An Introduction to Inflammatory Breast Cancer

Breast cancer has a month dedicated to its awareness each year, and while there are common warning signs for most breast cancers — a patient complains about a lump or a different feeling in their breast — there are often not as obvious symptoms for inflammatory breast cancer (IBC).

I did not always treat IBC. I originally was a transplant physician, and when I switched to treating breast cancer, I looked for the underserved population within that. Treating IBC, an aggressive metastatic disease, seemed to be the best fit because it’s rare.

Though inflammatory breast cancer represents only about 2–4% of all breast cancers, it is the cause of more than 10% of breast cancer deaths in the U.S. Therefore, it is crucial to ensure that we, as physicians, are aware of the challenges in detecting, diagnosing and treating this disease in order to give our patients the best chance for good outcomes.

Detection & Diagnosis of IBC

It’s frustrating when IBC originally receives incorrect diagnoses, which in turn creates more time for the cancer to metastasize. When the patient first goes to their primary care provider, it is often misdiagnosed because it has different warning signs than other breast cancers.

If IBC does not present with typical warning signs that other breast cancers come with, how can we as physicians accurately detect and diagnose it?

It isn’t that IBC presents with no symptoms. Generally, IBC symptoms include the breast showing redness, peau d’orange appearance, and swelling, as well as being warm to the touch. In fact, it can appear very similar to mastitis, or infection of the breast.

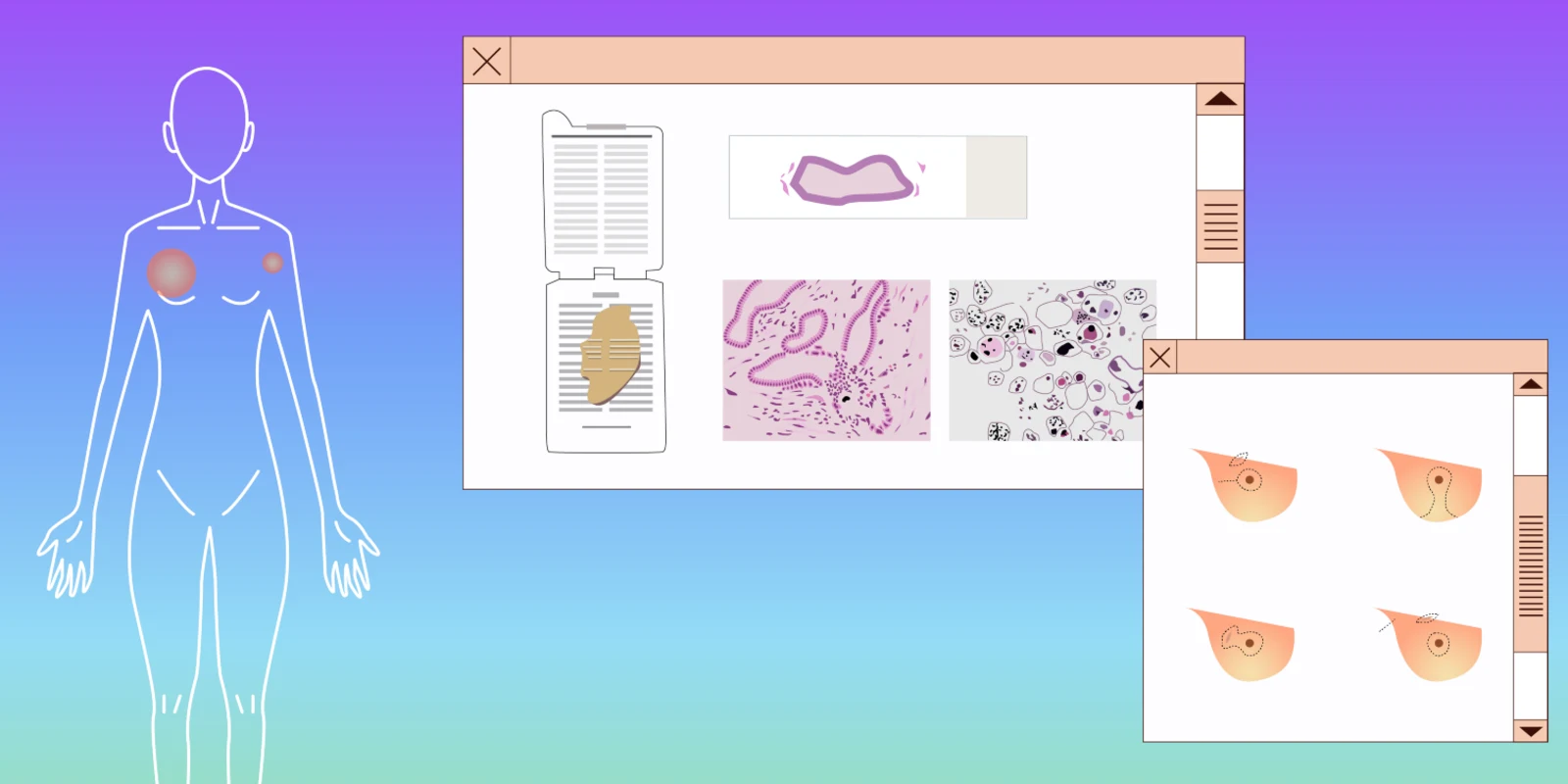

If a physician does suspect IBC, it may still be hard to get an accurate diagnosis. Because IBC does not always present with a mass, an ultrasound and/or mammogram shows only an engorged breast, skin thickening, and breast tissue changes. The question for the radiologist or surgeon then becomes, “Where should I biopsy?”

If there is not a mass, we recommend performing biopsies of both the abnormal looking skin and the breast tissue that appears to be most distorted. Compared to non-IBC, IBC tumors are scattered among the tissue section in many cases. That means a negative first biopsy does not necessarily rule out IBC. If the skin changes do not improve, a second biopsy is highly recommended.

Without a timely diagnosis, we may be allowing a fatal disease to progress. IBC has the worst prognosis compared to all other types of breast cancer, caused by a rapid progression of disease leading to widely metastatic cancer. In 1/3 of the cases by the time the patient is diagnosed with IBC, the cancer had metastasized.

Treating IBC

Because of IBC appearing as similar to mastitis, many physicians will simply prescribe antibiotics. However, most IBC cases do not respond to antibiotics, though some can have a partial response or stop spreading, which creates more confusion. Based on the partial response, clinicians may believe the patient has an antibiotic-resistant mastitis, which results in them being treated with a second round of antibiotics. By the time they have gone through antibiotic treatment, the inflammatory breast cancer has been given time to spread and metastasize, which is nearly fatal for the patient.

After you have successfully determined it is IBC the question is how to treat this disease. There are four points that you need to know.

- Standard-of-care treatment is preoperative chemotherapy followed by surgery and radiation therapy. We have had patients come to us who have had surgery first, which is unhelpful when the breast has been removed without any pictures to show us where the problem was in the first place.

- It is essential to rule out distant metastases. Even if you find a distant metastatic disease, it may be worth exploring the multidisciplinary approaches (surgery and radiation therapy in addition to chemotherapy) in certain clinical scenarios.

- It is critical to achieve maximum response to chemotherapy before surgery.

- Surgery is modified radical mastectomy.

Unfortunately, approximately 1/3 of cases in the U.S. do not receive standard-of-care treatment. For best outcomes, patients need to see a good team of oncologists who are familiar with treating this specific, aggressive form of breast cancer.

For example, I helped develop a clinically-oriented, translational research-focused IBC program at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center where we had a network of multidisciplinary clinicians and researchers to design and conduct IBC clinical trials, as well as secure and maintain bio-specimens and clinical data resources. We have the world’s largest clinic for treating IBC.

Primary care physicians and dermatologists, while experts in their field, often misdiagnose IBC as something else, wasting valuable time in starting treatment. Usually by the time the patient comes to us, a considerable amount of damage has been done.

Challenges in Diagnosing and Treating IBC

- IBC can appear as similar to mastitis, leading doctors to prescribe antibiotics. IBC may respond partially to these antibiotics but cannot be fully treated this way.

- A negative first biopsy does not necessarily rule out IBC because tumors can be spread about.

- Standard care is not sufficient to achieve the highest rate of control or cure of the disease. Even after receiving the best standard treatment, there is still a high risk for the disease to recur. There is pervasive research ongoing to understand the cancer stem cells and cancer microenvironment, which leads to innovative therapy.

- Requires network of doctors: timely detection and diagnosis from vigilance by primary care physicians (such as gynecologists, internists, emergency room doctors) and treatment by oncologists.