He started as a special education teacher writing books for special needs children. He was dyslexic and a fantasy novelist. When he started medical school, he thought he would be a pediatric neurologist.

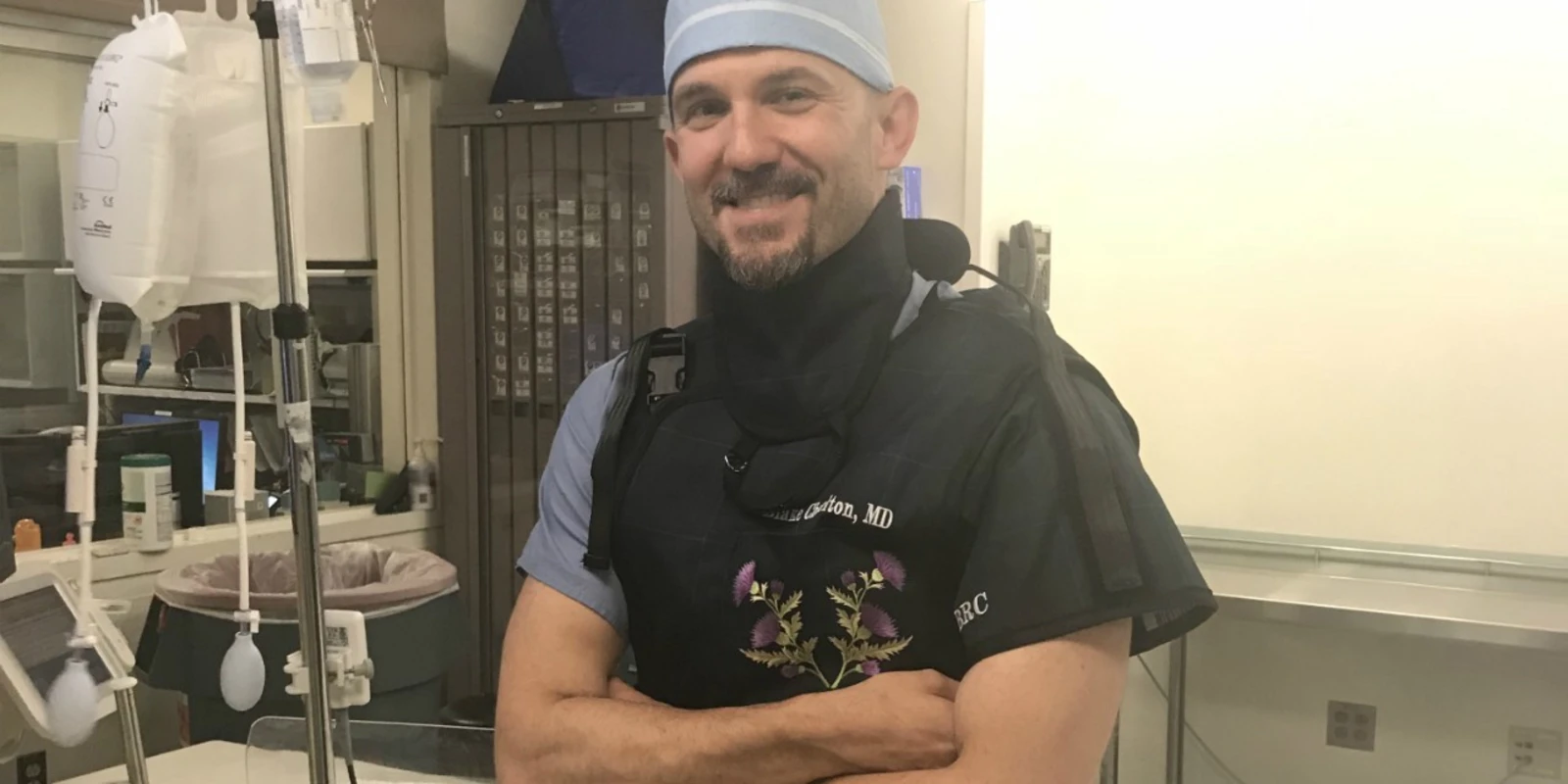

“Which is about as far from adult Interventional Cardiologist as you can be,” Dr. Blake Charlton says.

He was turned on to Internal Medicine during medical school, and subsequently Cardiology, by a mentor, a doctor named Abraham Verghese who is also a novelist.

“I found that I just really liked adults and the physical exam, which Abraham was known for, and Cardiology is something that is very fast-paced and very logical, and you can figure a lot of things out from first principles,” Dr. Charlton explains.

What may have sealed the deal happened when he was a junior resident and saw a woman come into the emergency department who was in a tachyarrhythmia. Other emergencies were transpiring and he was one of the more senior people not occupied. He pushed a drug to return her to normal rhythm and remembers it was “magical” she had been “so precarious a moment before and then now was back to normal health.”

As far as his career goes, Dr. Charlton knows he’s doing things a bit backward. Physicians usually transition into a different career from medicine, not the other way around.

“They say about dyslexics that we do everything backward. (We don’t really,)” says Dr. Charlton. And while there were pros to being a novelist first — “when you’re young you don’t have things pinning you down, and you have a lot of romanticism and optimism and you feel like you have time for everything” — there were cons to starting a medical career second — “it’s a rigorous and demanding medical training, it’s harder working 30 hours in a row (sometimes longer), it gets harder and harder the older you get.”

But writing and medicine do have one thing in common: the pursuit of perfection. A novelist friend told Dr. Charlton to “finish and submit” his writing, something that can’t be done in medicine.

“He [the novelist friend] meant that both in the literal sense of you have to get to the end of a project and submit it, but he also meant commit yourself to getting all the way through and not getting so involved in how wonderful it’s going to be that you keep working on it indefinitely. And then not only send your manuscript off for judgment, but submit because you’re powerless once you’ve created this work, you no longer really control or own it anymore,” Dr. Charlton explains.

But working on something indefinitely is something inherent to medicine.

“You have to continuously push yourself to be perfect and to be the best you possibly can and eternally improve your knowledge, your reasoning, your technique,” Dr. Charlton says. “You must always strive forever to be perfect and you’re never going to submit and send your work out and see how it does.”

Though that pressure to be perfect can be crushing sometimes, the meaning that medicine provides makes up for it. While there is a good chance that even after you create your piece of art that people won’t care about it, any work done as someone in medicine is always appreciated.

“Every day you get up and do something and you know somebody is better off because you woke up that day and went to work. Somebody pointed out to me the pyramid of needs — at the bottom of the pyramid is shelter and food and safety and sleep, and at the top is spiritual purpose and meaning and all the non-essential things,” explains Dr. Charlton. “If you’re a medical trainee, the pyramid is perfectly inverted. There’s an overabundance of meaning, and a romanticism of all the people you try to save — some you can and some you can’t — and yet you often have no idea when or if you’re going to be able to sleep or eat or go to the bathroom.”

Medicine also has an overabundance of people willing to take care of others, says Dr. Charlton. Whether that means appreciating the nurses who have helped him learn technique, familiarized him with procedures, and educated him and other fellows on how to bring a high level of care to the unprivileged people in his clinic, to a patient who had a community rally behind him and show him the meaning of making a difference in the lives of others.

“He was a religious leader and toward the end of his life he was brought in by a different member of his congregation every time he came to see me,” Dr. Charlton remembers. “And through the eyes of the reflection of this community that was helping to take care of him, I really saw how special you could be to somebody.”