“I don’t need a palliative care doctor telling me who I should or shouldn’t operate on!”

We were sitting in a conference room discussing challenging patient scenarios on our inpatient service. I was shocked at the angry, dismissive response that came from one of the attending surgeons when I suggested consulting palliative care for poor Alex.

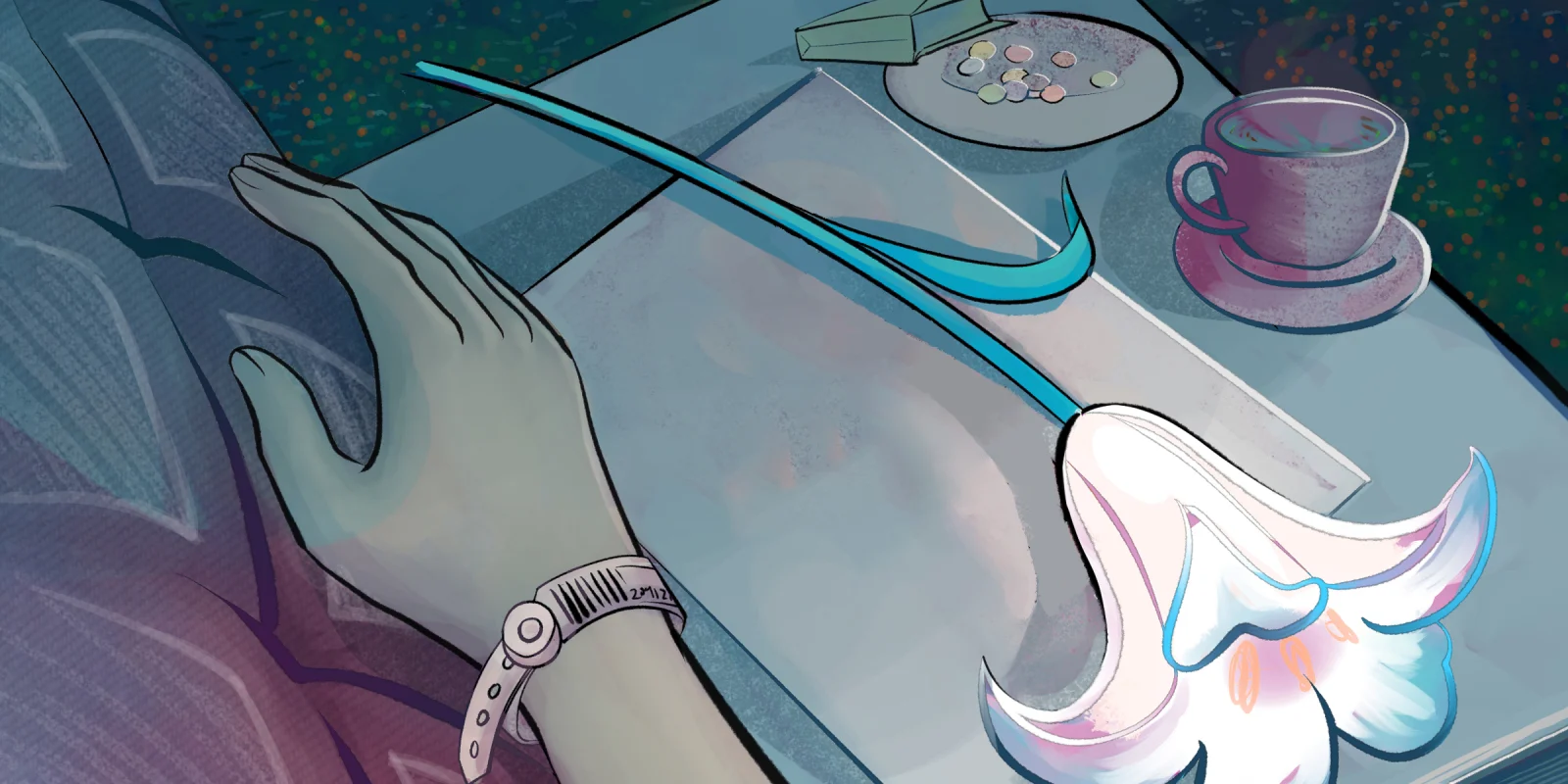

Alex had long, wavy hair and light, kind eyes. He had received a liver transplant as an infant and was neglected by his parents as a child. He struggled with homelessness as a teen. Now he was a high school teacher, full of zest and joy for life, passionate about giving back to others in spite of, or perhaps because of, what had not been given to him.

He also was getting sicker by the day. His transplanted liver was failing him and he needed a new one to survive. Unfortunately, he was diagnosed with a complex infection preventing him from receiving a new liver straight away. Despite our attempts to help him combat the infection, it was not getting better.

Without a new liver he would definitely die. The final option to try to clear his infection was to take him to the OR for an abdominal exploration, which no one felt optimistic about given his prior surgical history.

“I’m not suggesting that…” I replied meekly after the unexpected outburst. “I just think it would be helpful to have a goals of care conversation with him since he doesn’t have much support and this is such a complex issue…”

“So you think we should just let him die?” piped up another surgeon.

I fell silent. I was exasperated. Seeing Alex’s face every day on rounds and having to talk shop with him about the plan for the day, while knowing in my heart that the overall prognosis was not good, felt terrible. It felt wrong to look at his smiling face and tell him what antibiotics and drains we were trying that day and not tell him that the prognosis looked poor or that we should discuss the possibility of end of life approaching and his wishes. I was frustrated and angry that the other surgeons couldn’t see how palliative care in this situation would be so incredibly helpful not just for Alex, but for us, as his surgeons, to see what perhaps some of our eyes were blinded to: the limits of what our hands could do to help this poor young man.

One of the biggest barriers to delivering palliative care to sick surgical patients is navigating as a surgeon when you have reached your limits of what you can and/or should offer, and discussing this honestly and early on with patients. I have heard some surgeons refer to the concept of palliative care as “giving up on patients.” Based on my attempted advocacy for palliative care support for Alex, it seemed like other surgeons viewed palliative care as allowing patients to die, or as giving away the right to decide to operate to another group of physicians. What we fail to remember sometimes is that while the right to operate may lie with the surgeon, the right to be operated on lies with the patient, first and foremost. Ultimately that is the right that matters most.

The day he was taken to the OR to attempt to clear his infection, an even larger problem was found. After the operation I noticed a change in the other surgeons’ demeanors. Now that it was abundantly clear that he would not clear this infection to get another transplant, and therefore that he would die soon, those who initially lashed out at the idea of palliative care nodded silently when I suggested involving them again. Now that the hope was extinguished, it felt like their walls came down. I just couldn’t understand why it had to get to that point to admit that we should be discussing his goals of care and the possibility of end of life in the absence of a clear path to a new liver transplant.

Surgery and palliative care are often viewed as opposing forces. As surgeons we pride ourselves in taking action, being goal-oriented, and achieving concrete results to improve our patients’ health. Many of us enter the field because of the instant gratification obtained from seeing a patient with a diagnosis, performing an operation, and having the privilege of watching them improve after the surgery.

Unfortunately, there are many instances where patients cannot physically tolerate the surgery that they need or where surgery will not bring about the long term intended goal that they desire. Alex wanted to live a long, healthy life and was open to having more surgery, but performing the surgery that he needed (repeat liver transplants) was not a viable option.

In recent years, there has been increased interest in surgical palliative care, both as an area of clinical expertise that can achieve more goal-concordant care for complex surgical patients, as well as an important field of research and education. Palliative care in the context of surgery includes having discussions of when to operate and when not to operate when patients are seriously ill or nearing the end of their life. Doing an operation often sounds to patients, families, and even other clinicians as a simple solution to fix a complex problem, but oftentimes it causes worse problems or prolongs a patient’s end-of-life in ways that are not meaningful and potentially more traumatic and painful. In extreme cases, operating can mean the difference between a patient dying comfortably with their loved ones at their bedside versus dying alone in a sterile OR.

The effort to destigmatize the concept of palliative care among surgeons is an important one. Integrating palliative care education into surgical training equips surgeons with tools needed to provide holistic care for patients, even when surgery is not an option. Surgical trainees report inadequate training in palliative care; however, there have been increased efforts at researching and addressing this education gap, with promising results. Residents and fellows who are provided with palliative care curriculum topics report increased comfort with having end-of-life conversations with patients, among other outcomes.

After his surgery, I told Alex that the infection could not be controlled and therefore he could not get a transplant, which meant that he was going to die, likely on the order of days to weeks. He cried, and I cried with him. He told me he wanted to die with his chosen family by his side, since he could not physically travel back home.

It took me a while to stop internalizing his death as a failure on our part as his doctors and surgeons. It was humbling taking care of Alex, and actually facing the limits of what we could do for him as surgeons. Ultimately, I think the most important thing we did for Alex was clarify his goals and wishes for the end of his life, and try to make them happen for him.

I had the privilege of meeting his loving chosen family who all traveled from out of state to be by his side as he left this world. They shared stories about how he loved playing board games, how much his high school students that he taught adored him, and how he was always the one in the group to make others smile and feel good. The love in the room was abundant and palpable, and it lingered long after he took his last breath.

How do you think surgeons should approach palliative care? Share in the comments.

Dr. Mohini (Mo) Dasari is a general surgeon in Kirkland, WA. She practices and teaches yoga, writes for pleasure, therapy and advocacy, and loves posting her amateur cooking and baking on Instagram @modalala. Her favorite thing to do is spend quality time with her husband, two-year-old daughter, and seven-pound dog. She tweets at @mdmdaware. Dr. Dasari is a 2023–2024 Doximity Op-Med Fellow. All names and identifying information have been modified to protect patient privacy.

Illustration by April Brust