-Burton was responsible for the creation of nearly one-third of U.S. hospitals. Unfortunately, these buildings did not lend themselves to retrofitting. But quickly, advances in medical technology made Hill-Burton hospitals obsolete.

Today, visits to hospitals are not just unpleasant but also dangerous. Hospital-acquired infections are among the most common complications hospitalized patients experience. As hospital care costs skyrocket and technology evolves, patients are starting to seek care elsewhere. One place where patients look is in the wellness industry, an industry that is much more accessible and far more profitable but already saturated with luxury retreats and boutique fitness studios. The wellness industry, with its luxury spas and soothing meditation centers, offers much more pleasant experiences than what is currently being offered by our obsolete health care system.

In an attempt to compete, hospitals are placing a renewed focus on design and the patient experience, broadening their services while attempting to provide “health care” in addition to “sick care.” The design ideas are obvious: soothing music, soft lighting, refreshing views, and lots of artwork. Other exemplary hospitals are taking design one step further. At the NewYork-Presbyterian David H. Koch Center, patients enter a beautiful, open lobby modeled after 11 Madison, Goldman Sachs, and other NYC architectural beauties. While waiting for surgery, patients are offered meditation classes, and loved ones have access to lounge areas equipped with WiFi. Professional greeters and on-demand meals 24-hours a day cater to patients at the Henry Ford West Bloomfield Hospital. The appointment center is modeled off of airline reservation portals, and the building resembles a retail mall with an upscale grocery market and live feeds of the Detroit Symphony orchestra.

Health care facilities all over the world are starting to resemble structures in other industries — luxury spas, five-star hotels, airport lounges, and upscale malls. The Mass Design Group, for example, built a hospital in Rwanda that made headlines after the New York Times wrote that it was “way too cool to be a hospital.” This begs the question: “What is a hospital in the 21st century?” The answer is unclear.

Behind the amalgam of a spa-hotel-lounge-mall hospital-like structure is an industry that is losing its core identity. Health care is a conglomeration of services without a cohesive, unifying purpose. Once a gathering place to provide medical care to the sick, the scope of 21st-century hospitals is extending far beyond sick care. Arguably, hospitals are even beginning to shift away from sick care in order to focus on health, prevention, and wellness. If we continue designing without introspecting, sick care may cease to exist.

Great architecture and beautiful design are not replacements for basic care. Though studies show that smart designs can improve patient outcomes, smart designs do not cure disease. Further, most truly sick patients want to be at home, not at five-star hotels. They want privacy, independence, and other comforts found only in familiar environments. Thus, rather than building luxury hospitals, we need to build systems in which care can be more easily accessed from home. We need to focus on building outward, not inward. Given the cost of treating certain complex medical conditions, hospitals could still house expensive equipment and dispense high-tech treatments, but the emphasis should be on caring for patients at home, not in hospitals.

Health care would benefit greatly from human-centered design, but truly human-centered design is much more than just beautiful architecture. At its core, human-centered design encompasses the responsibility of designing for humanity. We need to stop designing hospitals in isolation and first, answer the question: what is health care? Only once we understand the purpose of what we are designing for can we then decide how to build it. We need to understand the ecosystem — the complex infrastructure of health care — before we can design hospitals.

Thea L. Swenson received a bachelor’s degree in engineering (product design) from Stanford University and a medical degree from the University of Colorado. She is currently a resident in physical medicine and rehabilitation at Vanderbilt University and hopes to specialize in sports medicine.

Illustration by April Brust