Ask a prospective medical student, “Why medicine?” and you will likely hear one of two reasons: 1) to help people and 2) to solve problems. Much of our medical training prepares us to successfully accomplish these exact goals. Therefore, when confronted with a disease presentation riddled with hurdles to achieving these aims — a case that causes us to feel like we are not being helpful, or like we are unable to solve the problem at hand — I have found that physicians oftentimes feel inadequate, and subsequently become defensive.

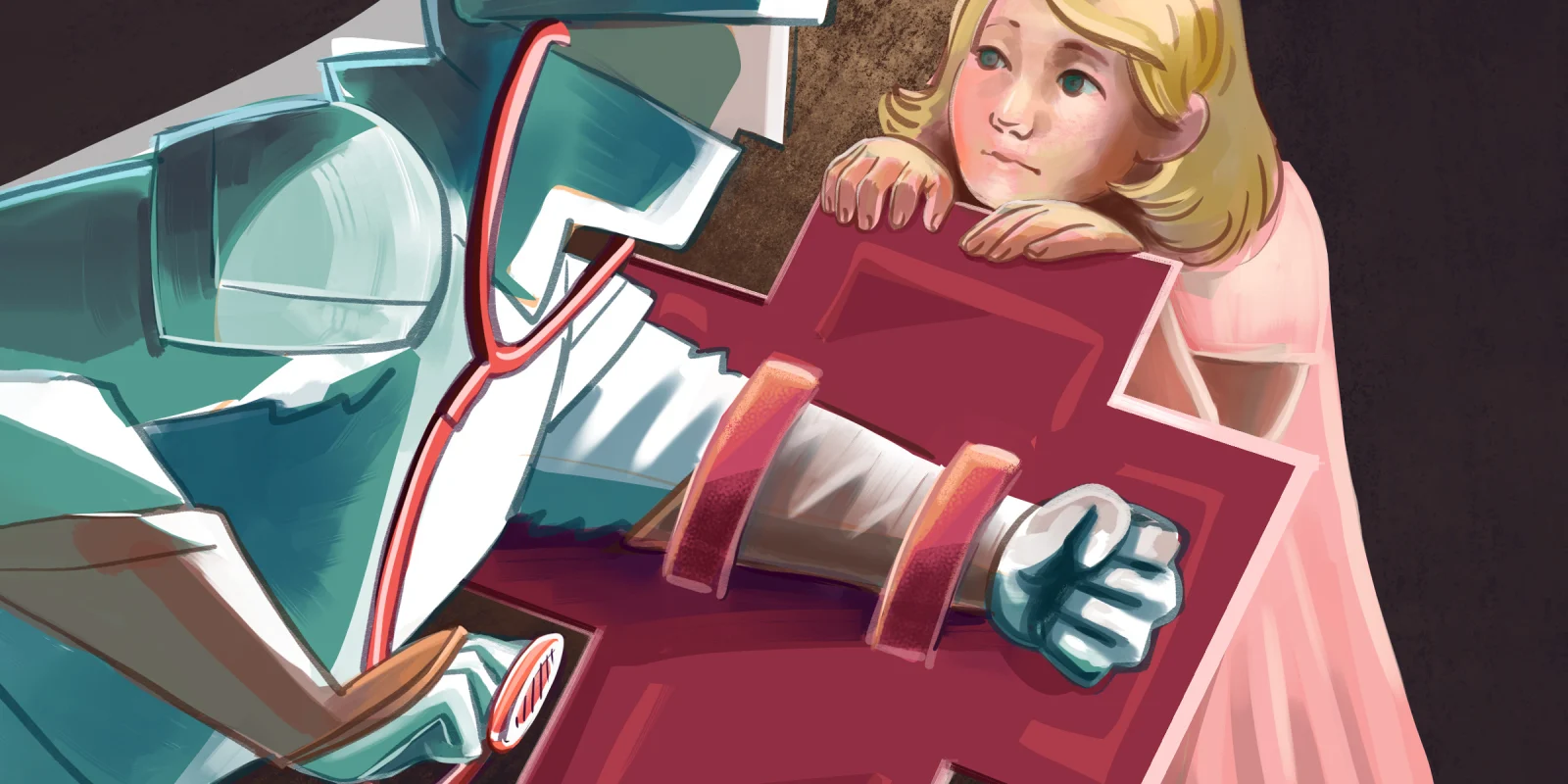

Unfortunately, in many of these situations, physicians oftentimes write the disease off at the expense of truly understanding our patients, waving a gloved hand with the excuse, “It’s just another one of those cases.” Whether a conscious or unconscious decision, this dismissive attitude acts as a defense mechanism against the truth of the matter: modern medicine has not yet figured out exactly how to treat certain diseases effectively. And that admittance of defeat goes against everything we strive toward in medicine. And, as many patients will tell you, there are few diseases that see that gloved hand more often than the disease of chronic pain.

During my time on the adolescent service, I cared for a patient with amplified musculoskeletal pain syndrome who had recently been in a boating accident. She had questionable pancreatitis, but unquestionable acute-on-chronic abdominal and leg pain. Perhaps it is the required SSHADESS (Strengths, School, Home, Activities, Drugs, Emotions, Sexuality, Safety) psychosocial assessment or that we often bare more of ourselves to our adolescent patients in the hopes that they will validate and connect with us, but the nature of this service allows us to develop patient-physician relationships in an expedited manner. I had spent much of my week by her side, gradually learning about her love for swimming and struggles of living with chronic pain.

Throughout her hospitalization, we tried absolutely everything to manage her pain. We attempted medications with different mechanisms of action, scheduled consults with the elusive pain management team, and arranged lavender aromatherapy sticks around her room. Yet she continued to experience symptoms that scored a 10/10 on the pain scale. Through the ineffectiveness of these interventions, we learned that there was nothing we could offer during an inpatient hospitalization to treat her acute-on-chronic pain. Treatment would instead involve intensive outpatient pain rehabilitation therapy consisting of CBT and desensitization techniques. In other words, relief would require a huge investment on the patient’s part — an incredibly unfair ask for a child in pain.

On a dreary Thursday morning after rounds, I went to Room 712 to deliver the news of her imminent discharge. I sat by her bedside, gingerly placing my gloved hand on her forearm as her mother mirrored the action on her other side, and watched as her wide blue eyes widened with each word as I told her that we were doing more harm than benefit by keeping her hospitalized — that it was time to send her home. I helplessly watched as she descended into sheer panic, grasping her chest in an attempt to breathe with tears streaming down her cheeks, and feebly attempted box breathing exercises with her. She cried that I had lied to her. I had told her that while we wouldn’t be able to cure all of her chronic pain during this hospitalization, she would leave with less pain than she had initially arrived in. She cried that I had given up on her, just as she was scared that I would. Just as all of her other doctors had.

Just as all of her other doctors had. I so badly wanted to tell her that I had not given up. I so badly wanted to tell her about the integrative health appointment scheduled for the following day, and the extensive list of potential therapists social work had curated for her. But I didn’t. I couldn’t. She had seen that gloved hand waved by doctors too many times, and it had broken her trust in the health care system, even when we had figured how best to help her.

This is why it is vital for physicians to overcome whatever feelings we have had in the past — feelings of inadequacy in treating enigmatic diseases and fear of the unknown — and validate our patients’ experiences. We must recognize the harm incurred when we do not do so. Otherwise, we risk magnifying the physical and emotional toll that chronic pain takes on our patients by making them feel as though their clinicians — the people they have trusted to have the answers — are not listening. We must fulfill our obligations to the patient-physician relationship, and offer our whole, humble selves, ready to listen and learn — just as our patients so regularly and bravely do.

Dr. Sahr Yazdani is a pediatric resident physician in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She enjoys reading, listening to Pakistani music, and trying out new Thai restaurants with her friends and family! Dr. Yazdani is a 2022–2023 Doximity Op-Med Fellow.

All names and identifying information have been modified to protect patient privacy.

Illustration by April Brust