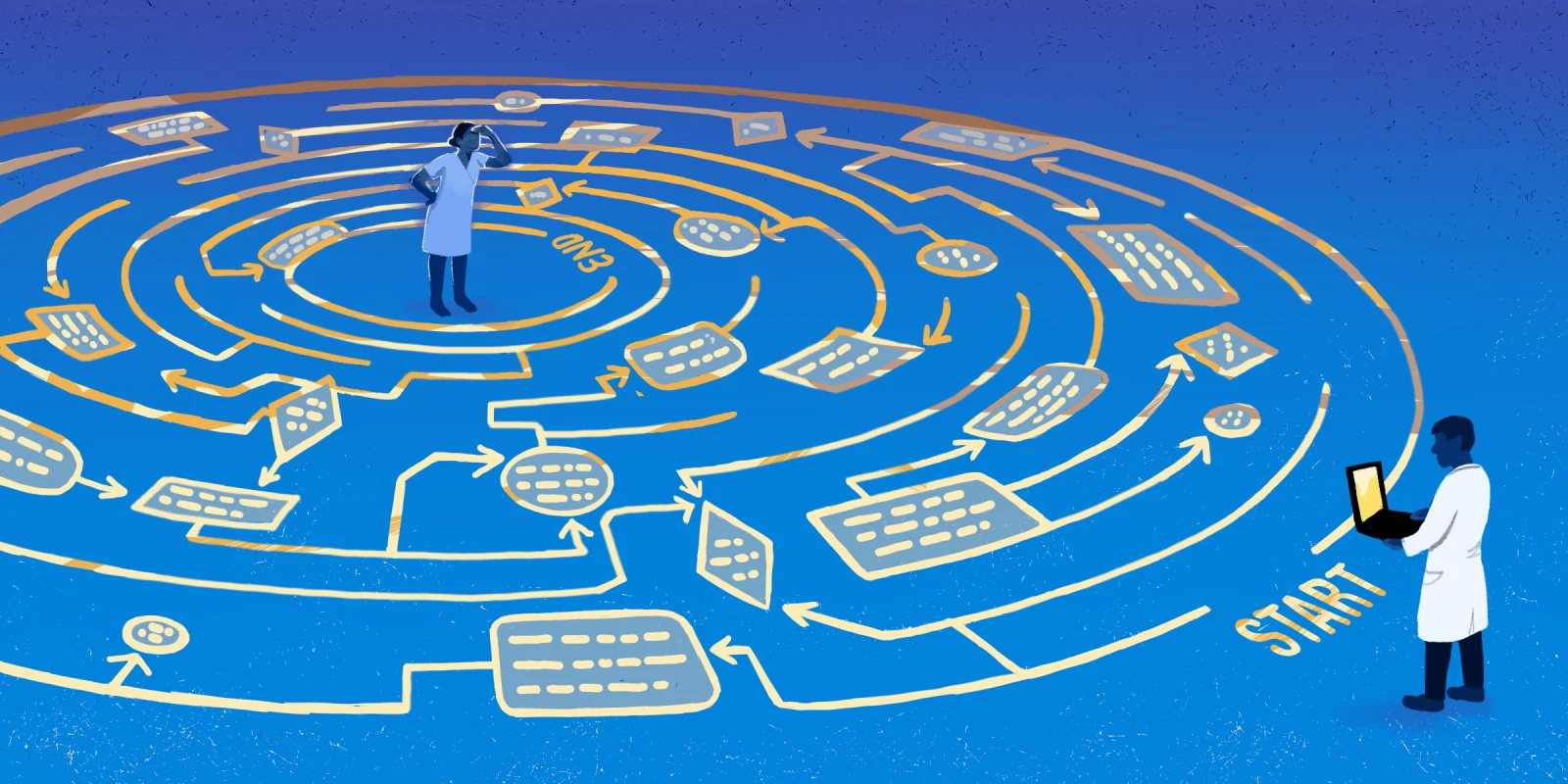

The promise of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in medicine has long been heralded as a revolutionary force — offering faster diagnoses, improved efficiency, and reduced human error. But while the headlines celebrate AI’s progress, few are willing to ask a more sobering question: What if this revolution is slowly edging physicians out of their own domain?

As a practicing gastroenterologist, I’ve watched this evolution firsthand. One of the first manifestations of AI in the field of gastroenterology was with polyp detection in screening colonoscopies. Computer-generated algorithms and image recognition learning modules integrated into endoscopy equipment can now identify colon polyps in real time, making it “easier” for the endoscopist to spot and remove them.

This sounds like a great advancement in the field, and in many ways it has been. The better the tools we have to detect polyps, the more effective we are at cancer prevention, right?

Well, a funny thing happened. The integration of AI into colonoscopy practice has given rise to other physicians — i.e., not gastroenterologists — performing screening colonoscopies as part of their practices. This includes surgeons, family medicine physicians, and even mid-level physicians.

To put things in perspective, basic colonoscopy proficiency has historically been a part of training for family medicine and general surgery residency programs, but most of these physicians do not actually end up incorporating this as a mainstay of their practices. Some do, especially in rural or underserved areas, but most refer these patients to gastroenterology.

Well, AI is changing that, and I’m not quite sure how I feel about it.

On one hand, there is a nationwide shortage of gastroenterologists, which is only going to worsen in the coming years, putting the general population at risk of not having enough access to an essential service such as the screening colonoscopy.

On the other hand, there now exist tools that can empower those who previously could not provide this service to offer it to patients in need, especially where GI specialists may not be available.

The data is certainly there to support the use of AI in colon polyp detection, with some studies showing that a novice endoscopist with AI assistance can identify colon polyps better than an ‘expert’ endoscopist.

But when I discuss these issues among my GI colleagues, while there is recognition of the issue at hand and the benefits of technology advancements, there is also a very distinctly visceral reaction that inevitably arises — to the effect of, “Wait a second. Isn’t the screening colonoscopy our job? If this ‘bread and butter’ procedure is slowly but surely eroded from beneath us, what will we be left with?”

I must say that I sympathize with my GI colleagues who are averse to “scope creep,” as it is colloquially known in GI circles. This resonates with me especially personally, since I was both inspired and trained by my own father — a practicing gastroenterologist of 40 years — in the art of colonoscopy.

As I have delved more into this idea of AI “helping” physicians do their jobs better, I also want to learn more about the other side of it — namely, the emotional and psychological toll it is taking on physicians who may no longer feel secure in their jobs, or perhaps question whether all the sleepless nights of med school, residency, and beyond were even worth it if nowadays an NP with an app wants to do the same job.

And the more physicians I talk to about this, I’m not quite sure how anyone feels about it, regardless of specialty, since AI seems to be infiltrating pretty much every medical discipline.

To be fair, the idea of “turf wars” is not a new thing in medicine. There have long been so-called “battles” between overlapping specialties to perform similar services — cardiology and interventional radiology, orthopedic spine surgery and neurosurgery, gastroenterology and colorectal surgery, the list goes on.

But somehow, this feels different. It feels like an entire paradigm of medicine as we know it is shifting. Not to sound overly dramatic or apocalyptic, but what happens when administrators, payers, or even regulatory bodies begin to prefer these technologies over trained professionals? When reimbursement favors machines over MDs? When hospital systems, under financial pressure, quietly reduce reliance on specialists in favor of “cost-effective” automation?

This isn’t speculation — it’s already happening.

In radiology, for example, hospitals used to almost universally staff an in-house radiologist 24 hours a day, seven days per week. This eventually gave way to the “more efficient and cost-effective” remotely based radiologist. With what we are now seeing in the medical technology space, is it really that far-fetched that hospitals may resort to AI-driven image recognition technologies as a defacto radiology service?

Is what was intended to be “supportive” actually becoming exclusionary?

What’s more troubling is that these decisions are often made without us. Physicians are not always consulted on the implementation of policies that directly impact their workflow, their compensation, or their role in patient care. Instead, we often spend precious hours adapting to systems and workflows regardless of how we may feel. Meanwhile, as the AI narrative continues to position AI as a potential solution to much of what is wrong in health care — burnout, inefficiency, cost overruns — perhaps less acknowledged is that over-reliance on it may be creating a new set of problems.

We cannot ignore the ethical implications of AI adoption either. Trust is an essential part of medicine. Patients place their lives in our hands, not in the hands of an algorithm. What happens when machines make errors? Who is liable? Who explains the decision to the patient? And more importantly, what happens to the physician-patient relationship when a screen is the new interface of care?

So what can we do?

First, we need to demand a seat at the table where these decisions are being made. If AI is going to reshape our field, physicians must shape AI. That means engaging in hospital committees, contributing to product development, and speaking out in professional forums like this one. Yes, this takes time and energy, almost always noncompensated.

Second, we must advocate for thoughtful implementation — not blind adoption. Not every innovation improves care. Efficiency should not be pursued at the expense of nuance, clinical judgment, or human empathy. We must be rigorous in evaluating the true impact of these technologies, not just on outcomes, but on the culture of medicine itself.

Third, we need to educate the next generation of physicians not just to use AI, but to critically assess it. Medical education must evolve to include digital literacy, ethical frameworks, and system-level thinking so that physicians remain the stewards — not the bystanders — of technological change.

There’s no doubt that AI will continue to advance. It will outperform humans in certain areas, and it will transform how we practice. But we must never lose sight of what makes medicine more than a science — it’s a human endeavor. The art of listening, the intuition built through years of experience, the ability to counsel a patient through fear and uncertainty — these are not things that can be programmed.

We are not obsolete. We are not replaceable. But we are at risk — if we remain passive observers of this shift.

Physicians must reassert our value, not just in outcomes, but in presence. In relationships. And most of all, in the irreplaceable role we play at the bedside.

If we don’t speak up now, we may one day find ourselves asking why we were the last to know we had been replaced.

How should physicians respond to AI’s growing role in clinical care? Share in the comments.

Dr. Neal Kaushal is a gastroenterologist in Oklahoma City, OK. He serves as executive director of general GI and endoscopy at OU Health (hospital of the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center). He also has a specialty in business operations and is passionate about the intersection of business and medicine to support patient access to care. He enjoys playing ball and going on walks with his three Dobermans, Rani, Riya, and Rishi. Dr. Kaushal is a 2024–2025 Doximity Op-Med Fellow.

Illustration by Diana Connolly