In the season between the emotional turmoil of Match week and the day our new interns started their first day, they’ve navigated the challenges of moving to a new city, celebrated medical school graduation, and of course, have been working hard during their first few rotations of residency. These ex-MS4s have certainly had a lot to navigate over the past few months, and while the first few rotations may have put some new interns’ minds at ease, for others, it may have made the task of succeeding in residency seem all that much more intimidating. However, in addition to the four years of hard studying, long clinical hours, and exams in medical school (not to mention college), most new PGY1s may be relieved to learn that there are likely hundreds of skills they already possess that will set them up for success in the coming year and beyond.

Skillset 1) Grit, Stamina, and Sacrifice

In the 2004 movie “Miracle,” coach Herb Brooks famously makes the 1980 U.S. Men’s Olympic Hockey Team perform sprints on the ice ad infinitum. The players become visibly exhausted as the scene goes on, practically crawling to the edge of the ice each time the coach blows his whistle and yells “Again!” The movie makes it clear that Coach Brooks was using the exercise to get his players to recognize that their team was bigger than themselves, and I think most athletes who watch this scene can remember a time when we felt like we couldn’t take another step, and somehow found the strength to sprint across the ice yet again.

I found most of my path to residency to be not unlike my experiences as an athlete, except the fatigue came with brain fog and hundreds of practice questions rather than sprints. I traded nights of practicing soccer drills in the backyard for days of practicing hundreds of surgical knots, and instead of a week of “two-a-days,'' I've powered through rounding on 30 patients while post-call.

Many of us have encountered someone like Coach Brooks. Whether it was a tough teacher, research mentor, or a strict ballet instructor, they taught us to keep working to get better — even when we were exhausted. We set alarms to wake up early, and took pride in the victories, the new skills, and the personal records we achieved as a result of sacrificing our own comfort and free time. I’ve also found most of my “tough attendings” (much like “tough coaches”) weren’t unreasonable at all. They just had an unwavering standard and pushed students to meet them there.

Skillset 2) The Patience and Understanding of Customer Service

One wouldn’t think that summers spent making ice cream cakes, bagging groceries, or delivering items for Postmates have much to do with being a doctor, but like any other job that requires interpersonal communication, I’ve found that customer service experience has been invaluable as a resident. During summer jobs, I learned to let rude comments wash over me and appease customers who complained that their ice cream was “too cold.” People who were stressed, tired, or anxious used to take these feelings out on me in the face of inconveniences, and the hospital only amplifies this dynamic. It’s difficult to work long hours and bear the brunt of inappropriate demands and unrealistic expectations; it’s even trickier when there are sick people waiting to be seen in the ER rather than waiting in line for ice cream.

Of course, the burden should never be on an individual’s resilience or interpersonal skills to overcome a toxic or unsafe work environment. This is meant not as a skillset for overcoming systemic issues, but a tool for necessary management of complex emotional situations with patients, families, and even other clinicians. As a junior resident especially, most people spend a lot of time fielding pages and calls from nurses, consultants, family members, and patients. There is an art and a science in the practice of medicine, and these customer service skills come in handy more times than one might think.

Skillset 3) Feeling Comfortable Failing At First

During my second year of medical school, a friend (who is now an orthopaedic surgery resident) taught me how to kiteboard. During a warm spring day, she skimmed across the waves as the wind dragged the kite, making it look effortless. I had a decidedly more frustrating experience. I spent a good portion of the morning chasing after the training kite on the beach, unable to even keep it in the air. It finally clicked by the afternoon and I was able to join her in the water, but as we were driving home, I lamented at how bad I had been at it. “That’s the only way to get good at things though! You just have to get that frustrating part over with,” my friend replied.

It had been awhile since I’d tried to learn a brand new skill, and the morning had been humbling, sweaty, and unsatisfying. In a field like medicine where high-achieving students are put in a competitive environment, there is a lot of pressure to give off an air of confidence, success, and unflappability at all times. But residency has a steep learning curve and many interns may find themselves trying to very quickly learn dozens of new skills. It is critically important that trainees are able to train in an environment where it’s “OK” to be a learner, to ask questions, to admit when we’re wrong and ask for help. While this may or may not be the case at every training program, the experience of successfully working through difficulty is important. Working through the awkward early learning phases is easier said than done for most medical students, but my friend had a point: All paths to being an expert at something start with this tedious first step.

Skillset 4) Caring For, Listening To, and Helping Another Human

One of the most interesting things about being a physician is that by working with people during critical times of their lives, we can’t fully separate our work from the very experience of being human. Experiences with illness, injury, and death are often what drew me and my colleagues to this profession in the first place, and these are experiences that new residents can draw on to help their patients now. I’ve thankfully never been a surgical patient myself, but I know several friends who have been in this position of being a physician-patient. A friend who had achalasia and required multiple surgeries during our third year of medical school told me that her week spent in the hospital bed taught her more about how to be a good doctor than months standing next to it on rounds did.

Similarly, the summer one of my best friends was killed in an accident unexpectedly was a terrible, grief-filled blur, but it’s an experience that helps me understand and help my trauma patients and their families. I’ve been the person on the other end of the late night phone call, and I remember that feeling every time I take a deep breath and dial a family member’s number from an ICU phone.

By the end of my first week of intern year, everything I had been afraid of had already happened. I’d had to call an attending in from their home to ex lap someone in the middle of the night. I’d had to respond to a code and send someone to the ICU, and I’d had to break a fatal diagnosis to someone in a dimly lit ED room at 3 a.m. I didn’t know the best way to handle any of these situations, and will likely always strive to get better at them. There are, of course, techniques that have been taught in medical curricula to break bad news or deal with complex situations, and these are important principles to follow. However, the skills new interns have built from a lifetime of listening to friends who have had a bad day, caring for a family member during a tough time, or helping a stranger in need are immensely valuable as well.

Skillset 5) Cultural Humility, Community, and Connection

Something that makes medicine incredibly interesting but also immensely complex is the cross section of humanity that we see within the walls of the hospital. In a single afternoon in the clinic, I might see an adult with a developmental delay and his caretaker, a refugee who requires an interpreter, a prisoner escorted to the clinic in shackles, and a teenager in the foster care system and her social worker. Even before medical school, many incoming residents have sought out opportunities to meet people unlike themselves. A medical school classmate worked for the Peace Corps in Guatemala and saved the day on rounds when we were unable to find a K’iche’ interpreter for a patient. Several resident colleagues work in global surgery and travel to learn from and collaborate with surgeons all across the world.

It’s important to appreciate how profoundly different other people’s experiences have been from our own, or sometimes, how similar. I taught yoga at an inpatient addiction and substance abuse rehabilitation center when I lived in New Orleans. Several women came to class regularly and I had a chance to learn about the parts of their lives that happened before they had been consumed by their illness. I would hear stories of lives that were similar to mine, a reminder of how very little separates us, and how complex any one person’s experience with health and illness is. Nearly a quarter of my medical school class pursued a master’s degree in public health during medical school. We explored how environmental factors, health policy decisions, cultural norms, systemic racism, food insecurity, education, etc., impacted the health of our patients every day. The skills incoming residents have built by seeking to understand these social determinants of health, to meet people of different backgrounds, and to give back to communities are so integral to being in medicine. Not only is it important in caring for patients, but understanding all that affects their health outside of the four walls of the hospital as well.

There is a seemingly infinite amount of information one needs to learn to practice medicine, and in a system that reveres standardized testing and didactic learning, it can feel overwhelming to see the thousands of unread pages of Sabiston’s Textbook of Surgery sitting on your desk. Residency is meant to be a time for learning, and working through this textbook and taking care of patients 80 hours a week for 50-plus weeks a year will give residents the opportunity to acquire and hone this knowledge. But for overwhelmed new interns, nervous MS4s, or anyone else who has been in these shoes, it’s important to remember that the practice of medicine involves interacting intimately with life and humanity, and perhaps our lived experiences set us up for success more than we know.

What skills did you not learn in medical school? Share below.

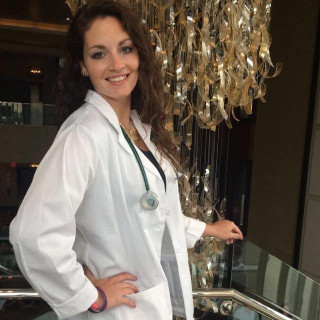

Colleen is currently a general surgery resident in Salt Lake City, UT. She hopes to pursue a career in academic surgery where she can continue teaching, writing, and research in addition to clinical practice. She has an MD/MPH from Tulane University in New Orleans, LA, and hopes to continue to use public health principles to improve surgical outcomes for patients. In her very extensive free time as a surgery resident, Colleen enjoys art, skiing and snowboarding, hiking, writing, dancing, and practicing yoga. Colleen is a 2021–2022 Doximity Op-Med Fellow.

Illustration by April Brust