It’s no secret that maternal care in the U.S. leaves much to be desired. Among all high-resource nations, the U.S. is the only one with a constantly rising maternal mortality rate. Meanwhile, according to the WHO, maternal mortality rates declined between 2000 to 2020 in most countries, even less developed countries, while continuing to rise by almost 80% in the U.S.

While increasing rates of obesity and cardiovascular conditions in the U.S. may be contributing to these numbers, blaming premorbid maternal health does not paint the full picture. Women, from Olympic athletes to movie stars, have also suffered from pregnancy-related complications including preeclampsia, postpartum hemorrhage, respiratory distress, and even death. Some argue that the U.S. is one of the more dangerous places to give birth among high-income nations. Such statements should be nothing short of alarming, and thus, it should be no surprise that the rate of postpartum depression and anxiety is high.

Pregnancy is a seismic experience. Women undergo lifelong changes while pregnant, both visible and invisible. In fact, the impact of pregnancy on the body and the brain is comparable only to that of adolescence. Yet, even among countries rich and poor, the U.S. is still one of the only countries that does not seem to recognize the magnitude of pregnancy and the impact of parenthood. The U.S. has neither tradition nor policy for parenthood.

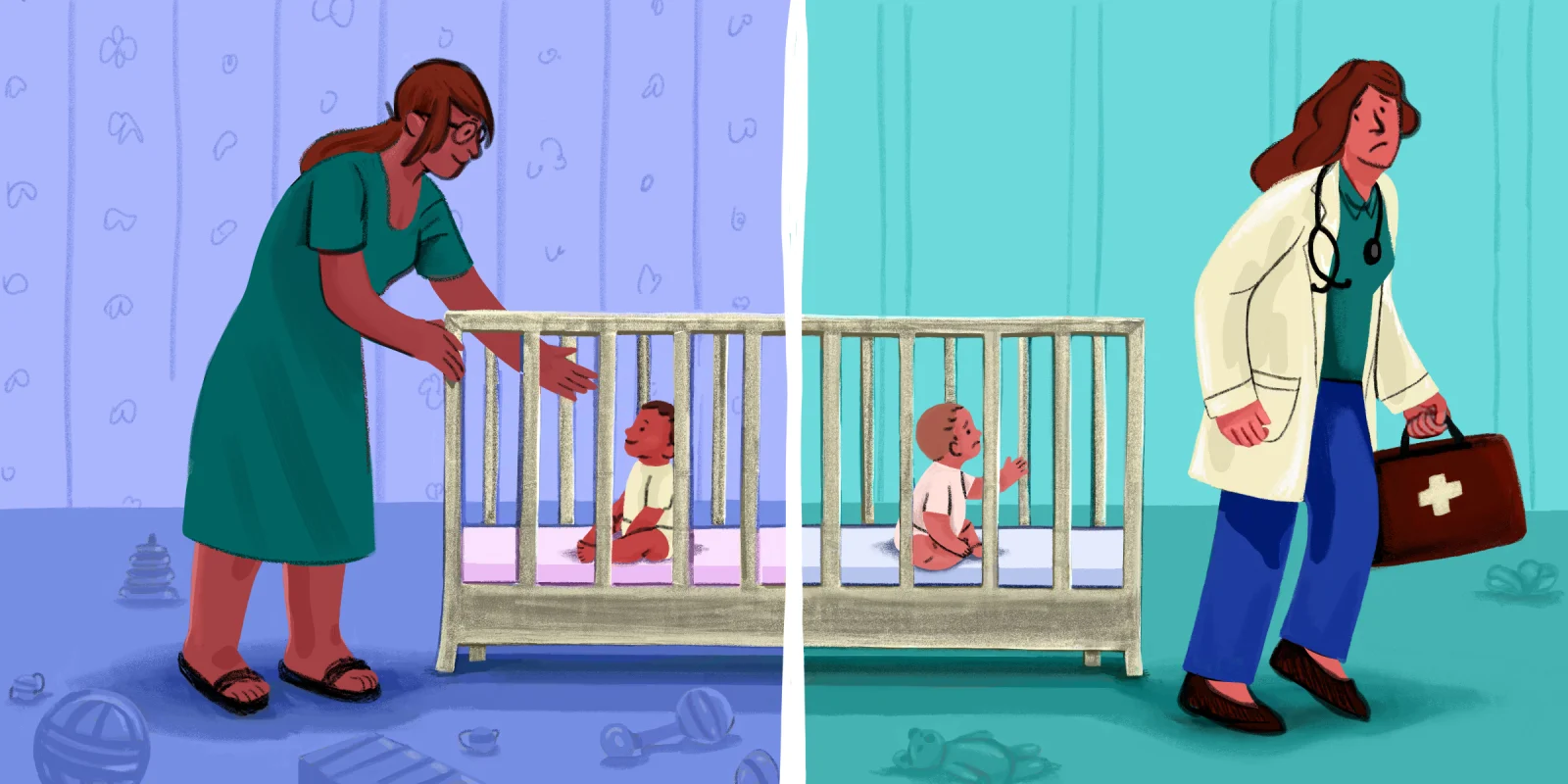

Instead, six weeks after delivery, new mothers in the U.S. are left to care for themselves — and their newborn. At this timemark, OBs typically release women into the care of their PCPs. Most PCPs, however, are overworked and burnt out, and the focus of primary care is on chronic issues and health maintenance as opposed to postpartum rehabilitation. A visit to the primary care office for a postpartum issue, at that point, seems irrelevant.

Thus, the burden of continued health maintenance falls onto the mother. Women are left to seek support from friends and family members, and those who have the means might hire additional services such as postpartum doulas and night nurses.

Meanwhile, America’s postpartum society puts an immense amount of pressure on women to “bounce back,” which sets unhealthy and unrealistic expectations. The pressure to return to a prepregnancy self can lead to resumption of high levels of activity that may put women at risk for delayed healing and increased injury. Despite ongoing internal healing, a mom’s postpartum experience is judged based on how she looks rather than how she feels.

If these societal expectations weren’t demanding enough, one in four women return to work two weeks after childbirth. This is despite the recommendation by medical societies for 12 weeks of paid parental leave, with six to nine months being ideal. While benefits of paid parental leave are numerous for society as a whole, there remains no federal policy for paid parental leave in the U.S. A lack of such policies forces many women to return to work, often for financial reasons but occasionally due to peer pressure.

Today, there are more women in the workforce than ever. Women are now, on average, more college-educated than men and now surpass men in medical school enrollment. Not supplying an adequate bridge back to the workforce causes some mothers to temporarily or permanently leave the labor force. This is a huge talent drain for American society. In medicine, where physician shortages are already a concern, a failure to support women who choose to become mothers will lead to a public health crisis.

In comparison, many countries around the world have parental policies to support the postpartum period. Sweden, for example, offers 480 days of parental benefit per child at 80% of their normal income. In Canada, parental benefits can be paid for up to 35 weeks at 55% of income. Meanwhile, the U.S. offers only 12 weeks of job protection and there is no guarantee that those weeks are paid.

Many countries are also rich in traditions that honor the postpartum journey. In Asian cultures, new mothers follow the tradition of confinement or “sitting the month.” This is a period during which new mothers stay at home and follow a restricted diet and lifestyle to allow the body to heal after birth. In Latin American cultures, la cuarentena is a similar practice that involves 40 days dedicated to rest and postpartum recovery. The common theme among these traditions is respect for the postpartum experience and the acknowledgment that women must be supported as they transition to motherhood. Meanwhile, the culture in the U.S. is focused on getting women back to the way they were rather than meeting them where they have gone.

Motherhood is a life-changing event that can leave families extremely vulnerable. There is much that we can learn about the sacredness of the postpartum experience from the policies and traditions around the world. As Americans, we need to shift away from unrealistic expectations and come together to support new mothers.

What are your thoughts on postpartum policies in the U.S.? Share in the comments.

Thea L. Swenson received a bachelor’s degree in engineering, product design from Stanford University and a medical degree from the University of Colorado. She is currently a resident in physical medicine and rehabilitation at Vanderbilt University and hopes to specialize in sports medicine. Thea was a 2022–2023 Doximity Op-Med Fellow.

Illustration by Diana Connolly