It’s Thursday morning and the pathologist calls me with the biopsy results on my patient: cancer. Then comes my conundrum — when should I call her?

Three years ago, I would have called her without any hesitation and crossed that off my to-do list. I wouldn’t have wanted her to wait on pins and needles for the results. I would have wanted her to have a plan and start treatment right away. That’s what I would have wanted, but that was three years ago, and things have since changed.

Three years ago, on a Thursday morning, I had my first mammogram. It was routine, something to cross off my list. The results came back two hours later as suspicious. Five hours later, I was in breast radiology undergoing an ultrasound-guided biopsy. My friend, who happened to be the head of breast radiology, performed the procedure while another friend, the chief of breast surgery, examined me. They both reassured me that I would be okay.

For the rest of that day, I was in a haze. I couldn’t process what was going on. I tried to push it out of my head, but I couldn’t. Going unexpectedly from a routine exam to the possibility of cancer was too much for me to digest. I kept trying to convince myself that everything was going to be okay, that this was normal for a first-time mammogram on someone with fibrocystic breast changes.

The next day, I went to work and assisted my partner on a case. I kept looking at the clock, wondering when the results would come back. I was preoccupied with facing my mortality.

My friends — the surgeon and the radiologist — called me at 10 a.m. on a Friday, which was 26 hours after my mammogram, and told me that I had breast cancer. I felt everything in my life fall apart like a house of cards. And to be honest, I don’t remember the rest of the conversation. I cried uncontrollably and left the OR. I found myself in the locker room surrounded by friends, but I felt so alone, so afraid, so helpless. I could not get a hold of my family, and I just needed someone to take care of me as my soul crawled into the fetal position.

Driving home alone was one of the dumbest decisions I have ever made. I could barely see the road through my tears. I was not paying attention to the drive as I focused on the fact that I could die.

I spent the rest of the weekend sobbing uncontrollably while getting an MRI and preparing for my oncology appointment the following Monday. I cursed myself, regretting that I got the mammogram in the first place; I felt it was an egregious decision.

There is something to be said about ignorance being bliss. If I knew that Thursday was the last day I officially didn’t know I had cancer, I would have done more to appreciate that day.

How has this changed me as a surgeon? Now, I prefer not to call my patients with their results. I don’t want them to be alone when they get their diagnoses and then drive home by themselves. I want them to be mentally and emotionally prepared to receive the news.

What did I do with my patient? I called her on Monday. I wanted her to have one more weekend where she was cancer-free, where she did not have to think about chemotherapy, fertility, and her own mortality. When I saw her on Wednesday, she was still shell-shocked. Her face reflected a myriad of emotions, including fear, anger, sorrow, regret, and pain. I recognized that look because that was the same look I had three years ago.

Sharon Ben-Or, M.D. is a thoracic surgeon from Baltimore. I enjoy hiking, cooking, and yoga.

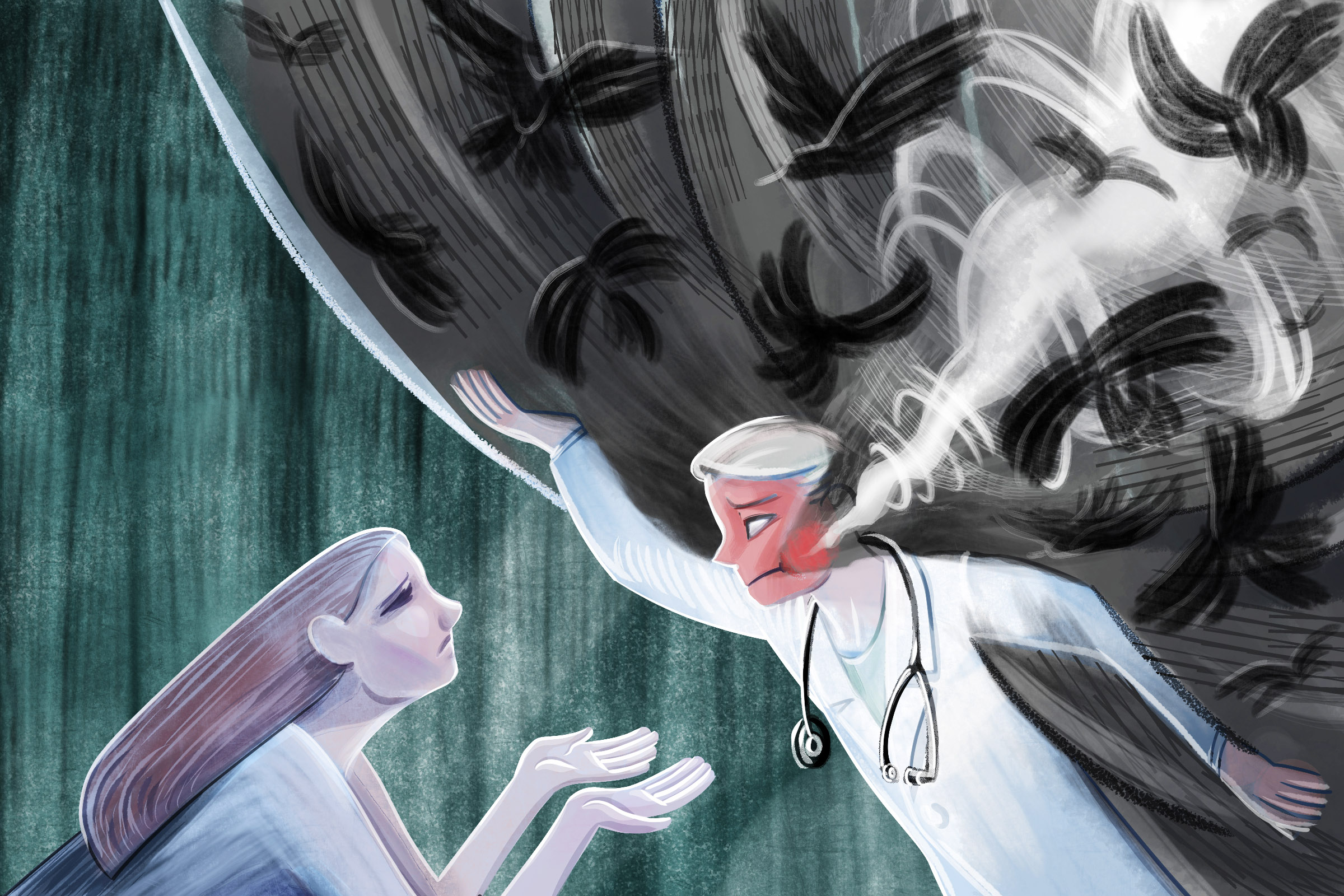

Illustration by April Brust