It was 4 a.m. and nearing the end of a long night shift. All the fetal heart rate monitors showed well-behaving babies and I desperately felt the beckoning of my call room bed. Suddenly, one of the heart rate tracings plummeted. Ninety-nine percent of the time this type of deceleration resolves quickly. Things don’t just instantly change from OK to life-threatening — except when they do. We did the typical things that usually work to fix the problem, turning the patient from side to side, stopping pitocin, etc., and they all failed. We needed to rapidly deliver the baby for her to survive. And we did just that. Mom and baby did well with the baby going to the NICU, but at 36 weeks this was not entirely unexpected.

Several hours later, I emerged from post call sleep. Post call is not the same as being off, so with one eye scrunched closed and a still foggy brain, I opened my email. The quality NP had written inquiring about our delivery. There had been equipment issues that had made the delivery even more harrowing than usual. An incident report had been filed and the quality NP wanted to know if the equipment problem contributed to the infant’s NICU admission (it had not).

Over time, this case became etched into my mind as emblematic of the negative feedback loop that often occurs in the practice of medicine. We had been tasked with performing a life-saving procedure and we had done it. Yet the quality NP’s email was the only feedback I ever received about this case. And I hate to admit it, but this nagged at me in a way I couldn’t easily shake off. The fact that it bothered me was also annoying. Why couldn’t I be like those heroes who respond to praise by simply saying it was nothing, they were just doing their jobs? It took time to realize a key truth: You get the chance to say you were just doing your job only after someone recognizes your actions.

Ironically, realities such as this exist in an era in which feedback is increasingly prized during medical training. Years ago, we were encouraged to preface teaching with phrases like, “Let’s do some teaching about x” so that it would be clear and appreciated that a teaching moment was forthcoming. Now we are advised to set the stage for feedback with similar introductions.

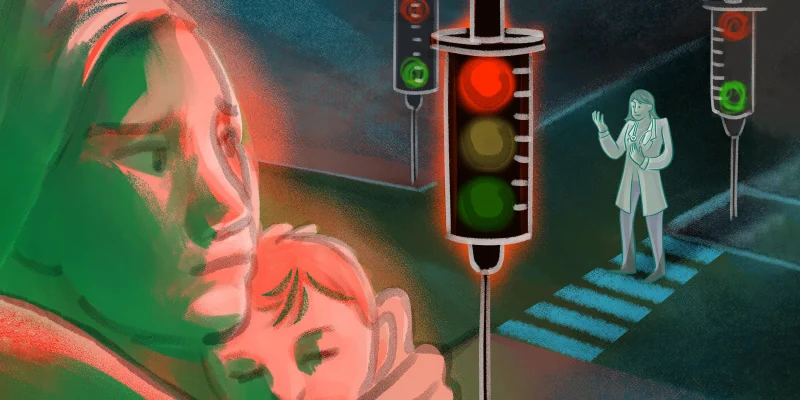

However, when the clock strikes midnight on medical training, most people will find themselves in a feedback carriage that looks a lot like a pumpkin. The truth is, the practice of medicine can often feel like the ultimate negative feedback loop: No or very little meaningful positive feedback, and the feedback that does make an impact often feels really negative — think negative patient reviews, lawsuits, tragic outcomes.

In obstetrics, this can be particularly acute. When the goal is the trifecta of a healthy mother, a healthy baby, and a meaningful, positive, and not too arduous birth experience, it can seem likely that we will often fail. It’s not that patients don’t express gratitude to us, because they do. But often it seems that the families who are the most thankful are those for whom we have done the least. They showed up, their birth went smoothly, their baby healthy and adorable. Their gratitude, while heartfelt, feels like it would be better directed to a divine power or the universe that blessed them with a good birth experience than to their medical team. The births in which we help the most tend to be the ones in which nothing goes according to plan and everything is hard. But when your vision of birth starts with candles, spa music, and essential oils and ends instead under bright OR lights, it can engender shock and disappointment that make it hard to feel, much less express, gratitude. And when something has ended up so differently from what you expected and hoped for, it can understandably feel like instead of someone to thank, there might be someone to blame.

We need to continue to teach and give feedback to learners. However, some warning might be in order that, if all goes well, you will have a long career in medicine. And for most of that time, you will probably receive no, or very few, awards, prizes, or positive evaluations.

Eventually, how to get by, and thrive, with less then becomes the question. I’ve always been a believer in soaking up the positive and trying to savor the moments when things go well. But humans are evolutionarily designed to feel the negative more intensely than the positive. And by focusing on the positive, are we still just chaining ourselves to a need for validation in order to keep going?

How can we be tasked with doing nearly impossible things and be OK with doing them just for their own sake? How can we move beyond our need for recognition and praise? To investigate these questions, I searched for inspiration through an internet search that went something like, “Buddhist quote for doing things without seeking recognition.” I am embarrassed to admit that I was actually disappointed when I couldn’t quickly find a wise adage that would instantly cure me of this shortcoming.

The truth is that growth requires building muscles and won’t just be found in a quick quote or internet search. And maybe it’s not even realistic to think we can evolve our way into a state where we don’t ever need the little pick me up of being told we’re doing a good job. Awareness is always the first step. Knowing that a positive feedback void can exist for all of us might help us better lift up not only ourselves, but others around us.

And when I think about it, how often do I reach out and commend my partners and team members when I see them do an awesome job in a really hard situation? Definitely not often enough. How differently would the quality NP’s email have landed if it had included an acknowledgment of how challenging our case was and what a great job the team did? We’re all human and we could all use some positive feedback from time to time. And this reminds me of the quote I did find in my internet enlightenment search, “When you light your lamp for someone else, it will also brighten your own path.” The path can definitely seem dark at times. And we all could use more light.

How has negative feedback affected you? Share in the comments.

Dr. Jennifer Boyle is an ob/gyn who lives in Boston, MA with her husband and her three teenage children. In her free time, she runs, reads, and bonds with her labradoodle, Teddie. Dr. Boyle was a 2022–2023 and 2023–2024 Doximity Op-Med Fellow.

Image by akindo / Getty