A Conversation with Bariatric Surgeon Vafa Shayani

When Cancer Research UK warned about the connection between obesity and cancer earlier this spring, they were met with outrage. Frequently and viciously attacked on social media, obese individuals often feel that they are “the last acceptable targets of discrimination,” and now they felt condemned by the medical establishment that was trying to help them.

This isn’t the first time obese patients and medical professionals have clashed. A 2017 Vox article described the ordeal of a patient who was dissatisfied with the results of her lap band surgery. In response to what they considered a one-sided piece, a number of top bariatric surgeons, including Dr. Vafa Shayani, wrote to Doximity and other publications.

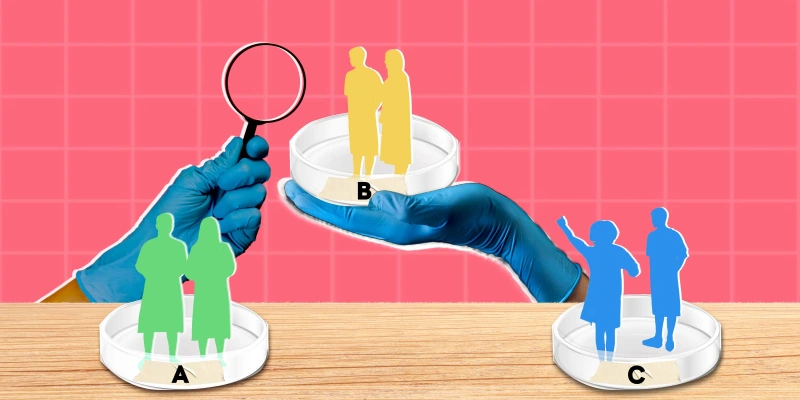

Dr. Shayani says the problem lies in miscommunication and unrealistic expectations on the part of both patients and physicians. Although obesity has been officially acknowledged as a chronic disease since 2008 — one that any single intervention alone cannot cure — people are still looking for a “magic bullet” that will solve their problems. Following on the heels of a Doximity user’s call to action against fat shaming on social media, we asked Dr. Shayani to explain how he helps obese individuals manage their weight and what he thinks other physicians can do.

1. What have you heard from patients or colleagues that makes you think that obesity as a chronic disease is still a controversial notion?

Our biggest challenge with obesity and public perception is preconceived opinions that may or may not be true. People who have never battled obesity blame patients’ battle with weight on their inability to control their desire for food. There is no shortage of scientific data supporting the multifactorial nature of obesity (genetics, metabolic and hormonal factors, psychosocial elements, etc.) But many people still blame patients’ lack of self-control, which makes it difficult for them to express compassion for obese patients.

2. What are other common misconceptions about obesity and obesity treatment?

Here are a couple: A. Obesity surgery/intervention is the easy way out. This couldn’t be further from the truth. Undergoing a major bariatric procedure takes lots of courage and lots of hard work, and no patient should be taunted for their decision to take on this challenge.

B. Obesity surgery will once and for all address an individual’s weight problem. This too is untrue. All weight loss interventions are temporary; bariatric surgery is only less temporary. Without major change in relationship with food, all bariatric procedures will eventually stop working. Most bariatric patients will likely experience weight recidivism after a few years and will require additional bariatric intervention(s).

3. What advice do you have for PCPs caring for obese patients, or for obese patients themselves? At what point does bariatric surgery or other invasive interventions make sense?

Patients with a significant weight challenge (beyond a few pounds) should be referred to a mental health professional to address their unhealthy relationship with food properly and effectively. At the same time, they should be referred to a bariatric interventionist to at least learn about the many options that are available in 2018.

Most patients are able to stick with a non-surgical program for about 3–6 months maximum. During that period, they can lose anywhere from 1–2 pounds per week. This would suggest that many patients might be able to lose up to 50 pounds with significant help and encouragement from the healthcare professionals involved in their lives. Anything beyond that is an unrealistic expectation from a non-interventional program. And for patients who have tried many non-surgical/endoscopic approaches and are reaching a point of frustration, it is only fair to at least discuss with them the more invasive options.

4. How do you counsel patients the first time they are referred to you?

I tell them that just because they are in my office, it doesn’t mean they need to have weight loss surgery. But if they have tried other options and have a lot of weight to lose, I am happy to operate on them and take credit for their success. From there, I tell them about the many options appropriate for their level of obesity and then allow them to ask questions so that they can make an educated decision. I strongly urge them to go home and think about everything and get back to me at a later time.

5. What does it mean for these interventions to “fail”? Why does that happen?

We should make every effort to avoid using the words “fail” and “failure” when it comes to weight loss. Patients are already sensitive about their obesity and have very low self-esteem and to remind some that they have “failed” is really counterproductive. When cancer patients have a recurrence, we don’t tell the patients that chemotherapy “failed.” We simply say that their disease did not respond to a particular treatment and start aggressively looking for alternatives. We should do exactly the same thing for bariatric patients.

There are generally two major reasons for lack of complete response or weight recidivism: 1. The body’s natural response to the surgical procedure; for instance, following gastric bypass or sleeve gastrectomy, the body will do everything it can to overcome the very small size of the newly formed stomach. And ultimately, the body will accomplish exactly that. This is not failure of surgery; this is our bodies having an amazing ability to recover from the insult of surgery.

2. “Compliance fatigue.” This mostly affects patients who have undergone a procedure that requires patient compliance/participation. Adjustable Gastric Banding and Aspiration Therapy are two such procedures. Between the body’s natural fight against anatomic alterations and compliance fatigue, we can pretty much expect all patients, at one point or another, to have to rely on a change in their relationship with food to maintain weight loss. Otherwise, they’ll simply gain the weight back and require additional interventions.

6. You mentioned that it can be hard for bariatric surgeons to accept that obese patients will require future interventions beyond a single surgery. How did you come to accept this? Is there a particular experience that helped you come to this conclusion?

It is not rocket science! We are constantly looking for a magic procedure that does not exist and will never exist. In the 70s and 80s, we offered “stomach stapling” (vertical banded gastroplasty). We ultimately encountered weight recidivism and transitioned to gastric bypass in the 90s and early 2000s. We learned that even gastric bypass does not offer life-long durability, so we were turned on to a much less invasive procedure (adjustable gastric banding), hoping that the reduced invasiveness might be attractive to patients and surgeons. Adjustable Gastric Banding remains a viable procedure, but it does require long-term commitment between the surgeon and the patient, something that both groups struggle with (i.e. “compliance fatigue” on the part of both patients and surgeons).

For the last decade, we have turned to sleeve gastrectomy, which offers more durable results than gastric banding but is much less invasive with much lower incidence of long-term complications when compared to gastric bypass. We are just beginning to acknowledge the limited durability of the gastric sleeve, which has led to frustration from both patients and surgeons. Perhaps the time has come for us to stop looking for the “magic bullet” and instead, start educating the patients, the referring physicians, and the public about the need for a “series of interventions” and not just one operation during the life of an obese patient.

7. What can bariatric surgeons do to help ensure successful outcomes for their patients? What can PCPs do?

Combine bariatric surgery with life-long (if necessary) mental health counseling to help change the patient’s relationship with food. And at the same time, start being honest about the shortcomings of bariatric interventions so that proper expectations for each procedure can be set from the very beginning.

Vafa Shayani, MD is a board certified general surgeon with expertise in bariatric surgery. He is the past President of the Illinois Association of Bariatric Surgeons and currently serves as Co-Chair of the Membership Committee of ASMBS. He has served as a physician leader at several academic and community hospitals and is the past Chairman of Surgery and the current Secretary/Treasurer of Medical Staff at AMITA Bolingbrook Hospital. He has authored and co-authored many manuscripts and book chapters and has served as a principal investigator on several clinical trials.