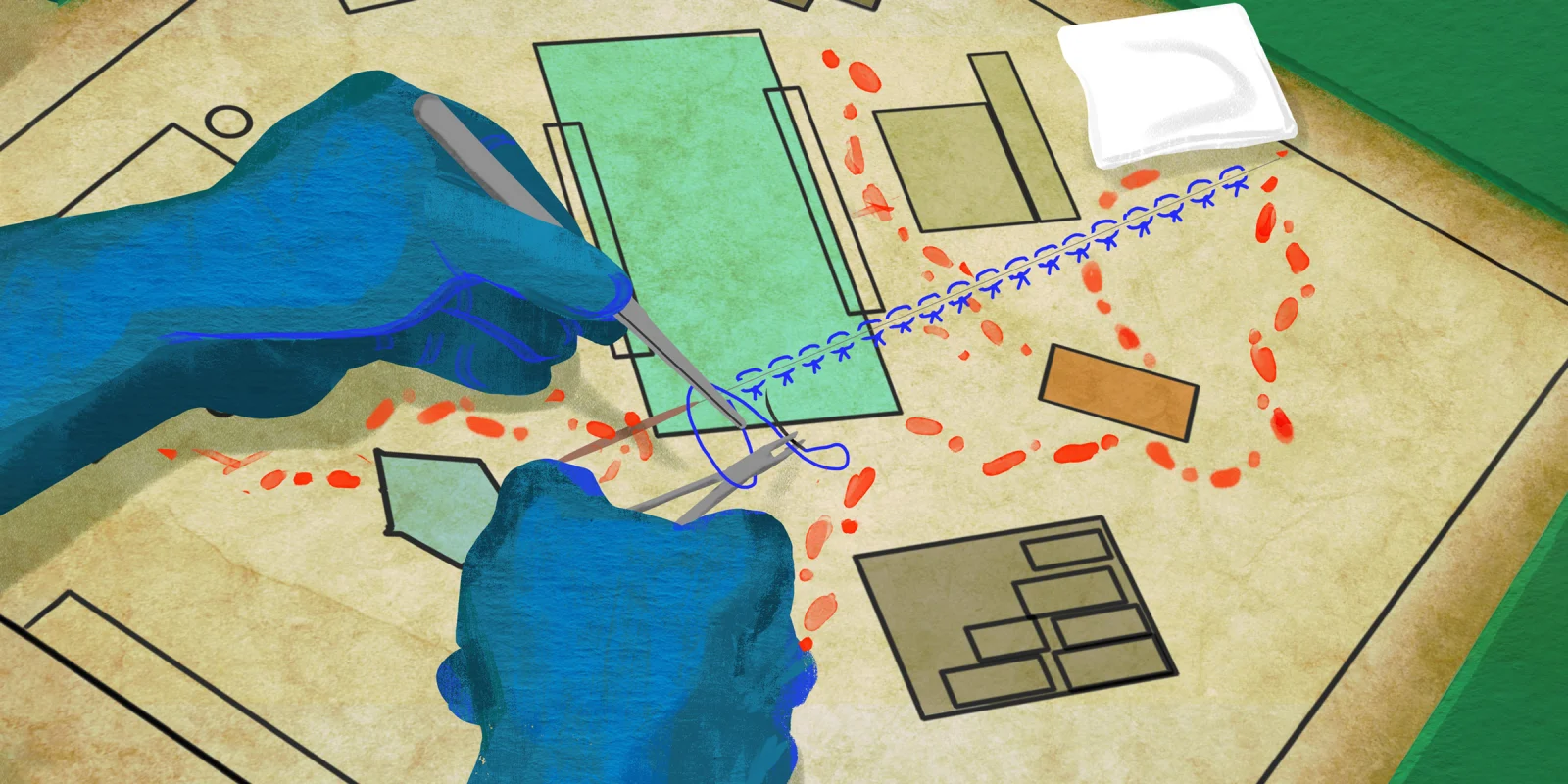

Creativity is an exalted but elusive beast. It can be described as “the ability to produce or use unusual or original ideas.” Creativity derives from the Latin word creare, which means to bring into being, to cause to exist, or to produce. Yet creative thinking can be many things in many contexts. It can be adaptive, innovative, and novel. It is fundamental to how the brain adapts and responds to new information. As someone with a lifelong love for artistic and creative pursuits, I have often wondered during my years of surgical training whether there is room for creativity in surgery, and what encompasses the “art” of surgery.

At first glance, the immediate answer is no — surgery is not and should not be particularly creative. After all, surgery is founded on scientific principles, deliberate practice, and rigorous technique. Creativity and artistic processes are often considered contradictory to methodical and logical thinking, so much so that these cognitive functions are colloquially known as “right or left brain thinking,” a concept that does have some scientific underpinnings. In the context of our working definition of creativity, producing unusual or original ideas in the OR would likely be detrimental in the vast majority of cases. Most procedures have fundamental steps that should be followed in an orderly fashion and repeated in the same way each time to promote success. This was drilled into my head from day one as a surgical intern: "Do it the same way, every time." "Experimental" surgeries can carry a negative connotation and are more often associated with bad outcomes than good ones, except for the rare case where an unusual problem is countered by an unusual approach, and the word “experimental” is replaced with “innovative.”

What, then, makes a surgery innovative rather than experimental? How might creative thinking be used in the OR, where analytical, methodical, and systematic cognitive processes dominate? Adaptive and creative thinking can be used to overcome deviations from the norm or to solve unexpected challenges. In a study examining how surgeons make intraoperative decisions, four decision‐making strategies were discussed, including intuitive (recognition‐primed), rule based, option comparison, and creative. While the authors acknowledged the role of creativity, they explained it is likely to be “infrequently used in high-time pressure, high‐risk surgical situations,” since it requires devising a novel course of action for an unfamiliar situation. This process is neither time efficient nor cognitively sustainable.

Despite this, artistic and creative thinking should not be discounted. Many advances in technique and surgical innovations can be attributed to cognitive flexibility and adaptive problem solving. Improving upon the status quo necessitates trying new things and thinking differently to nurture progress. The rigid structure of the surgical disciplines does not preclude creative thought or imagination. Moreover, despite what I have been taught about repetition as a learning tool, no two surgeries are ever exactly the same, even if the same procedure is performed. In this way, fundamentals are necessary but not sufficient for success. We see this pattern among great artists, chefs, and writers. Even though painting a masterpiece is “artistic” and “creative,” the Old Masters had to rely on fundamental techniques to reach their desired endpoint. Leonardo da Vinci could not have painted "Lady with an Ermine" without knowledge of perspective, color theory, and expert brushwork.

The topics of art and creativity in surgery are discussed with more frequency in certain subspecialties. Most notably, plastic surgeons often cite interest and skill in the arts as a major motivator for selecting the specialty, and much of what is written about this topic can be found in the plastic surgery literature. This is not altogether surprising. Unlike many surgical procedures, the work of plastic surgeons is directly visible to the patient and can place aesthetic considerations at the forefront. Additionally, a major facet of reconstructive surgery involves “closing the defect,” something that can typically be accomplished in numerous ways with good results. This entails immediate problem solving and involves different and more flexible cognitive processes compared to removing the thyroid gland, for example. Nevertheless, creative thinking is certainly not unique to plastic surgery and can be found across medical disciplines, especially when considering the development of major innovations.

One reason I ultimately chose a surgical career was for the ability to work with my hands and create things. While I am privileged and grateful for the opportunity to use my hands every day to heal, I recognize my current state of creating is altogether different then the unstructured days of my youth, where my unfettered mind could make whatever it pleased. Yet I find solace in knowing that my creative mind still has a vital part to play in my role as a physician and surgeon.

When do you think a surgery is creative versus innovative versus experimental? Share your thoughts in the comments.

Dr. Benjamin Ostrander is a current otolaryngology resident at UC San Diego. He loves beach days, long bike rides, cooking elaborate recipes, and playing music. Ben is passionate about art and design, creativity, surgical innovation, and global health. Ben is a 2021–2022 Doximity Op-Med Fellow.

Illustration by Jennifer Bogartz