Only 55% of women physicians eligible for parental leave have taken the full amount, and half of those who did say it negatively impacted their career, according to a recent Doximity poll.

The poll of 1,558 women physicians underscores longstanding concerns over parental leave policies that have been described as inadequate industry-wide. There is currently no federal law mandating paid parental leave, despite recommendations from the American Academy of Pediatrics and other medical societies detailing its health benefits.

“In the early 2000s, it was not unusual for there to be no paid maternity leave at all and a pregnancy to be viewed as an inconvenience or disruption to the practice,” said Annette Lee, MD, a reproductive endocrinologist who had five children. “It was very hard to leave my kids to report by 6 a.m., but in those days you did what you had to do.”

Overall, a lower percentage of physicians (55%) took full parental leave than NPs and PAs (68%), suggesting that factors beyond workplace policy may be influencing the trend as well. Among a wide range of possible reasons include stigma among physicians for taking time off, a growing physician shortage, and concern over falling behind in a hypercompetitive field.

Among physicians, surgeons were less likely to take full parental leave than physicians in other specialties. Only 46% of surgeons reported taking full parental leave, compared with 59% of primary care physicians and 58% of nonsurgical specialists. Surgeons undergo longer residencies and tend to work more hours on average, both of which may have contributed to this trend.

Age also plays a major role, with younger physicians more likely to take full parental leave, according to the poll. The percentage of eligible women who took full parental leave was highest for those in their 30s (68%), followed by those in their 40s (59%). A considerably lower percentage of women in their 50s (41%), 60s (44%), and 70s (32%) have taken full leave. This trend may reflect an expansion of parental leave policies over time, or growing societal acceptance of its importance in recent years.

However, younger women report that taking more parental leave has increasingly hurt their careers. Roughly double the percentage of women in their 30s (36%) and 40s (32%) say that taking full leave negatively impacted their career, compared with women in their 50s (18%), 60s (15%), and 70s (18%).

In particular, surgeons report a steep penalty for taking leave. Among women who have taken full parental leave, a greater percentage of surgeons (59%) report that it negatively impacted their career than PCPs (46%) and nonsurgical specialists (50%).

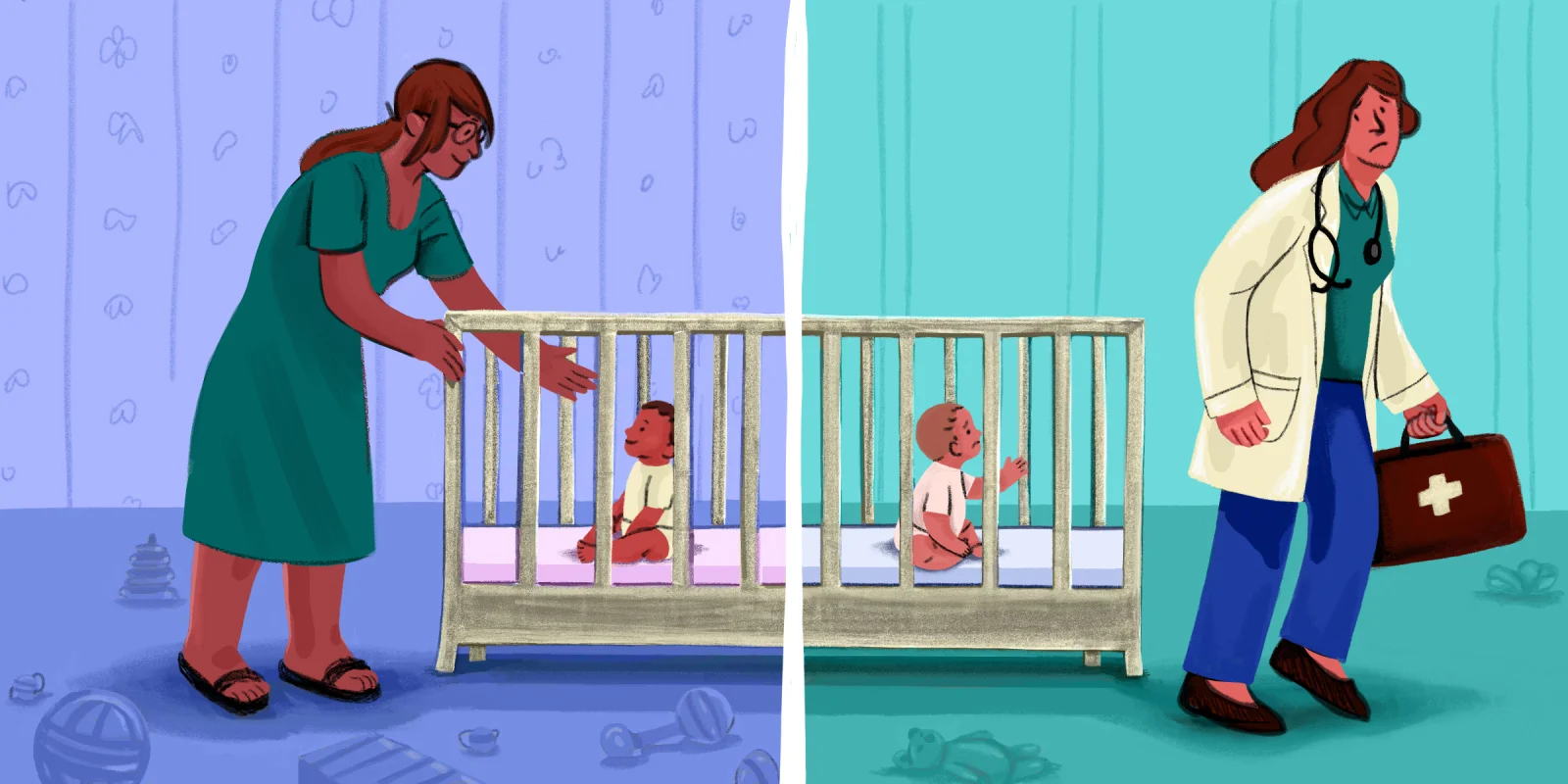

Research has shown that paid parental leave is associated with lower infant mortality and, potentially, longer-term health benefits for the child and mother. Though physicians typically recommend evidence-based practices for their patients, the poll results indicate that many of them may feel they are unable to follow the same advice when it comes to taking parental leave themselves.

In Dr. Lee's case, her family made the choice for her husband to become a stay-at-home spouse. “If I could do it over again, I wish I had had the opportunity to spend more time with my children when they were young,” she said, advising younger women in medicine to take all the time they need, paid or not. “Children will only be babies once. You have all your life to work.”

Amy Eichholz, MD, an ob/gyn, shared her experience when it came time to consider parental leave: “I was expected not to take full maternity leave to keep the call schedule ‘fair.’ This was delivered by one of my partners in a bullying, ‘no discussion’ way. I haven’t noticed views toward parental leave change, in my experience.”

In a large qualitative study of physician mothers, researchers identified the various forms that maternity bias — conscious or not — can take in medicine. Many physician mothers reported experiences of being held to higher standards than peers; being excluded from decision-making and advancement opportunities on the assumption that they’re too busy at home; a lack of support during pregnancy and post-delivery; and inflexibility with scheduling for child-care emergencies.

These physician experiences, among others, can affect women’s pregnancy and child-rearing decisions. In addition, they may contribute to lower job satisfaction, hamper career growth, and increase burnout.

Still, recent initiatives may help pave the way for improved parental leave policies. Both the ACGME and the American Board of Medical Specialties have recently published parental leave policies that are intended to support physician parents. A handful of specialty boards are also exploring competency-based medical education, allowing flexibility for leave during training by assessing competency rather than weeks of training completed. While they may not solve all of the challenges, these and similar efforts may help to change the culture surrounding physician parental leave.

Illustration by Diana Connolly