Less than a year ago, I heard Ben Stiller on the airwaves, doling out kudos to his heroic doctor, who had diagnosed him with early stage prostate cancer by using a simple, widespread screen.

What was interesting in that particular instance was that Stiller was actually underage. What I mean is that the star was not of age to be screened, according to current prostate cancer screening guidelines (American Cancer Association’s guidelines). He was in his mid-forties.

The guidelines are pretty straightforward. Men over the age of 50 can be screened, if they choose to be, after an informed consent discussion with their physician, outlining risks versus benefits. Men of African American descent or with first-degree relative with prostate cancer are to start at an earlier age, often 40 or 45.

But, interestingly, Stiller didn’t qualify for either of these two categories. His doctor may have acted outside of guideline parameters, but he became an instant hero. And he was indeed a hero, in a way. He was thinking outside the box.

But if thinking outside the box translates into screening patients blindly, and outside of guideline parameters, then why follow any of these parameters at all? Couldn’t we all be extra thoughtful as physicians and offer the screen extra early?

Stiller’s miraculous diagnosis brings into the limelight this dilemma, faced by practitioners everywhere, when considering patient screens: What the guidelines say versus what we want to do to satisfy patients. When our hearts want patients both healthy and happy, it could translate into tweaking the parameters, or the way in which we interpret them. Think of it as VIP treatment. Getting an early screen — the equivalent of backstage passes to a show because, well, you know someone. But what if I consider all of my patients VIP? Because I do — I want to save them all. That’s when I’m in a bind. Did Stiller’s physician do it because of the fame? Or because he screens every single patient earlier than recommended?

We often face this question. A patient who asks to “screen for every type of cancer, regardless of risk factors, regardless of age.” And I understand where they’re coming from — they’re equating diagnosis with increased longevity. But this often puts us, as practitioners, in difficult spot, because we know that’s not always the case. And when completely not indicated (think Ca-125 or CEA, tested randomly), it can be hard to say no. I’d even go further and bet that denials of these specific requests are proportional to negative patient reviews.

So how does one approach such predicaments?

By adhering to guidelines, that’s how. Because they provide just that — a guide. When we practice academically, we’re following rules, set out by years of scientific research and backing. Otherwise, how would one know when to screen? Yearly? Monthly? Or — and brace yourselves at this one — at the patient’s discretion? Heck, I’d consider screening at birth, if I could, and if it meant longer survivals for patients. I’d take it a step further, if I could- why not screen in utero? (I say this tongue-in-cheek, of course, for added drama, but also to make a point. I do also realize there actually are in-utero screens, but those typically make sense!).

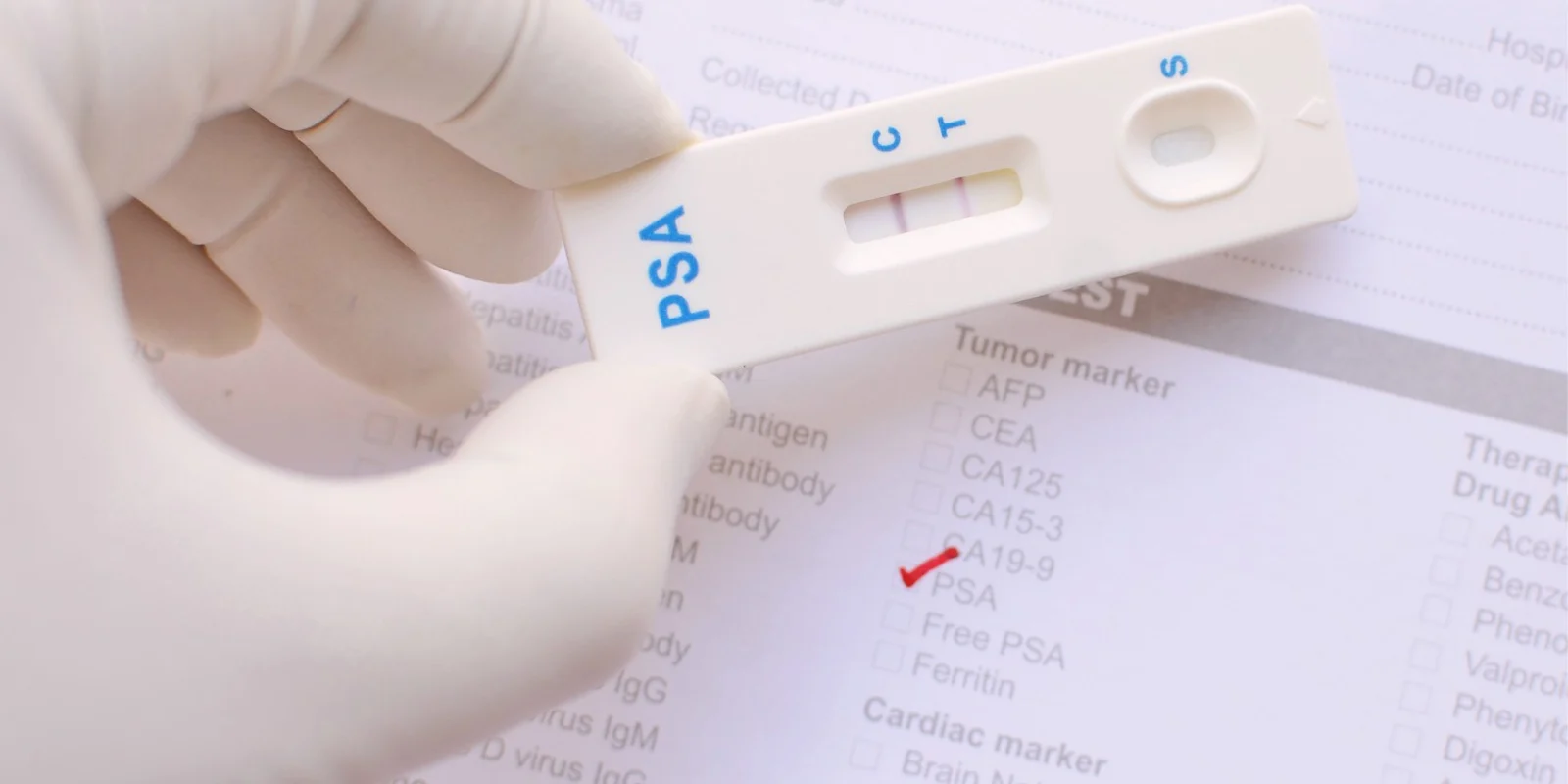

The screen specific to prostate cancer is indeed a simple one: a blood test called PSA, or Prostate Specific Antigen. While not perfect, it’s relatively effortless, and typically performed at one’s annual. The needle goes in and — chop, chop — the test is over.

Stiller said yes to this particular screen. But what surprised me about his case was, again, that the screen had been offered in the first place. It seems that his doctor may have had a sixth sense of sorts, I’m thinking, because Stiller says, “What I had — and I’m healthy today because of it — was a thoughtful internist who felt like I was around the age to start checking my PSA level, and discussed it with me.”

I don’t take issue with Stiller’s message. What I don’t quite agree with is the wording of it — it serves, in a way, to frighten; to send fans out reflexively, even blindly, in search of this magic screen. And, although it’s a powerful one, it’s not as miraculous as it seems. None of the specifics are discussed, not even the negatives behind it. For example, did you know that less than one in three men with an elevated screen turn out to have prostate cancer? I won’t even mention to size of the needle used to biopsy the prostate, or the route taken to insert it (the prostate can be reached through the rectal area), nor the pain.

Another crucial point: I refuse to believe that an accurate gauge of the ‘thoughtfulness’ of a physician is whether or not they ‘feel’ like performing a screen. A screen, by nature of that term, means no symptoms warrant the test. The age at which it’s performed is determined by factors like age, risks, and exposures. Thankfully, we’re practicing in a modern age of medicine, and no longer have to ‘feel’ when it’s right to perform these tests — mainly because we follow guidelines derived from standardized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. And thank goodness for these advances.

You can view it as ‘mincing words’ on my part, but I like medical messages that are clearly conveyed, without cause for confusion or panic. I think it’s an important part of delivering them to an audience because they are so often misconstrued. But I also get that it’s difficult to always get them right, especially in speaking engagements, when on the spot and off the cuff.

Despite it all, at the end of the day, Stiller did get it right because he increased awareness, and I commend him for that. It’s the perfect opportunity to call out other voices — the real voices in medicine — so that more of us can spread these positive messages, and in the right way.

Dana Corriel, MD, is a board-certified internist, who heads the clinic at Pearl River Internal Medicine. She also serves as the Director of Quality for Highland Medical, PC. When Dr. Corriel is not ‘doctoring’, she is a mother to three rambunctious boys. In her spare time, she enjoys crafting commentaries on her website, as well as initiating discussion on social media that are central to the field of medicine. Her goal is to humanize the face of medicine.