During my first year of medical school, I remember being shocked as I learned that certain ZIP codes of San Antonio were associated with a 20-year shorter life expectancy. At the time, my medical school had us making quarterly visits to the homes of underserved families. During these visits, we would chat with families about their lives with the goal of discerning their social determinants of health. Our family included a mother and father with several children. They lived in a small apartment located far outside of San Antonio. Their location in rural Texas, we would learn, was only the first of many intertwined barriers to health.

Shortly after we began visiting the family, we had increasing difficulty getting in touch with them for follow-up visits. One of the parents, who worked in industry, suffered an injury and had to take leave from work. They struggled to get approved for disability insurance. Simultaneously, the family’s single car needed repairs. Due to the parents’ unemployment status, they could not afford the repairs and therefore struggled to transport their kids to school and make supplemental income. Where they lived, public transportation was not available. Needless to say, these circumstances also limited their follow-up doctor appointments for their ongoing medical conditions. As medical students, our role was strictly to offer a listening ear rather than intervene with their struggles. We felt helpless each time we left, unable to provide what we thought they might need. Eventually, we lost touch with the family as they understandably prioritized their more pressing needs.

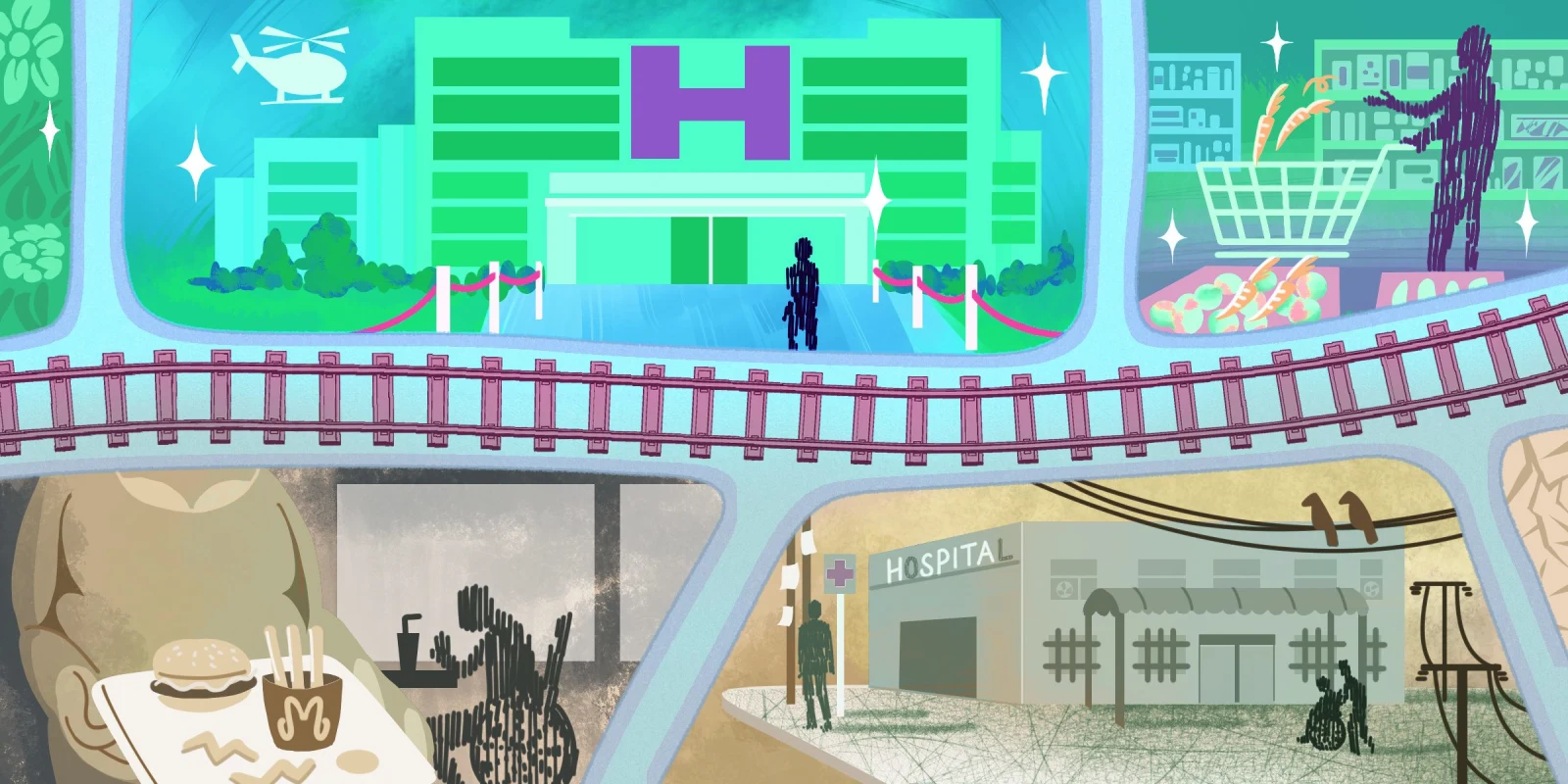

While health status, career setbacks, and transportation were obvious barriers for this family, we learned that their location in rural Texas was an important overarching factor in their wellbeing. Population studies over the past 10 years suggest that ZIP codes may be more predictive than genetic code when considering population health outcomes. Data collected in a pre-pandemic San Antonio population study further elucidates this association of location with other social determinants of health by mapping various demographics by ZIP code.

This data shows that, although the family struggled in unique ways, their struggles were largely representative of those of their local community. Prior to the pandemic, up to 10% of residents in their ZIP code struggled alongside them with unemployment, this rate being greater than the county rate of 7.5%. Alongside this, their neighboring households shared a median income of $38,000 – $56,000, which fell below the county median of $58,000. Up to 15% of their neighbors lived below the poverty line. Countywide, about 36% of residents have an associates degree or higher, which accounts for less than 17% of their community. The known correlation of education levels with health outcomes was demonstrated by higher rates of COVID-19 infections in patients with lower levels of education. Altogether, their ZIP code demonstrated a pre-pandemic life expectancy 10 years shorter than average life expectancy in other areas of San Antonio, and at least one year shorter than the countywide three-year average of 78.9 years. While these data cannot suggest a causative effect for shorter lifespan, the trends highlighted the association and possible role of location with financial, educational, and health outcomes. One can reasonably expect the upcoming data will reflect that COVID-19 exacerbated these disparities.

What was so shocking at the beginning of medical school now seems intuitive as I have gained exposure and experience addressing health in the context of health disparities. I always imagined going the extra mile for my patients but now realize that the barriers to health are much greater than what can be addressed at one visit, during one hospitalization, or even during one lifetime. It can be difficult to acknowledge that without letting it distract from the patient in front of me.

In those moments, I am reminded of an approach emphasized by one of my favorite clinical professors: to meet the patient where they are. This approach starts with assessing the patient’s knowledge and comfort levels and using that assessment to guide our recommendations. It’s muscle memory for seasoned physicians, from whom I have learned to take the extra minute from a busy day to give better patient education, offer alternate medication options or treatment plans, encourage closer follow-up, and engage social support.

Though these are important practices to integrate, I have also learned that these efforts are not a guarantee for success when time, money, energy, and social support are limited. So, when all of those limitations are characteristic of where the patient is, one’s own ZIP code, I wonder: Where is that meeting place and what can it look like?

How do you meet patients where they are? Share your ZIP code findings in the comments.

Dr. Teresa Samson is a second-year internal medicine resident in San Antonio, TX. In her spare time, you'll find her sitting in the sunny corners of the hospital, FaceTiming with her family, and enjoying any excuse to be outdoors. You can follow her journey on Instagram at @residentdoctor_t. Dr. Samson is a 2023–2024 Doximity Op-Med Fellow.

All names and identifying information have been modified to protect patient privacy.

Illustration by April Brust