Just about every specialty has chief complaints that many clinicians dread to see on their schedule. For ENTs, common offenders are tinnitus, globus, and dizziness; for infectious disease, it might be chronic lyme disease; for GI, it may be functional abdominal pain; and the list goes on.

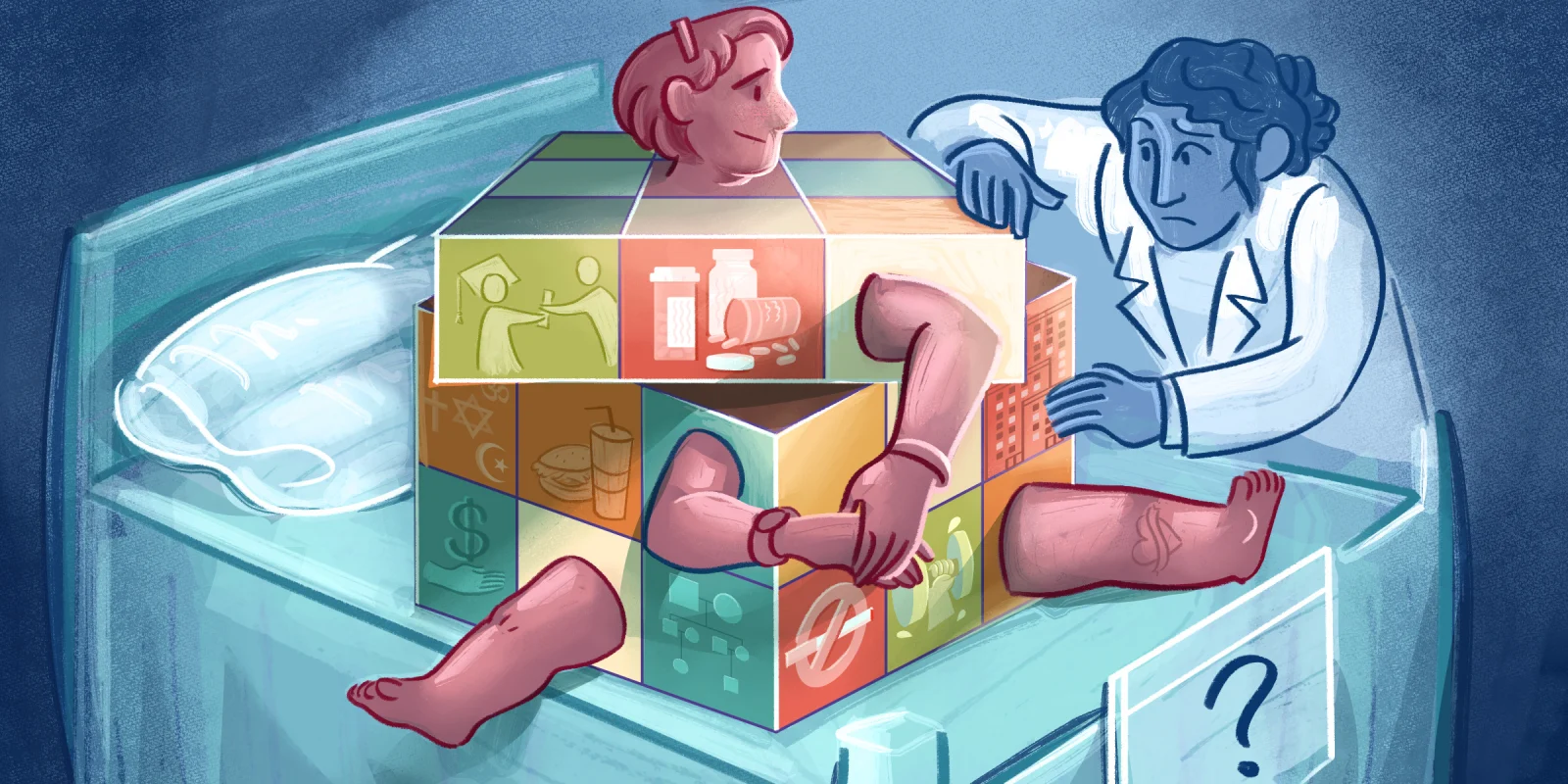

These patients often present with unusual symptoms that do not fit in our textbook boxes of diagnoses. They have often had extensive work ups and tried a dozen or more treatments without much relief. The instinctive response to these patients ranges from skepticism to dismissal and resentment. Why is our automatic response to these patients often so negative?

Speaking for myself, part of the appeal of medicine, and specifically a surgical specialty, is the concrete nature of most diagnoses and the immediacy of the treatment results. If I see a patient with hoarseness and perform a laryngoscopy and find a vocal fold cyst, I can not only provide visual proof of what is causing their symptoms, I also know I can cure them. It is satisfying to solve the mystery. After all, a “whodunnit” is much less interesting when there isn't an answer at the end. When modern diagnostics fail to uncover an identifiable cause, it is easy to blame the patient for their own predicament with adjectives like "crazy," "supratentorial," and "neurotic."

Yet a measure of humility is called for when approaching the limits of our current understanding. History is replete with examples of conditions that were considered "psychogenic" yet were ultimately proven to have an involuntary organic cause. In my field, spasmodic dysphonia (more recently termed laryngeal dystonia) is a condition in which patients develop characteristic voice breaks and strain with certain vowels and consonants. This disease, which affects more women than men, was long thought to be a psychological disorder until the 1960s, when two landmark papers proposed and highlighted the neurologic underpinnings of the disease. Though we still do not know the exact pathway, it is now well accepted as a neurologic disorder with cortical changes found on fMRI studies.

This phenomenon occurs across medical disciplines. For example, ulcerative colitis was previously thought to be psychologically based, as evidenced by article titles such as "Ulcerative Colitis of Psychogenic Origin: A Report of Six Cases," published in 1932, and "Ulcerative Colitis: Studies of Personality," published in 1938, whose author boldly proclaims, "The degree of difference from average individuals was so gross as to make a special control group unnecessary." Although chronic illness can, of course, be correlated with psychological stress and conditions, no one today would claim that ulcerative colitis is due to psychological illness.

Most of us entered medicine with the intention of helping others, of curing them of their ailments. Many of us are type A, goal-oriented, and accustomed to succeeding. When we are confronted with patients with symptoms we cannot explain or with conditions we cannot treat, a mirror is held up to us that reveals us to be imperfect, to be human. This discrepancy between what we are trained to believe we can accomplish for patients and what we can actually do for them can lead to a range of emotions.

The term countertransference is generally used in the context of psychotherapy to describe a therapist’s emotions toward the client, yet I find it is equally applicable to our interactions with medical patients. Perhaps part of why we are so dismissive toward these patients is because they force us to reckon with our own limitations.

Humans are finely attuned to emotions and reactions during conversations, and patients pick up on the subtle shifts in tone and demeanor when we are minimizing their symptoms. Recognizing our instinctive reactions to patients is important to prevent emotion from clouding our clinical expertise. More importantly, maintaining a compassionate response to patients, even when we may have some skepticism about their symptoms, allows us to sustain the therapeutic relationship. I have found that when a complete diagnostic work up is unrevealing, leveling with a patient about what has been tried and the limits of our current medical understanding can be an effective way to maintain the relationship. While empathetic listening and validating suffering may feel insufficient in comparison with a firm diagnosis and treatment, sometimes it can be the most therapeutic medicine we can offer.

Have you had a patient case test the limits of your understanding or capacity as a clinician? Share your experiences below.

Dr. Neelaysh Vukkadala completed his residency in otolaryngology-head and neck surgery at Stanford University and is currently a laryngology fellow at UCLA. He is interested in medical ethics, quality improvement and teaching. He enjoys writing, hiking and landscape photography and can be found on Instagram at @picturesbynv. Dr. Vukkadala was a 2022-2023 Doximity Op-Med Fellow.

Illustration by April Brust