Victor Ekuta is a 2020–2021 Doximity Research Review Fellow. Nothing in this article is intended nor implied to constitute professional medical advice or endorsement. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views/position of Doximity.

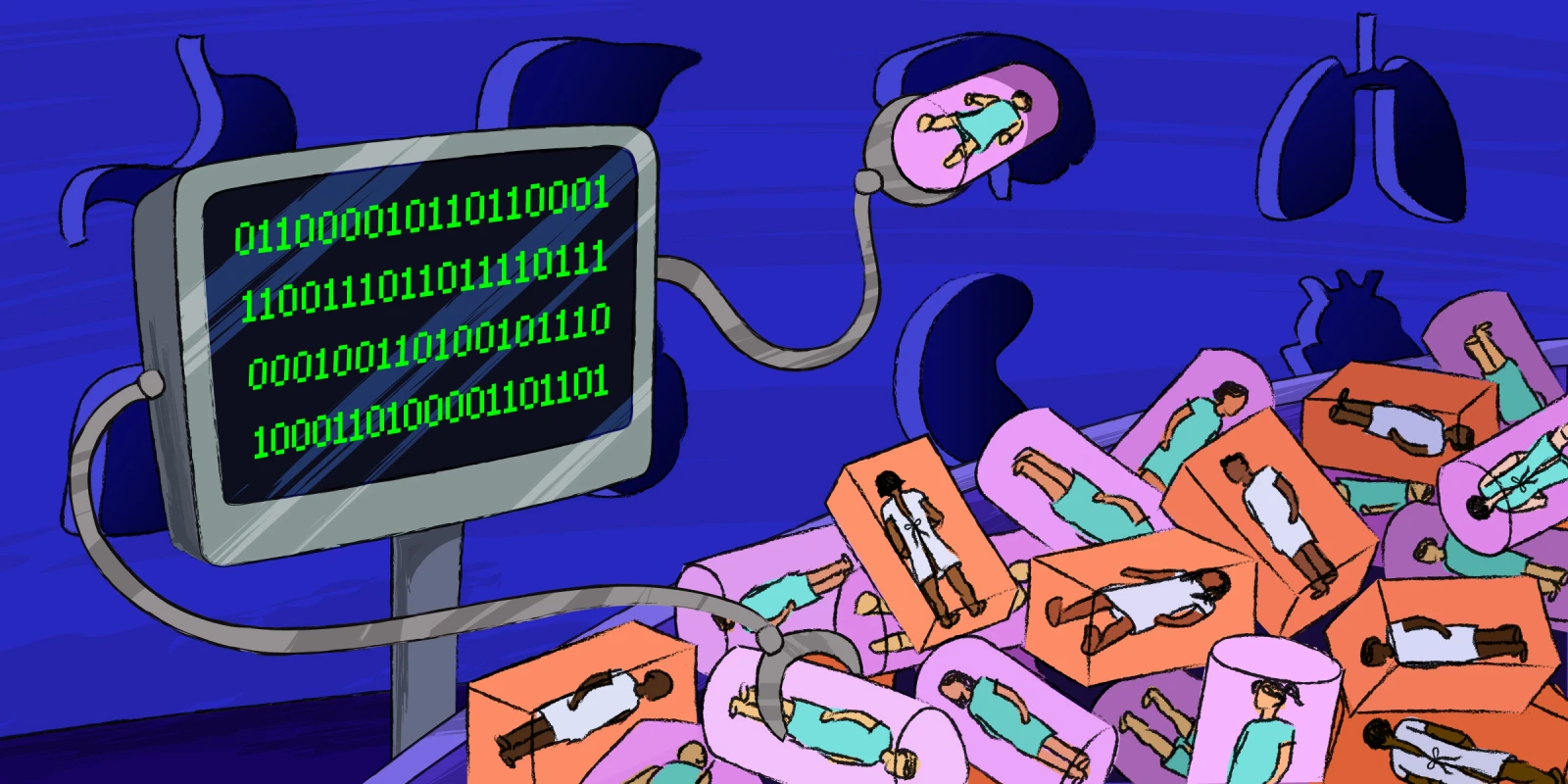

Medical algorithms are increasingly permeating the medical field. Often, physicians rely on these algorithms to make critical decisions about patient diagnoses, treatments, and even life or death. In some instances, these algorithms, which are seemingly designed to be objective, also factor in a patient’s race. But should they?

A recent study highlights the potential ramifications of factoring in race. In the study, Ahmed et al. analyzed the medical records of 57,000 individuals with chronic kidney disease. They found that removing the race multiplier from their estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) calculations for 2,225 African American patients would have resulted in one-third of Black patients being placed into a more severe kidney disease category. More striking, for 64 of these patients, the recalculated scores would have made them eligible for a kidney transplant waitlist. Yet, none of these patients had been referred, evaluated, or waitlisted for a kidney transplant.

Given the pervasive use of race-based algorithms in medical decision-making, additional efforts are sorely needed to understand better how best to incorporate algorithms without codifying health inequalities, something that appears fraught with complications. For example, while removing race from GFR calculations could raise the proportion of Black adults eligible for kidney transplants, it would also disqualify more Black adults from kidney donation. Similarly, even putatively race-neutral algorithms can still have discriminatory effects if they rely on data that reflects societal inequalities. For example, an algorithm that used health costs as a proxy for health needs wrongly concluded that Black patients were healthier than white patients, replicating health care access patterns due to poverty.

Ultimately, Ahmed et al.’s study serves as a cautionary reminder for the use of algorithms in medical decision-making, and underscores the need for more individualized approaches to patients. A medical algorithm or tool should never be used as a substitute for a physician’s expertise or an understanding of the patient’s needs. Moreover, in using algorithms, our responsibility is to ensure that the numbers and variables we feed into our equations reflect the underlying social reality. Racism, not race, is the risk factor for disease. By incorporating this “ground truth,” we can ensure that our algorithms are properly recalibrated to compute for equity.

Victor Ekuta is an MD candidate at UC San Diego School of Medicine. He has previously served as a TEDMED Research Scholar and a Doris Duke Clinical Research Fellow, among many others. In the future, he plans to specialize in academic neurology as a physician-scientist-advocate, employing novel approaches to treat human brain disease, combat health disparities, and boost diversity in STEM.

Illustration by Diana Connolly