Last year, while on my trauma rotation, I wrote “We are Drowning,” a narrative reflection about physician burnout and the daily tragedies we witness. Within a few weeks, the piece had gained over 50,000 views and my email inbox was flooded with responses. Most of these responses were from residents and other physicians who said my feelings of profound sadness and moral injury resonated with them. The daily tragedies we see and our inability to take time to process these moments have been taking their toll. Physicians from all over the country, both retired and early-career physicians, felt a connection to my words. I felt a sense of community, connection, and understanding.

And yet I also received countless responses that seemed to miss the very points I wrote about — burnout, disconnection, and physician mental health — and turned systemic issues into my own personal failings. Other physicians told me I wasn’t cut out for a life in medicine. They diagnosed me with psychiatric issues without knowing me: PTSD, depression, anxiety. They told me that my path would lead to suicide — and soon. They encouraged me to step away from the medical field, portraying their guidance in a loving, caring manner. Staying in medicine, they said, would cause me to “lose my humanity.” I was told to quit residency or transfer, blaming my specific institution, when in reality, many causes of burnout are larger systemic issues. Others recommended I find a completely new field of medicine to lean into, suggesting pediatrics or ob/gyn. I’m sure it’s just a coincidence that both of these fields are predominantly female. Hopefully they were not insinuating that my vulnerable emotions would fit in easier in specialties with more women, surely not correlating my emotions with femininity and weakness. It couldn’t be because pediatrics or ob/gyn are less tragic than trauma and emergency medicine — that’s far from the truth. Even so, medicine isn’t a competition for the most tragic experiences.

It was pointed out that by speaking out about my proximity to daily tragedies, I wasn’t focusing on the good experiences, that I was missing out on furthering my medical education, as if discussing tragedy is incompatible with appreciating the beauty of our work or with learning. Many writers also recommended that I pray and urged me to find religion, saying I should prioritize prayer over therapy or psychiatric help, despite knowing nothing about my religious background. Others critiqued me for my admission of guilt — my anger at patients amid periods of intense burnout, my short temper, my impatience — saying I should be more empathetic and caring, yet not affording me that same empathy during my hardest times.

Why do these responses matter? Why do I care? They reflect the undercurrent of our medical system, a compendium of physician beliefs about mental health in medicine. Physicians from around the country contacted me, representing leaders from various hospitals, fields, and departments. I may as well have received these responses to my face: “You’re not cut out for this”; “Have you thought about quitting medicine?”; “Maybe an easier specialty?” To them, I was too weak, too emotional. Maybe I should be grateful that so many of these responses expressed concern about my mental health — but none of these commentators asked how I personally felt or how I was doing. They labeled me with their findings and warned me of the impending doom to come. These responses are exactly the reason why I wrote my initial piece: to call attention to the current woefully inadequate nature of mental health in medicine, to highlight the ease with which we dismiss pain or place blame when it doesn’t emerge from our patients. Now with another year of residency behind me and these responses in mind I want to return to this conversation: Has anything changed? What can we do?

When we as trainees express our sadness, our depression, why is the first assumption that we are not cut out for this career? Why would my expression of vulnerability be interpreted as an admission of weakness? Why am I the one expected to change — to be less emotional, switch specialties, or leave medicine entirely? Instead, why don’t we try to change our field to meet our compassion and humanity rather than change ourselves in order to fit the unforgiving mold?

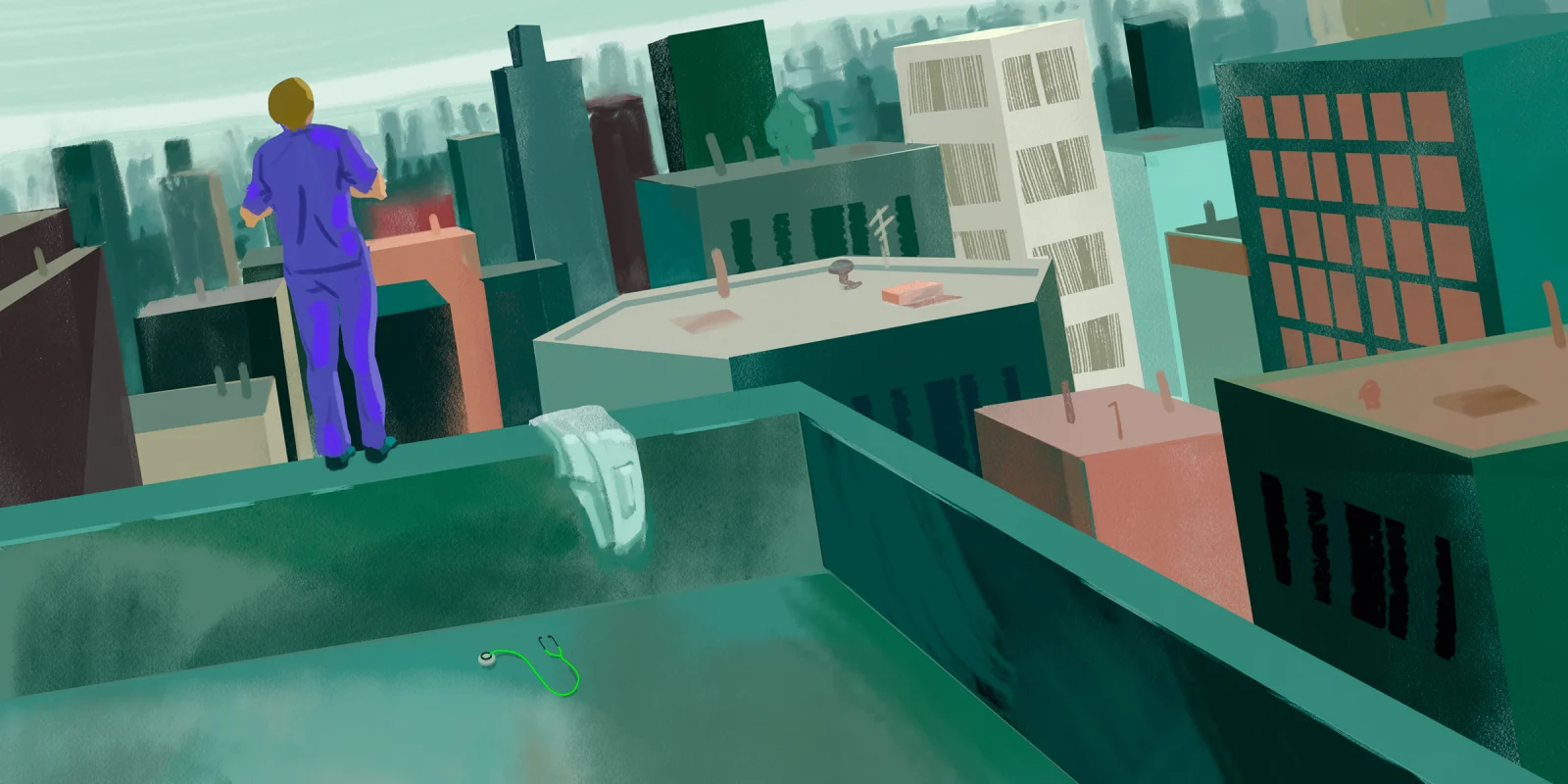

The cruel joke is that even when we do try to change — go to therapy, try medications, see a psychiatrist — it is often not enough. I log into Twitter as I’m walking into my pediatric ICU shift and see a post about another young resident who has killed herself. I read her loved one’s words of devastation and grief. I think about her all day, about her family, her co-residents. She is all of us and we are all her. About 300-400 physicians in the U.S. die every year by suicide. These numbers are higher among women physicians than women in other professions. And medical training has no sympathy for even our youngest trainees, medical students, who have rates of depression up to 30% higher than the general public. And how could this not be true? Our profession isolates us, crushes us with debt, requires us to work long hours with minimal time off, encourages lying when we record our hours worked so we don’t go over the 80-hours-a-week limit, and disincentivizes us from putting our needs and health first. We feel we are never enough — never enough of a doctor, partner, sibling, friend. But we are not weak, and we are not the origin of the problem. Medical training is killing us and has no intention of letting up. We need change, and we need it now.

We have already seen some recent strides: As of July 1, 2022, the ACGME implemented six weeks of parental leave to residents and fellows. The Dr. Lorna Breen Act, named after Dr. Lorna Breen who died by suicide in 2020 during the initial COVID-19 wave, was passed earlier this year and serves to increase funding for mental health structures to support physicians.

What is next? Improve sick call policies so residents can call out sick without the fear of burdening resident colleagues. Do other residents always need to be called in, or can the team and attending manage without them? Increase our wages to reflect inflation and cost of living. Improve access to mental health professionals, and make it possible for us to take a few hours off to attend medical appointments. Fairly distribute our days off so residents aren’t working 14 days straight. Eliminate 24-hour call. Unionize.

What changes do you believe would help improve the residency experience? Share your thoughts in the comment section.

Dr. Halloran is an emergency medicine physician currently completing residency in Chicago. She works and writes at the intersection of health policy, inequality, and education, and her research and writing has been featured by the American College of Emergency Physicians and by Slate. She can be found on Twitter at @Diana_Halloran. Dr. Halloran is a 2022-2023 Doximity Op-Med Fellow.

If you or someone close to you is experiencing thoughts of suicide, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 or text HELLO to the Crisis Text Line at 741741.

Illustration by Jennifer Bogartz