I hesitate at the gates. Closing my eyes, I steel my nerves and mentally prepare for the sight of death. I set foot into the temple, adorn myself with the appropriate PPE, and walk to my assigned cadaver. I glance up at my partner and sense a mutual feeling of apprehension. As our instructor makes introductions, I find myself staring at the ID card sticking out from the plastic bag covering the cadaver; instead of a name, a birthdate, or a picture, all things I normally associate with people, I only see a sequence of numbers. Numbers that tell me nothing about the life of the person I will soon be dissecting.

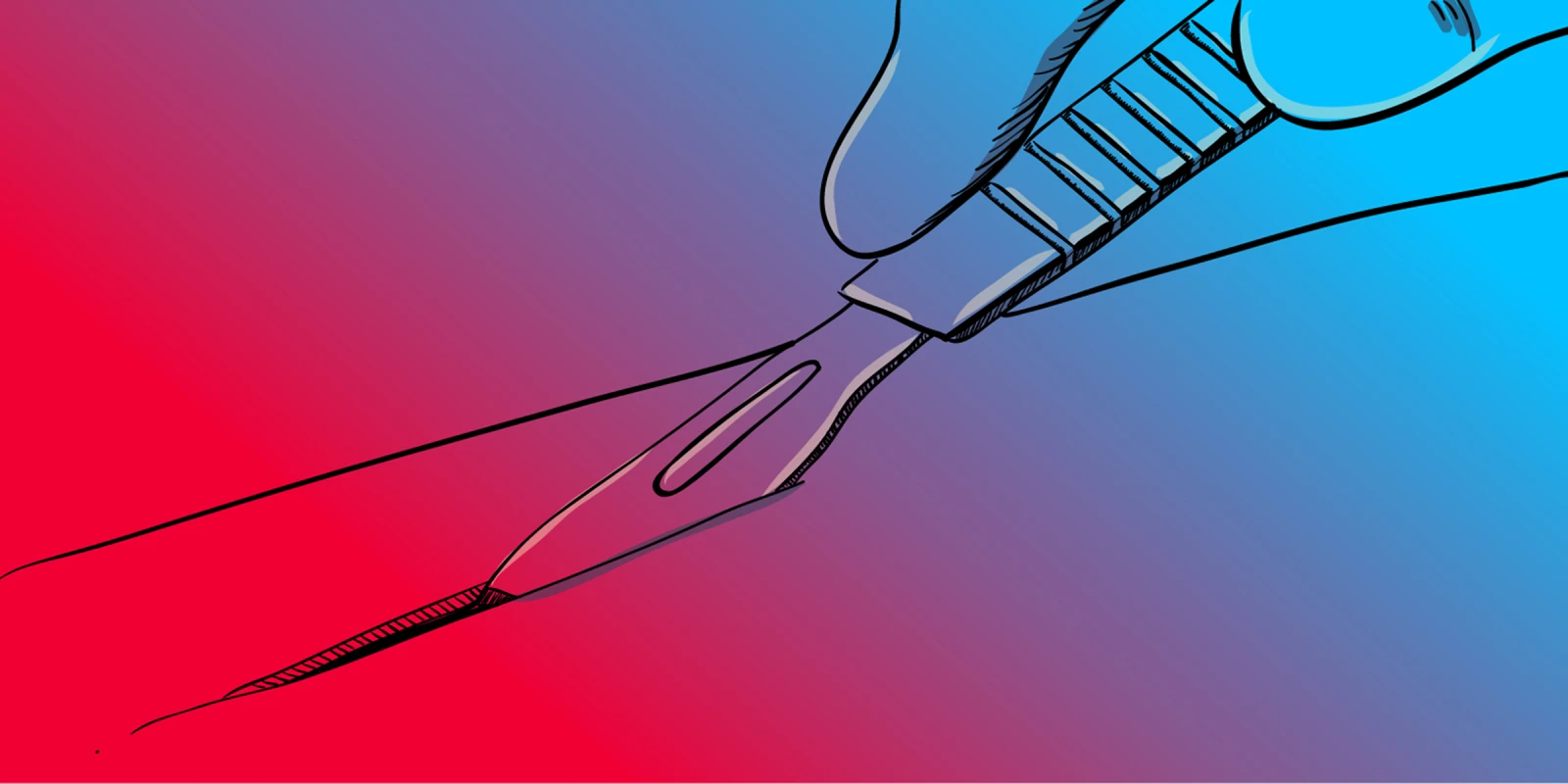

The bag zips open. This isn’t at all what I was expecting. Instead of normal skin tones, there are muted shades of yellow and grey. From lying on a steel table for so long, pressure points have manifested where the tissue has hardened, akin to plastic. This body is flatter than I imagined; there is less of the fullness associated with life. A simple rag covers the face of this person, this cadaver. I find myself relieved that I have yet to faint or vomit. Strangely enough, I feel at ease. We grasp onto stiff arms and manage to flip over this body. Taking my scalpel in hand, I double-check the diagrams illustrating the first incision on the back. I ask my partner if they would like to go first. They politely decline.

Here we go, the point of no return.

I ease my blade into the skin, dividing layers of fat and fascia. I continue down along the spine, trying not to overthink, until I reach the small of the back. I had expected to feel some profound emotion, but no such epiphany occurs. We work to remove the skin, to find the musculature that is hidden away. Each new cut teases what lies underneath: trapezius, rhomboids, latissimus dorsi. The labor is meticulous but rewarding. And it goes fast. I look up from the body that has become my project and am surprised to see that our time slot is finished. Storing my coat, lacing up my everyday shoes, I exit the temple. Yet as I walk home, I already feel a desire to return, to finish the task.

The following weeks demand more pilgrimages to this sacred space of anatomical learning. After opening the back, we lay bare the lower extremities, then the upper extremities. Unease has now been replaced by determination. I have to know every structure, nook, and cranny that can be found. As the labor continues, my mastery grows. I begin to take my newfound awareness into the other aspects of my life. Brushing my teeth, I examine my reflection and trace the branches of veins and arteries. At the gym, I see the contours of quadriceps and triceps brachii between sets. I scratch an itch on my hand and note the nerve that innervates that same portion of skin. Anatomy has become a lens through which I perceive the world anew.

Soon enough, we progress to the abdominal cavity. Never have I felt such an overpowering sense of awe. What had only previously been seen in illustrations and online diagrams was now laid out before me, in all its formaldehyde-tinged glory. As I cut away fat and probe the GI tract with cold metal instruments, I can’t help but feel sacrilegious. I remember learning how, during mummification, ancient Egyptians would store these same organs in canopic jars and place them under the protection of their deities. We will eventually dissect the brain and then the heart; in many cultures, both are seen as the essence of one’s soul. Just what will I think when those experiences arrive, how will it change me?

We strip the cadaver of tissue in order to create a specimen with which we can understand the body. I grapple with this seemingly dreadful exchange; in order to further my own understanding of what makes a human, we must cut away the things of which they are composed. Morbidity was absent in what was an objectively morbid act. We were, after all, working with corpses. With every pass of the scissors, with every stroke of the scalpel, I remind myself that this person agreed to be donated. Gratitude seems too small a word for the gift that they provided me.

How did you feel when you first worked with a cadaver? Let us know in the comments below.

Andrew Schmidt is a first year medical student at the University of Virginia, who graduated from the University of Louisville in 2020. In his free time, he enjoys rock-climbing, reading, playing video games, and hanging with friends.

Illustration by Yi-Min Chun