A quick scroll on social media is quite revealing of one thing: People don’t feel great, and they want relief from that.

Symptoms of relentless fatigue, weight gain, bloating, poor sleep, and depressed mood seem to plague much of American society. As we know, these symptoms could represent anything ranging from an aggressive cancer diagnosis to hypothyroidism to depression to nothing. Being faced with an unsolvable problem can be frustrating for clinicians but is understandably more frustrating for the patients who are living with the issue. Many patients chronicle their health journeys online, seeking advice and answers from others who suffer similarly. While this in itself can be therapeutic for patients, online discussions can generate speculation from the public about how health care professionals address and treat the trendy topic of balancing hormones.

Of course, we know hormone imbalance is real. We regularly treat adrenal insufficiency, Cushing’s disease, hypo- and hyperthyroidism, diabetes, PCOS, menopause, and the list goes on. Though not always curable, these diseases have clear criteria for diagnoses and consistent plans for treatment. Patients who are adequately treated will experience symptomatic relief to some extent. But how do we approach the patients with high- or low-normal hormone panels, or those with general symptoms that exist with normal workups, or those with no evidence to suggest hormone imbalance at all? While the easy answer is to not mess with a well-functioning system, how we handle patient concerns may create further problems for our patients, who may become targeted by social media influencers with misleading diagnoses and a “treatment” to sell them.

There are many common myths around hormone balancing, as summarized by an educational content creator Dr. Danielle Jones, an ob/gyn also known as Mama Dr. Jones. Familiarizing ourselves with these concepts can help us approach these discussions with understanding. One of these myths is called cycle syncing, which is a poorly-evidenced, highly-nuanced lifestyle that changes with each stage of the menstrual cycle and is thought to reduce PMS. Following regular implementation of its treatments of a strict diet and calculated exercise, patients will use their improvement as evidence of previous hormone imbalance, whether or not clinical evidence can confirm it. Practitioners regularly recommend diet and exercise to patients, as these interventions are well-known to improve health and sense of well-being. However, while there is no harm in our patients adopting that new lifestyle, we can encounter strife if this comes up in our discussions of diagnostic clarity.

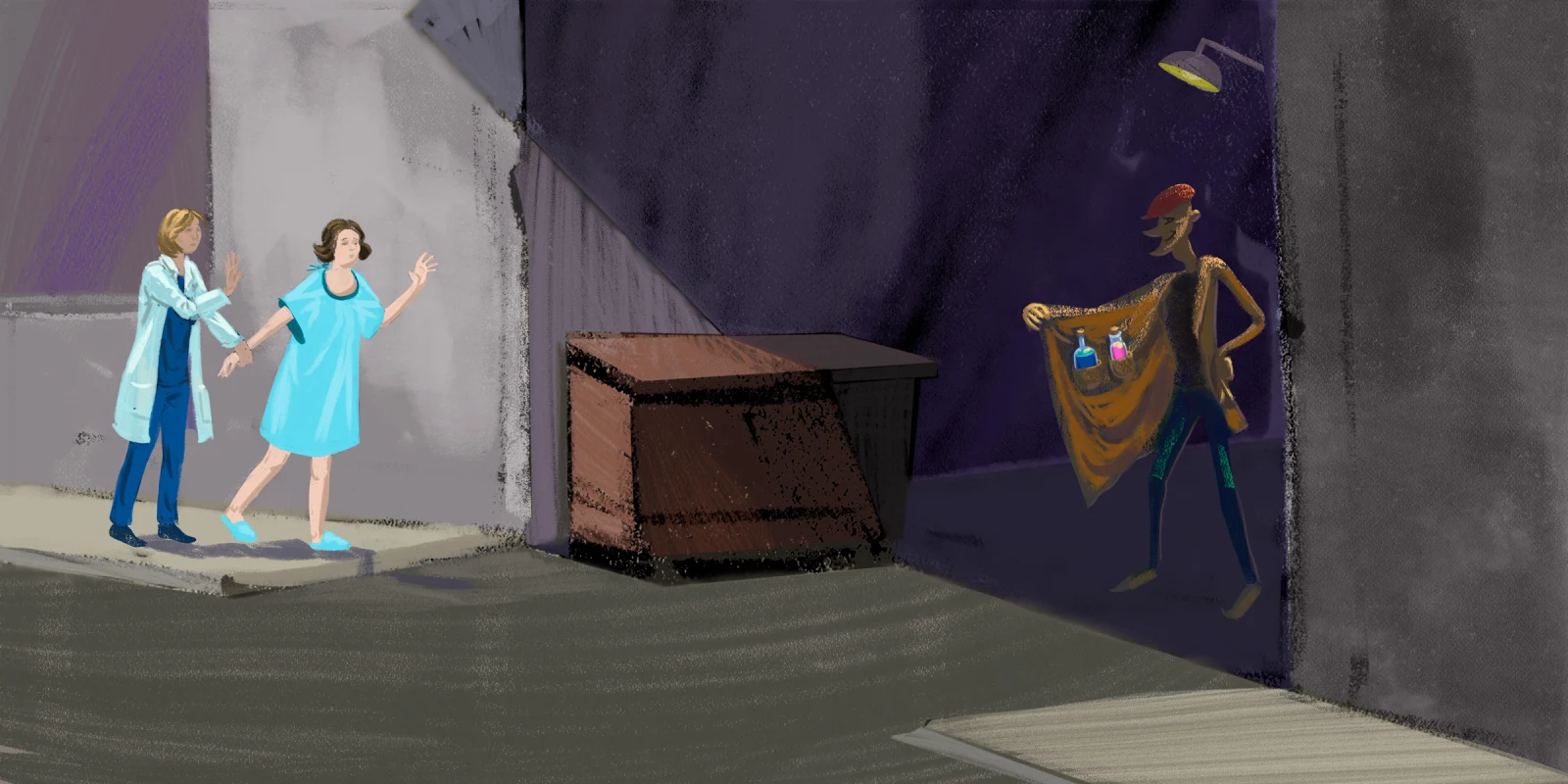

Another myth is hormone imbalance itself, which is often claimed by influencers to have those similar symptoms of fatigue, weight gain, bloating, and depression, and occur in the context of normal lab panels. This theory does not account for the natural fluctuation of hormones that occurs throughout the day and as one ages, and thus the diagnosis is made from non-evidence-based interpretation of point-in-time lab panels. This allows influencers to change the narrative on medicine: “Doctors don’t even know how to properly interpret those labs,” “Demand that your doctor document their refusal to do additional testing,” or “Doctors only spend one day in medical school learning about this. Message me instead.” These comments generate heated complaints and vent sessions in the comment sections on videos. As a physician on social media, it’s hard to ignore. The remedy offered by online health gurus for the hormone imbalance is often a paid “master” class on diet and exercise or an expensive (and possibly harmful) glorified multivitamin sold by the influencer. As practitioners, this situation can truly tie our hands. We cannot respond to online commentary, nor can we seem to shield our patients from the potential harm of these influencers.

Dr. Jones’s discussion sets the foundation of why this health trend is harmful. Health influencers, who often have no medical background, can emotionally and financially exploit vulnerable populations and possibly distract people from seeking professional medical care when needed.

An article by TIME Magazine further highlights the social implications of the hormone imbalance phenomenon. The article published in 2023 emphasizes that, despite the lack of evidence for hormone imbalance, the trend persists because it is based on how people feel. Additionally, by primarily addressing symptoms like fatigue, weight gain, or bloating, “thinness” and “usefulness” become equated to health. This enables influencers to disproportionately target women, who are generally expected to embody these values in American society. Prescribing diet, exercise, and supplements risks putting additional burden on those suffering (often postpartum or postmenopausal women) to “fix” themselves, rather than encouraging them to seek support in whatever form they truly need.

When it comes to hormone healing, unsubstantiated claims and lies regarding the medical profession further drive the divide between health care practitioners and patients. While this invalidation can be demoralizing for us, ultimately it’s the patient who suffers if we fail to provide clarity. After all, it’s the patients who feel unwell, and for many reasons they also feel as though they can’t trust us to fix that. What can we do?

First, let’s help them feel more comfortable with approaching us. For a multitude of reasons both within and beyond our control, our current practice of medicine has left no room for trust and relationship-building, the essential pieces of good patient care. We know that history-taking provides most of the information needed for diagnosis. How can we practice good listening? Sit down, make eye contact, nod, affirm, and don’t listen with the intent to respond. Instead, empathize with the validity of their concerns and the possible impact on their lives.

Next, we can empower them and make them feel in control of what’s going on. Our patients have Google and ChatGPT, and knowledge is power. Let’s figure out what they need to know to feel better. Are they worried about a certain pathology? Do they need someone to affirm they could use more support at home? What knowledge or assurance can we provide them to avoid unnecessary testing, medications, or the desire to seek care from non-medical professionals whose ideologies might harm them more?

Finally, we can create a home base. Some people will seek outside resources regardless of our recommendations. Think about how we can create a safe space for exploration. Rather than defending ourselves, can we collaborate with the patient to protect their best interests?

In the context of our health care system, this advice may be idealistic, as limited time, resources, and energy can minimize our ability to have meaningful conversations with our patients. However, we must be mindful that even if we can control little else within our day, how we make patients feel can make all the difference for them.

What health care scams have you heard about? Share in the comments.

Dr. Teresa Samson is a second-year internal medicine resident in San Antonio, TX. In her spare time, you'll find her sitting in the sunny corners of the hospital, FaceTiming with her family, and enjoying any excuse to be outdoors. You can follow her journey on Instagram at @residentdoctor_t. Dr. Samson is a 2023–2024 Doximity Op-Med Fellow.

Illustration by Jennifer Bogartz