The National Football League (NFL) kicked off its 100th season on Sept. 5 with a matchup between the Chicago Bears and the Green Bay Packers. The Bears and Packers, two of the league’s most successful franchises, comprise the league’s oldest rivalry dating back to 1921. In a game dominated by defense, the Packers ultimately prevailed 10-3.

Ever since Super Bowl XXVII, in which the Troy Aikman-led Dallas Cowboys steamrolled the Jim Kelly-led Buffalo Bills, I have been hooked on the NFL. Holding as true now as it was in 1993, I find the league’s sheer unpredictability and parity to be riveting. The beginning of the regular season has been an event I have looked forward to every year.

Up until medical school, I found it easy to rationalize my support for the NFL. Of course, I knew that playing football was dangerous. The history of the league is marked by a variety of infamously gruesome injuries, ranging from Joe Thiesmann’s broken leg in 1985 to Destry Wright’s dislocated ankle in 2000, all of which underscore this point. Yet NFL players are generally well compensated and, as adults, are well-equipped to make their own informed decisions.

As I progressed through medical school, I began to second-guess my devotion to the league. For starters, I realized that the risks of playing in the NFL were far greater than I had previously known. The first case of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) in a former football player was reported in 2005, for instance, but the link between football and the neurodegenerative disease was not widely reported on for several more years. Many deleterious health effects likely remain unknown.

I also came to doubt that NFL players could truly make an unbiased decision to play football. The long-term consequences of playing football, which might not manifest for decades to come, might appear remote and insignificant to players in their 20s and 30s in the present day compared to facing the intoxicating prospects of fame and fortune. Not to mention that high salaries might rob players of their agency to make truly informed decisions about putting their lives at-risk.

In recent years, as the long-term health risks of playing in the NFL have become increasingly clear, these doubts have only grown. Repetitive head trauma, unsurprisingly, can result in brain damage that can profoundly affect the lives of NFL players long after they retire. Traumatic brain injuries, for example, can lead to pituitary dysfunction, which can compromise quality of life. A recent study in JAMA Neurology of former NFL players found that those with worse concussive symptoms at the time of injury were more likely to suffer from hypogonadism and erectile dysfunction in later years. Worse, these injuries can ultimately result in neuropsychiatric dysfunction. The younger one starts playing football, the higher the apparent risk: players who begin playing before the age of 12 are more likely to experience deficiencies in neuropsychiatric and executive function as adults.

In the last few years, there has been an increasing appreciation of the risks of developing CTE among football players. First described in boxers as dementia pugilistica or punch drunk syndrome in 1928, CTE is a neurodegenerative disease caused by repetitive trauma to the head. Patients with CTE often experience behavioral disturbances, mood changes, and cognitive impairment, among other symptoms. Several former NFL players who committed suicide in recent years like Junior Seau and Dave Duerson were later found to have the disease.

And NFL players may be uniquely at-risk of dying early among professional athletes. A recent study in JAMA Network Open compared the mortality rates of NFL and Major League Baseball (MLB) players who had played at least five seasons between 1979 and 2013. The study’s authors found that NFL players had substantially higher mortality rates from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and neurodegenerative disease compared to MLB players. “Comparing hypothetical populations of 1000 NFL and 1000 MLB players followed up to age 75 years,” the authors wrote, “there would be an excess 21 all-cause deaths among NFL players, as well as 77 and 11 more deaths with underlying or contributing causes that included cardiovascular and neurodegenerative conditions, respectively.”

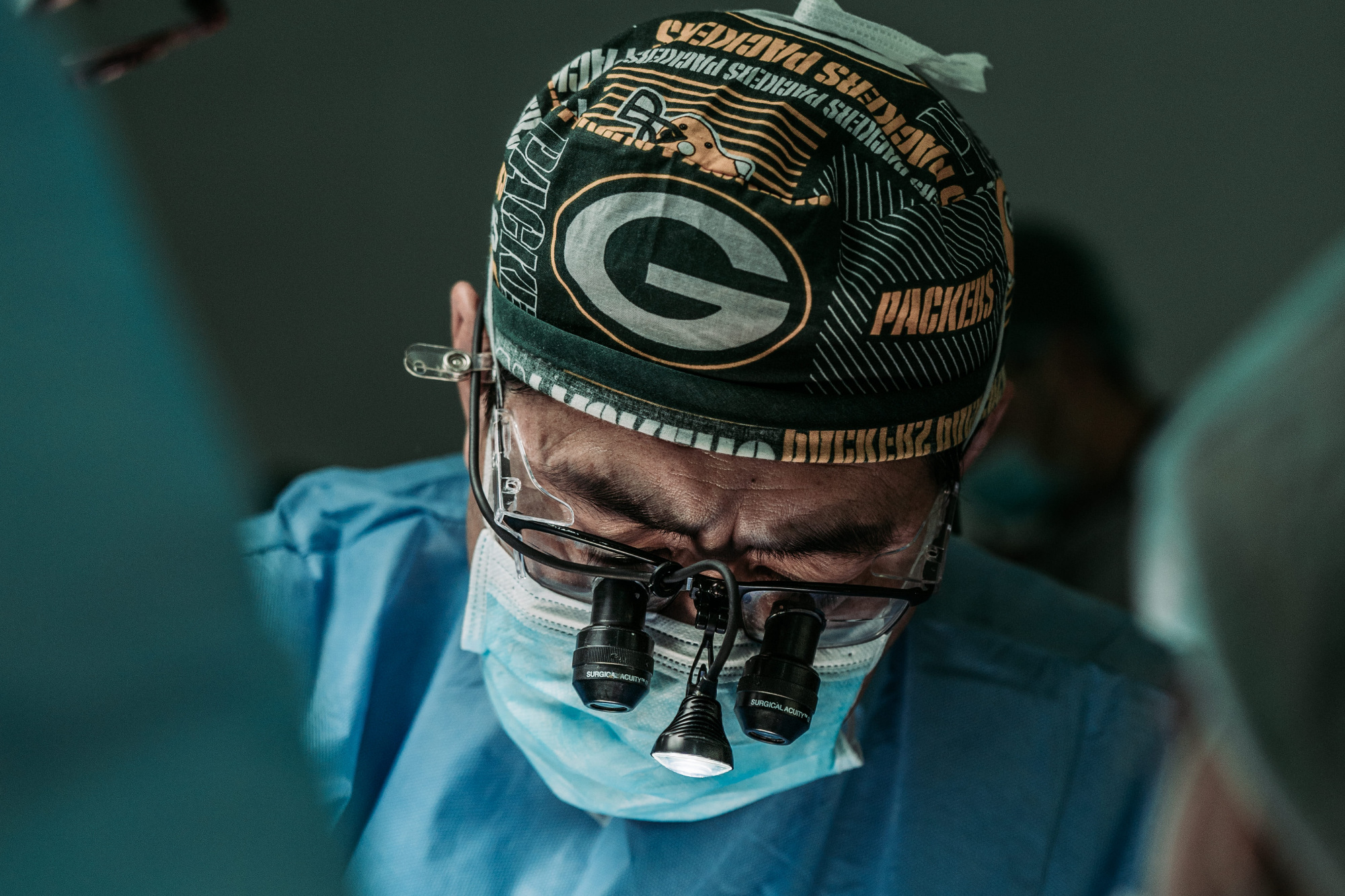

As these findings pile up and as I have progressed through my medical training, I have found myself confronting a number of rather uncomfortable questions. Having pledged to heal the sick, is it still appropriate to revel in a sport that glorifies an organized form of physical violence? If I personally believe that football is hazardous to human health, as the data clearly shows, is it not unethical to watch young men jeopardize their bodies by playing? Finally, knowing what I do about the challenges involved in obtaining true informed consent, is it morally acceptable to support the NFL when I have strong reason to believe that its players do not have a full appreciation of the health consequences awaiting them 30, 40, and 50 years in the future?

It is easier to suppress these concerns than to face them head-on. But as I watched week one of the NFL’s 100th season, witnessing player after player go down with an injury, I could not help but feel guilty.

I do not know if watching the NFL is unethical. But now, more than ever, it has become clear that the sport clashes with the ethos of American medicine.

Dr. Kunal Sindhu is a resident physician in New York City and a 2019-2020 Doximity Fellow. You can follow him on Twitter @sindhu_kunal.

Image: JC Gellidon / unsplash