I learned to cut when I was Desmond’s age — 5. I failed miserably at first because, according to my kindergarten teacher, my left-handedness was not acceptable, and thus having to cut with my nondominant right hand felt particularly haphazard. Somehow supinating my right hand and supporting it with my left while desperately trying to palm the scissors seemed like the only way to make things work (clearly the Edward Scissorhands of kindergarteners). Eventually, I learned to cut with my right hand the proper way — first and third fingers through the holes — until using scissors became part of the mundanity of muscle memory.

The second time I learned to cut was in my third year of medical school. I watched as the surgeon furiously knotted closed an abdominal wall. Sweat fogged up the plastic mask shielding my eyes, and scissors were somehow in my hands. I had learned to hold the scissors now with my first and fourth fingers through the holes, to support my right hand gently as I moved towards the 1-0 polydioxanone suture, and to slide the scissors down towards the knot, rotate them 45 degrees, and cut.

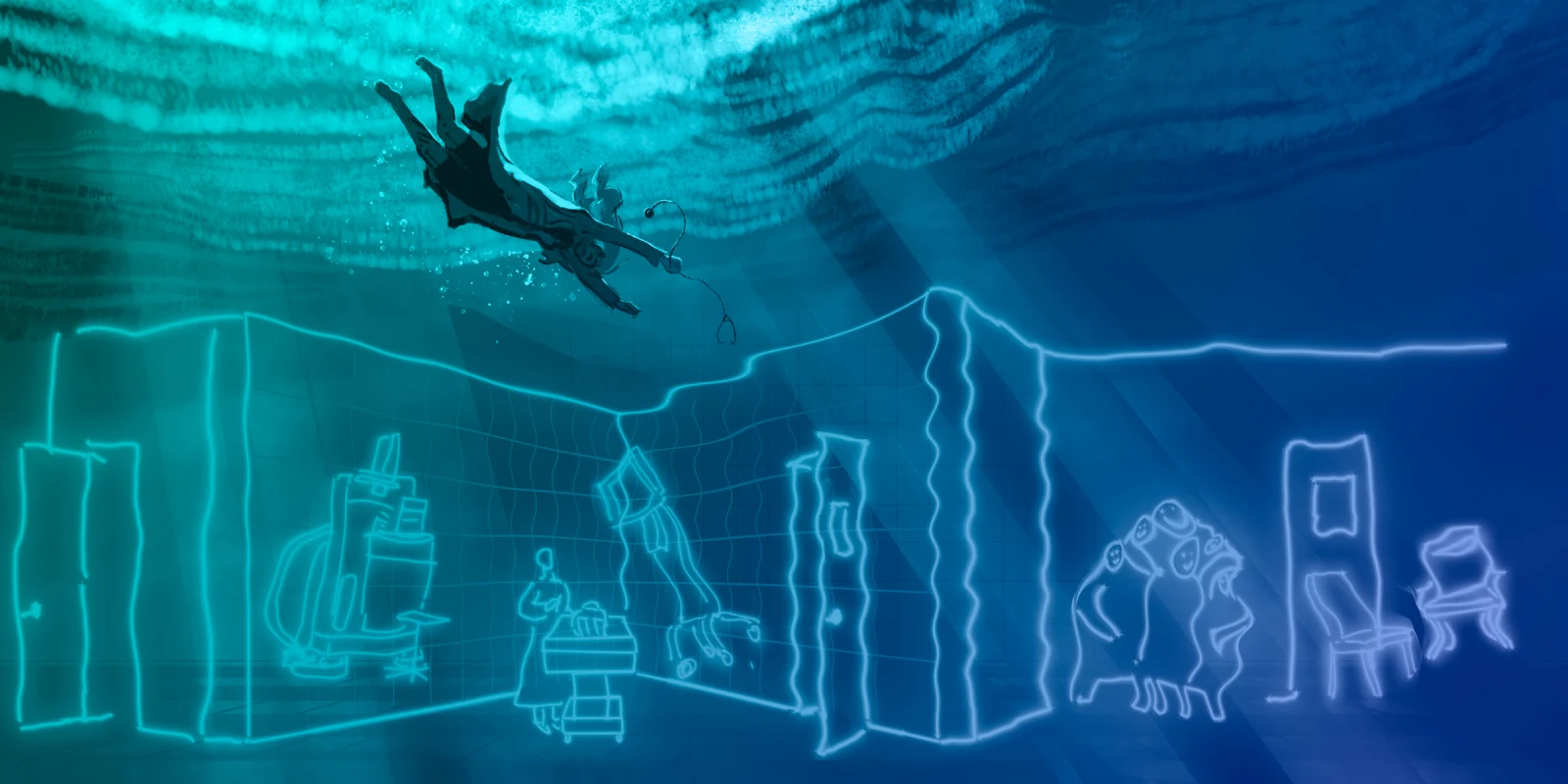

Desmond is the first child I saw die. When I met him, I had just got off an early morning flight from Washington, D.C. to somewhere in Missouri, and his face was hidden by blue drapes pinned up to IV poles. All I could see was a circle of brown skin glazed golden with iodine, encompassed by more blue drapes. After we (the surgical resident, the attending surgeon, two other doctors from a hospital in Georgia, and I) scrubbed in for the case, a nurse read something aloud about Desmond written by his family. He liked eating, dancing, and, tragically, swimming.

Then we cut the abdomen and then the chest. I watched the heart move to the beeping of the monitor, the sound holding together tiny Desmond’s life. When the surgeon allowed me to feel its beat in my hand, I felt like I was violating the sanctity of life, and yet I did not want to pull my hand away. Meanwhile, my team worked inside the abdomen, dissecting away fascia, omentum, and mesentery, cauterizing bleeds, and mobilizing the organs.

I imagined him drowning. Perhaps in the pool of a family friend at a birthday party while mothers and fathers mingled inside, prattling away about the latest happenings. They thought he was just holding his breath. You cannot swim without coming up for air, someone teased.

Procurements begin like any other surgery. You protect the organs and tissues, bleeding is stopped and the organs must stay well perfused. All the same rules apply: the OR team is concerned with the patient’s blood pressure, heart rate, and oxygen saturations — the vital signs. But the end of the surgery is extremely different.

The doctors from Georgia working in the chest clamped the appropriate arteries, positioned the cannulas, and cut out the heart. It happened fast, as I had imagined an ancient ritual would have. The blood ran red, and I stood there dutifully suctioning it away, while my team packed ice into the body cavity. For preservation, the organs were flushed with countless liters of a cold chemical solution until the blood left the body and all that was left to suction was clear fluid.

Maybe it was in the river. The great old Mississippi. He was swimming with his older brothers and waded in too deep in an attempt to avoid the sticky Missouri heat. They made him use goggles, but the pressure on his face was worse than water in his eyes. You cannot swim without coming up for air, someone teased.

The anesthesiologist had silenced the heart monitor. It had to be sometime before they took the heart, and I never heard the persistent monotone flatline that we so often associate with dying, a sound I had only heard in movies. I knew that Desmond was dead, but the bustle around his body indicated otherwise. I could not accept his death. A child had died, and yet I knew that the very purpose for which he was in our OR was to die and to die carefully. His brain died when he drowned. Logically I knew this. It was why nobody could take his lungs — too waterlogged, too damaged.

Wherever he had been, his arms focused on beating through the soft water. But eventually, all the thought and energy that went into staying afloat — measuring the weight of the water around his body and maintaining proper arm movements — failed. He loved swimming. Paramedics came, but the brain can only be deprived of oxygen for so long. There was a prolonged resuscitation — many rounds of CPR and epinephrine, and finally, the return of spontaneous circulation. His body saved but not his being.

Once we finished flushing the organs — the stomach, small intestine, pancreas, and liver — we removed them from the body cavity en bloc. The doctors from Georgia had already left with their heart, and we prepared the kidneys for another team. The lungs were left behind. We closed him up quickly, returning to Washington, D.C., where another little boy, only 9 years old and terribly sick, slowly dying, was already asleep on the table, waiting for his borrowed organs to bring him new life.

That night was a cycle and a reminder that hospitals are places of power and resilience. Death in a hospital, at least to those of us who work there, is commonplace, but so is new life. We sometimes forget how much of a privilege it is to experience life and death side by side every day, where one child’s heart is both an ending and a new beginning, tragedy for one family and joy for another.

We are there for many moments like these, where people are their most vulnerable and scared. These moments are critical. They are the humanity in medicine — life, death, and what lies in between.

Have you encountered critical moments in a clinical setting? Share your experiences in the comment section below.

Caitlin Cain is a fourth-year medical student at Georgetown University in Washington, DC. She is an aspiring general surgeon and is interested in medical humanities as a means for enhancing clinical practice.

All names and identifying information have been modified to protect patient privacy.

Illustration by Jennifer Bogartz