Instincts and intuition remain instrumental to decision-making endeavors in almost every situation, including but not limited to, life-threatening circumstances in or out of a hospital environment. My experiences as a practicing physician are not exceptional as I often employ instinct, also referred to as "gut feeling" when vital decisions arise, especially those revolving around the lives of my patients.

Indeed, I have encountered an array of life-threatening instances, where my gut feeling has come handy in delivering sensitive and life-saving decisions and responses. While the gut feeling is often considered irrational, in most cases, my application of such a reaction in the hospital setting has saved many patients. Despite such feelings, I have not been able to save all patients. The health care system has, at times, made it impossible.

During my fourth year of my residency training, I encountered a situation that required a swift response; an initiative should have been pursued without blinking an eye. Unfortunately, the intricacies of this system prevented me from doing so. As usual, I spent the Saturday morning rounding with my team and performing daily required tasks for my patients: discharging patients, following up on labs and images, assuring timely follow-ups, and admitting patients. One admission kept me busy, though.

Miss Jocelyn, a 23-year-old female, presented to the ED, for the first time, with acute onset shortness of breath. She was diagnosed with an acute asthma exacerbation, given the usual steroid and albuterol treatments, and I was called down to admit her under the resident service.

“Just another asthma exacerbation. I’ve done the usual, she hasn’t responded, so I’d like to admit her under your service,” said Dr. X.

I agreed and reviewed her chart. Blood pressure 150/110 mmHg, heart rate 130, respiratory rate 38. “Another 23-year-old, huh? Very young! Why don’t the young ones take care of their health anymore,” I said to myself, as I whizzed down the stairs.

Being a young millennial, she wasn’t always focused on her condition, but rather her iPhone. She spoke to me in short phrases.

“This always happens, Doc,” she said, stopping to take a deep breath.

“I usually go to the other ED across…,” she stopped again to take a big gulp of air.

“The ambulance took me to this one,” stopping again, leaning forward to take another big gulp of air, utilizing her supraclavicular, intercostal and subcostal muscles.

Before she could say another word, I stopped her.

“No worries Jocelyn. We will take good care of you,” I said, as I put my stethoscope on her chest to listen for breath sounds.

I expected to hear scattered wheezing. After all, her admitting diagnosis was acute asthma exacerbation. Instead, I heard none. With every breath, air went in and out smoothly. Perhaps, it was her body habitus, I thought. As I moved down to her posterior chest wall, I heard a few popping sounds.

“Heart failure?” I thought to myself. “Someone so young. How could that be?” I recalled a previous patient who had developed heart failure at a similarly young age due to uncontrolled hypertension. But his examination was clear: bloated abdomen, swollen legs, rales on examination.

Jocelyn, on the other hand, with a BMI of 44, made it very difficult to tell. Pressing on her legs to look for pitting edema, I asked, “Are you on any medication, Jocelyn?”

“Nothing to worry about Doc,” said Jocelyn. "Just do your usual treatment and I’ll be ready to go out tomorrow."

“No, you won’t. Not the way you are going," I thought to myself.

“What medications are you taking? And what other medical problems, besides asthma, do you have, Jocelyn?” I enquired, with a confused look on my face.

“You know, the usual,” replied Jocelyn with an exasperated look as she shifted her focus back onto her phone.

“I am not sure what that means, Jocelyn,” I replied with affirmation. “Have you been diagnosed with asthma? If so, at what age? And have you ever been hospitalized or admitted to the ICU?” I asked adamantly.

Jocelyn rolled her eyes, took another gasp of air, and with a look of anger said, “Go look at my chart, Doc!”

“I did, but unfortunately, this is the first time you are in our ED, and I am unable to access the medical charts from the other hospital,” I replied.

“Code Blue, A6…Code Blue, A6,” I heard on the intercom.

“Shit, I have to go to that,” I blurted out.

Before I sprinted back up, I gave the nurse verbal orders.

“Make the patient NPO. Put the patient on a BiPAP machine. See if we can find a family member to contact. As soon as her labs return, call me or my intern right away. If the patient starts decompensating, call ICU,” I said to the nurse.

“Sure, I will try my best, Doc, but I have nine other patients in the ED that I have to take care of," said the nurse.

“Please do your best, and keep an eye on my patient,”I demanded.

“Yours and everyone else’s,” said the nurse, as I jettisoned out of the ED.

When I finally arrived, catching my breath, the room was chaotic, like any other code blue. Having the gift of a loud voice, I affirmed myself as the team leader. I calmed everyone down and started following the ACLS protocol.

“Start compressions…make sure epinephrine is administered as early as possible…secure the airway…get defibrillator hooked up to the patient…”

This code blue, like many others, affected an elderly patient.

“70-year-old…diabetes…end-stage renal failure…heart failure…sacral wounds…advanced dementia…admitted for pneumonia, no DNR/DNI,” I repeated to myself as I continued with the code. Fifteen minutes in, after several rounds of epinephrine, calcium, bicarbs, and shocks I said, “It's time to call it off.”

“Have we gotten in touch with the family yet,” I asked.

“No, not yet,” said one resident physician.

“OK, keep trying and let them know what happened,” I replied.

“Let’s finish up everything on the electronic death reporting system,” I told the intern.

“8:30 p.m. It's time to sign out," I thought to myself, as I walked out of A6.

I knew I had to get down to the ED and see how Jocelyn was doing. But at the same time, I knew I had to sign out. The night team had already arrived 30 minutes ago. The nurse hadn’t called me nor my intern. I figured everything was OK, and it was time for me to sign out so the night team could take over. Otherwise, I knew I’d be here closer to midnight.

I made the decision to sign out to the night team, emphasizing the importance of following up with Jocelyn in the ED,and mentioning that I believed she might have heart failure.

Before I got ready to walk out, “Rapid response team to…”

“The team will take care of it…today’s been a long day, and I want to get back home. After all it's 9:45 p.m.," I said to myself.

When I returned to work the following Monday, I didn’t get a sign-out on Jocelyn. The new night team wasn’t aware of her. I figured she had been stabilized and discharged.

“Damn, Jocelyn was right,” I thought to myself. She did say we always take care of her and send her out.

Going about yet another chaotic floor day, I thought I’d check up on her chart before I left for the day to see how her hospital course panned out.

“You’re entering a deceased patient's chart,” a window popped up.

“What...did I put the correct name and medical record number?” I thought to myself.

“Yes, I did…this is her…what the hell happened?!” I blurted out, as the other residents gave me confused looks.

I reviewed the chart in detail. That rapid response was for Jocelyn. Her respiratory status had decompensated requiring intubation, which had its own complications, leading to anoxic brain injury and subsequently death. She hadn’t gotten the BiPAP machine on time. The labs hadn’t returned until late. She had come in due to renal failure leading to fluid overload and subsequently respiratory distress. Cause of death: respiratory failure leading to anoxic brain injury and hypertensive renal failure.

Yes, this time my gut instinct was right. But no, this time, it couldn’t save that life. What was the cause? Was it the fact the RN had nine patients in the ED to take care of? The BiPAP machine didn’t get there on time? That other code blue? The fact I had to sign out the patient? Was it me? Should I have followed up on the patient before leaving? Or was it the system with its flaws? My instincts have been instrumental in influencing my judgments in the recent past. I am satisfied that these decisions have been wise, and I have never regretted making one. But what about this time? How many patients have your gut decisions saved and how many have you not been able to save because of this system?

Adil Manzoor is an internal medicine/pediatric physician practicing in New Jersey. He's passionate about mentoring the next generation of leaders. In his free time he writes for local newspapers, mentors youth, reads voraciously, and most important of all, spends time with his wife and their daughter. And when time finally permits, binges Netflix! He can be found on Twitter at @Manzooradil2. Adil is a Doximity 2019-2020 Fellow.

All names and identifying information have been modified to protect patient privacy.

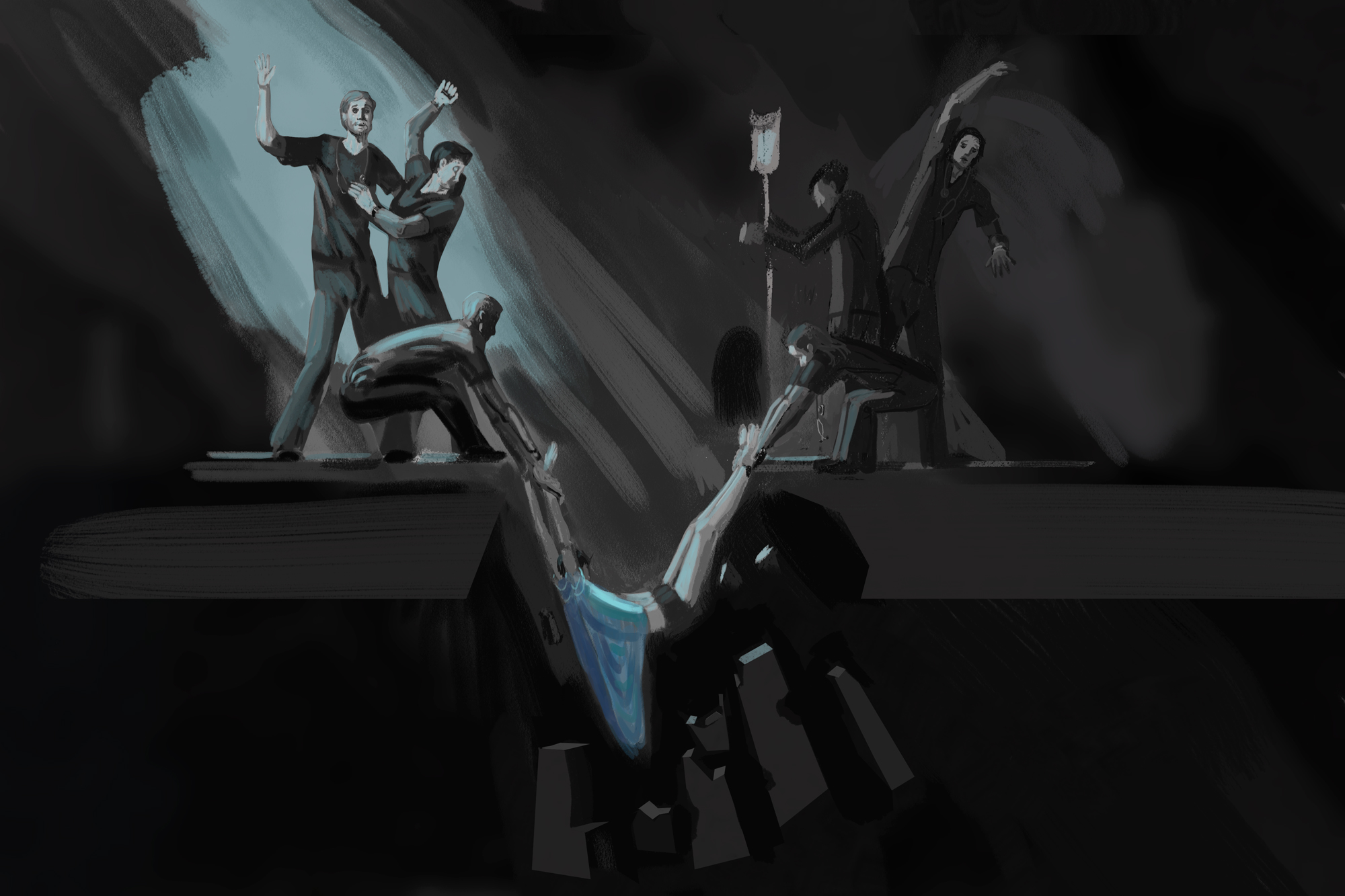

Illustration by Jennifer Bogartz