I have recently retired from the practice of medicine after 40 years of caring for patients, a milestone that makes one pause and take stock of what one devoted a career to. During these 40 years, I have been able to watch remarkable advances in medical care, with wonders such as minimally invasive surgery, immunotherapy for cancer, and the development of innovative vaccines that have eliminated some of the childhood infections such as meningitis that used to fill me with terror as an intern.

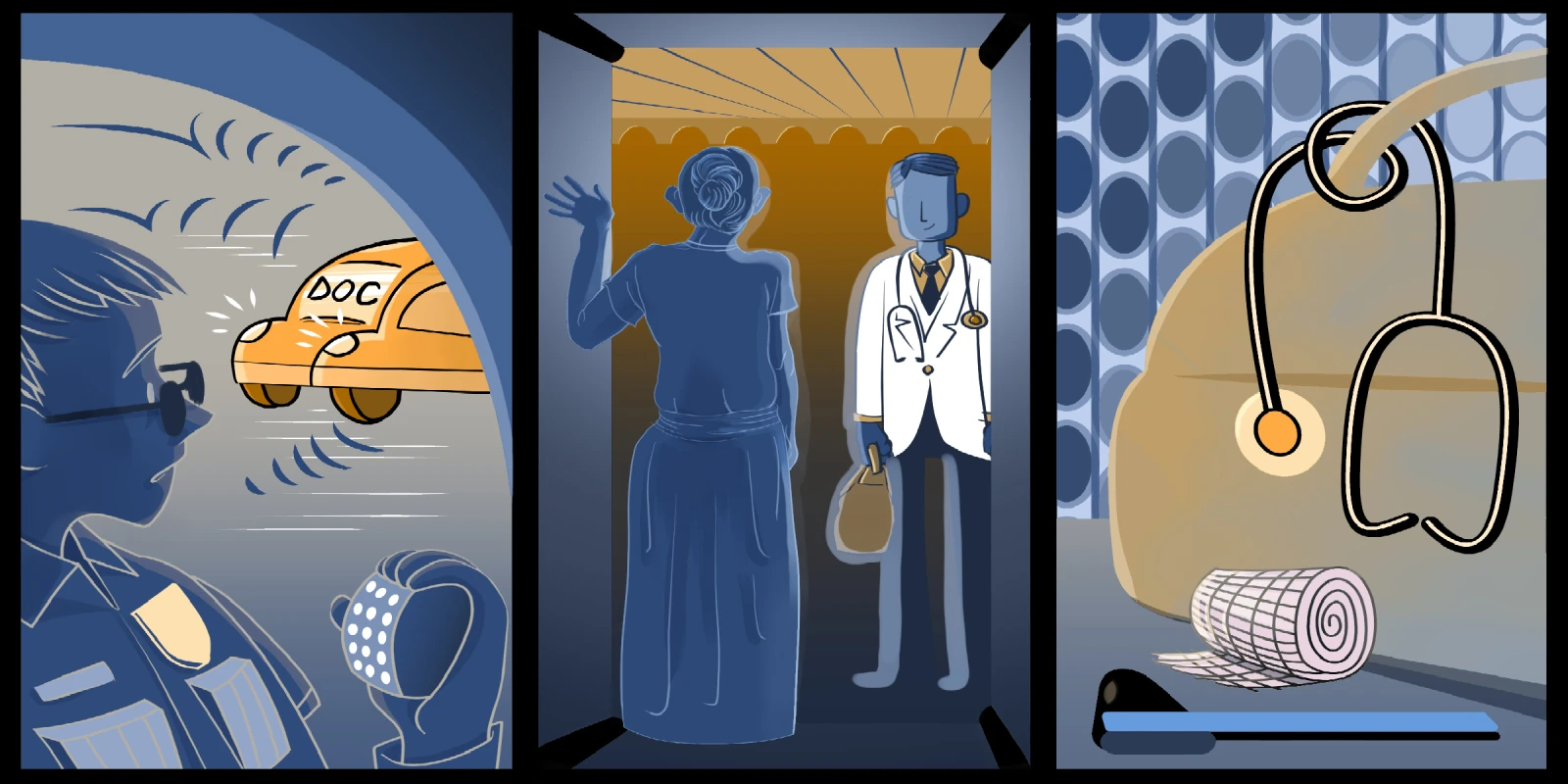

When I first began practice with two of my residency classmates, we cared for patients wherever they needed our help: at the office, the hospital, in nursing homes, or in their own homes. We delivered babies into this world and helped the elderly as they approached the end of their lives. We were following in the footsteps of generations of family physicians who cared for patients from cradle to grave. At the center of medical practice was the act of sitting with a patient, listening to their concerns, examining them with care, thinking about their issues, trying to come to a diagnosis, and devising a helpful plan of action devised for them as individuals. While much has changed for the better in medical practice, the recent corporatization of medicine with its volume-obsessed metrics which pack our schedules have put barriers between patients and their clinicians, threatening the relationships that bind us to our profession.

Well into my career as a primary care doctor, I had an encounter that changed my practice for the better. In February of 2015, after a snowstorm, an elderly woman whom I had cared for for more than 20 years came into the office for a blood pressure check. At age 94, my patient was frail, with severe knee arthritis, and needed a walker to ambulate. She, her son, and her daughter-in-law seemed flustered when I came into the exam room. They described to me how, in order to get from their house to the car on the way to the appointment, they had to lift my elderly patient up by her armpits and — with great difficulty — drag her backward over a snowdrift. I was aghast. I thought to myself, “All this for a blood pressure check”? I decided that from then on she would be having her check-ups at home.

Since that visit, I’ve been keeping my eye out for patients who physically struggle to get to the office and have grown my house call patients to about 20 in number, all of whom are extremely grateful to be seen in their home. I have found that reviving this old-fashioned medical practice — which had been mostly abandoned over the years due to poor reimbursement — gave me the richest of rewards. The privilege of being welcomed into a patient’s home, sitting down together at the kitchen table to share a cup of tea while I inventoried their medications, and seeing the photos of these mostly elderly patients when they were young and strong, gave me a deeper understanding of my patients and brought back the joy of being a doctor.

The fact is, visiting a patient’s home reveals a trove of helpful information. The home visit allows me to understand my patients in a human way and brings to light the barriers they face in their effort to care for themselves in a home where they have lived for decades. The slow pace of a house call, no computer between me and the patient, is so different from the harried, frenetic, computer-clicking pace at the office. House calls allow me to rediscover the sense of purpose and human connection that inspired me to become a doctor so long ago, and learn more about the patient.

We see progress as moving ever-forward and the past as a place that we shouldn’t return to. However, by returning to the longtime traditional role of a physician on a house call, I have recovered a great deal of the joy of being a doctor. The benefits to patients are plain: convenience, reduced travel burden, and attention given to details of their clinical picture that might otherwise be hard to see from within the walls of the clinic. For practitioners, I believe that house calls are a way to rediscover the sense of purpose and human connection that first inspired us to become clinicians.

But the administrators back at the office are worried: house calls are so inefficient! Only one patient an hour? What if the coin counting analysts catch on that every week there are such inefficiencies in our schedules? The beauty of a house call is that we take plenty of time to spend with a patient to listen to them and hear about the challenges they face. I reassure my office manager that the boost in patient and clinician satisfaction is worth the risk of a run in with the spreadsheet crunchers. Besides — if we book them at the end of the day, we might sneak in under their radar.

Clearly, the kinds of human interactions that occur during house calls are a balm for both patients and their doctors. As a teacher, I have several quotes I like to share with medical students, but a favorite is from a 1927 JAMA essay by Frances Peabody: “One of the essential qualities of the clinician is interest in humanity, for the secret to the care of the patient is in caring for the patient.” These teachings lie at the heart of the art of medicine: both listening and caring require time; thus, if we are to preserve the heart of our profession, we must push back against the corporatization that has enveloped our practices and fight for the time to listen to and care for our patients. I can think of no better path to rejuvenating the connection between patients and their healers than the house call.

What are your thoughts on house calls? Share in the comments.

Dr. Good graduated from the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry in 1983, he did his residency in Family Medicine at Middlesex Hospital in Middletown, CT and then worked as a board certified family physician in Middletown, CT for 40 years before retiring in June 2023. Dr. Good continues to teach at the Frank Netter School of Medicine with Quinnipiac University and volunteers as a physician with Health Horizons International in the Dominican Republic.

Illustration by April Brust