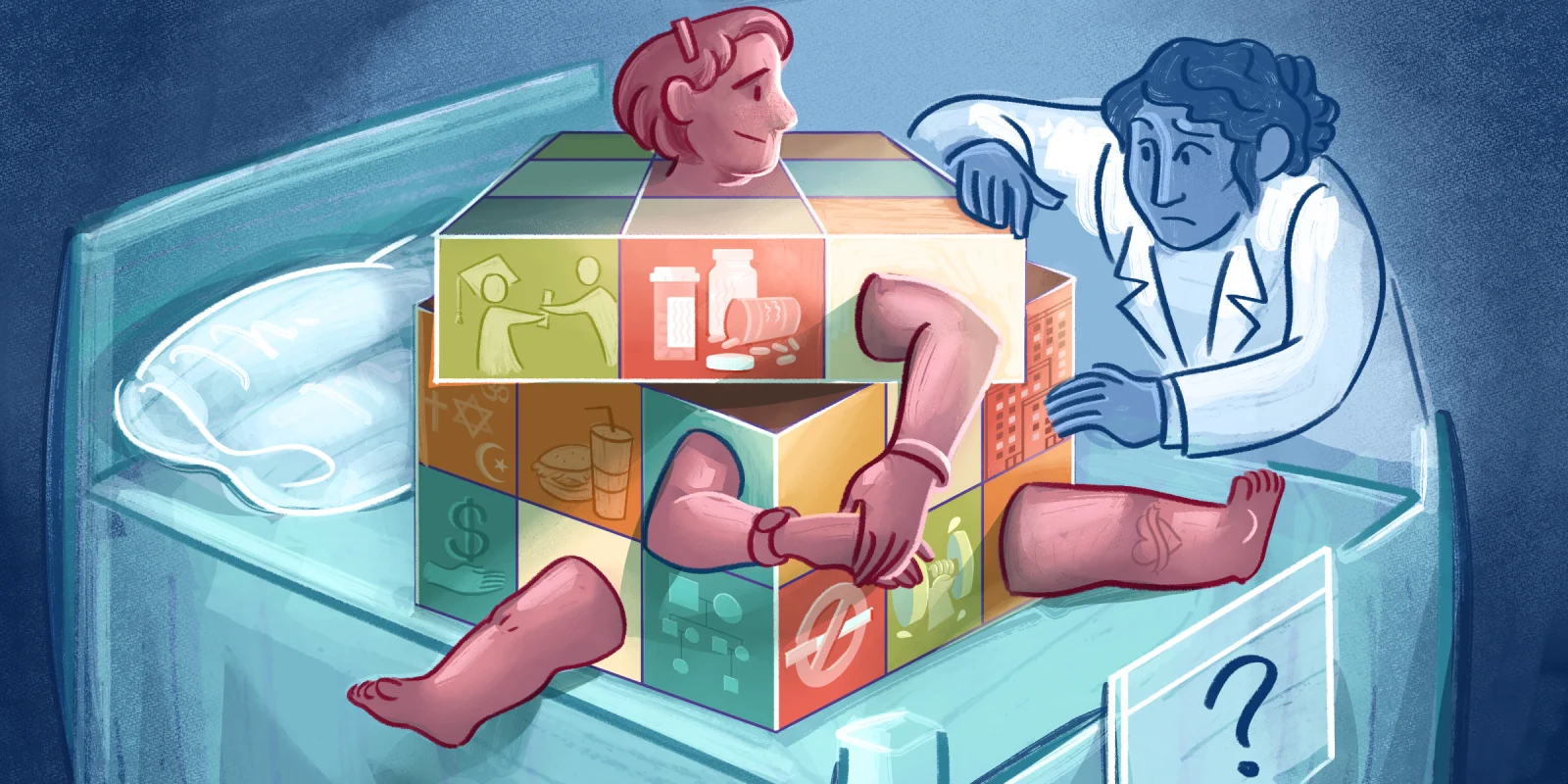

During the course of a surgical career, a surgeon will intermittently come face-to-face with a patient with a mental health problem masquerading as a surgical problem. Frequently, the contentious symptom precipitating surgical referral is chronic pain, although other symptoms such as nausea, loss of appetite, headache, etc., may be manifest. Often, the patient has seen other, sometimes many other, non-surgical physicians prior to the surgical visit. In most cases, the patient has already been submitted to a battery of laboratory tests, CT scans, ultrasounds, and MRIs. Somewhere in the panoply of testing, a tiny kernel of a possible surgical explanation for the chronic pain emerges. The referring physician, typically not a psychiatrist, is initially reluctant to raise the issues of mental health and somatization. The referring physician is much more at ease discussing the relationship between the abnormal (however slight) test result and the patient's symptoms. A stepwise approach to the problem is not misplaced, since it is no small thing for a patient to be considered mentally unwell. Unfortunately, the patient and family can leave this discussion with the impression the surgeon will cure the malady. A clinic visit with a surgeon is arranged.

Every surgeon must encounter such a patient from time to time. Managing the expectations of the patient, the patient's family, and the referring physician requires tact.

A 19-year-old female was referred to my clinic by her family practitioner, Dr. Patel. Over the years, Dr. Patel had been an excellent source of referrals\. He was one of the few physicians to utilize my services when I first came to town. Though we didn't socialize outside of medicine, on the infrequent occasions when I did see him in the staff lounge, we greeted each other enthusiastically and shared the various adventures of our children, who are about the same age. Dr. Patel occupies for me that vague space many would recognize as being less than a close friend but more than just another colleague.

Before I examined the patient Dr. Patel referred, I reviewed the medical record. The patient had abdominal pain, which was thought to be due to gallbladder disease. Her gallbladder ultrasound was normal. The GI medicine consultant obtained a hepatobiliary scan with sincalide challenge. Her gallbladder ejection fraction was 30%. The diagnosis of biliary dyskinesia by that study was barely fulfilled, the standard criteria for diagnosis being an ejection fraction of less than 35% in the setting of appropriate symptoms.

Accompanied by my medical assistant, I entered the examination room. The young lady sat motionless in a chair against the longest wall. Her shoulders slumped, her head inclined forward, her face downcast. She was slim, too slim. Her blond hair flowed across her forehead and shaded her left eye. On either side of her sat a parent who held one of her hands. The patient's hands lay limp in the grasp of her parents. There was an exchange of anxious glances between the parents when I introduced myself. The mood was solemn. The setting in the room was redolent of an early 20th-century seance minus the dim lighting.

Abruptly, the patient pulled her hands away from her parents and snapped, "Why must you hold my hands all the time?"

The mother said soothingly, "Honey, it's because we worry about you. It’s our way of showing you we care."

They all looked at me expectantly, as if I held the solution to what has been an insoluble problem. I asked the usual questions, which revealed an otherwise healthy patient struggling with many months of intermittent abdominal pain and nausea. I motioned my patient over to the exam table. When I got to the abdominal exam, I asked her to point to the area of pain. She brushed her right hand over her epigastrium and left upper abdomen. When I palpated the abdomen, there was tightening of the rectus muscles. On auscultation with my stethoscope, even when pressing firmly, the abdomen remained soft. At this point, I asked the patient to return to the chair between her parents. I was about to imitate Harry Houdini exposing a spiritualist. I chose my next words carefully. I explained that the patient's symptoms and clinical exam were not classic of the diagnosis of biliary dyskinesia and that the abnormality in the gallbladder test was slight. I suggested that what the family perceives to be true — the gallbladder was the problem — was, in fact, false. In short, there might not have been any relationship between the patient's symptoms and her gallbladder.

Physicians are certainly aware of the mantra “to cut is to cure” (or at least palliate — my parenthetical). Yet, however bold the surgeon, enthusiasm must be tempered by the realization that surgical success is exceedingly more likely when the surgical target is well defined. In some ways, the more fulminant the disease, the better.

When a surgeon considers the type of patient I describe, the approach is predictable. The surgeon reviews the record, examines the patient, and sees that the indication for surgery is weak. The link between symptom, chronic pain, and the proposed point of pathology — tenuous. Weighing the facts together, the surgeon concludes the likelihood of a successful surgical outcome when defined as pain relief is small.

Unsurprisingly, in this circumstance, the surgeon will be reluctant to schedule surgery. There are a few options as to how to proceed. They can decline to do the surgery. This has the risk of alienating the referring physician who may wish to be done with a difficult patient. The surgeon can suggest, ever so gently, to the patient and family that perhaps the source of the pain resides elsewhere, and since surgery has risk, this "elsewhere" should be thoroughly investigated before moving forward with the procedure. Ordinarily, this suggestion will be received by both patient and family with skepticism. They were told, after all, by the trusted referring physician that surgery would be curative. However perceived, the suggestion to investigate other causes has the advantage of nudging the family in the direction of insight. The suggestion being, in doctor-speak, that there may be a supratentorial element to the problem.

Lastly, the surgeon may agree to perform the procedure as proposed. If so, the surgeon should be alert to the possibility that any subsequent pain symptoms the patient has could be deemed a consequence of the operation. For this reason, it is essential the surgeon explicitly document, prior to surgery, the discussion of the risks and benefits of treatment with the patient and family. When surgery is performed, in a non-zero percentage of cases, the patient will seem to be cured, perhaps as a result of the placebo effect.

The dilemma for the surgeon is whether or not to operate in these uncomfortable situations. The value of the surgical visit comes from the ability to set the patient and family on the correct path to resolving the patient's problem. Getting there may or may not include performing a surgical procedure. In these situations, candor is the best tool at the surgeon's disposal.

Have you ever found a patient’s condition to be different than originally suspected? Discuss in the comments below.

Dr. Harris is a general and now, acute care, surgeon in a multispecialty group practice with greater than 30 years of experience.

All names and identifying information have been modified to protect patient privacy.

Illustration by April Brust