A post from an old college classmate recently came across my Instagram: after four years of medical school, five years of residency, and one year of fellowship, he had just taken his first attending job as a trauma surgeon. I hadn’t seen him since our college graduation in 2009. It made me think back to that dizzying weekend of ends and beginnings. Many of my classmates were off to graduate school, business school, law school, medical school. Some were starting jobs in New York City, not far from our campus in suburban New Jersey. I was off to the other side of the planet, to teach English for a year in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. It was a place I had never been and could barely identify on a map. As many of my friends headed down well-defined paths, I was ecstatic to be stepping into the complete unknown. It wasn’t that I had no idea what I wanted to do with my life — it was that I had too many.

That hadn’t always been the case. As a child, I loved reading, writing, and drawing. I aspired to be a children’s book author and illustrator when I grew up. My father is a perinatologist, and medicine was always in my peripheral vision — the background to my experiences but never the focus. I loved my science classes in high school, but a career in the sciences didn’t cross my mind. I chose my undergraduate institution for its creative writing faculty, and couldn’t wait to embark on my dream job of being a writer.

The first wrinkle in that plan came the summer before college. I spent it living with my dad, and during those months, I started accompanying him to the hospital. In a pair of blue scrubs, I followed him and his colleagues into patient consultations, stood at the foot of the bed in delivery rooms, had my own spot at the operating table. I will never forget what it felt like to pin a plastic bucket to the end of a hospital bed with my hip, massaging a woman’s abdomen with one hand while gently tugging the end of the umbilical cord with the other, watching as the placenta, slippery and steaming, slid into its target. The heady combination of bleach and blood in the OR, the thrill of watching a tiny head emerge. Those brief but rich experiences on Labor and Delivery instilled in me an awe for the human body, and introduced a pesky voice that asked: What about medicine?

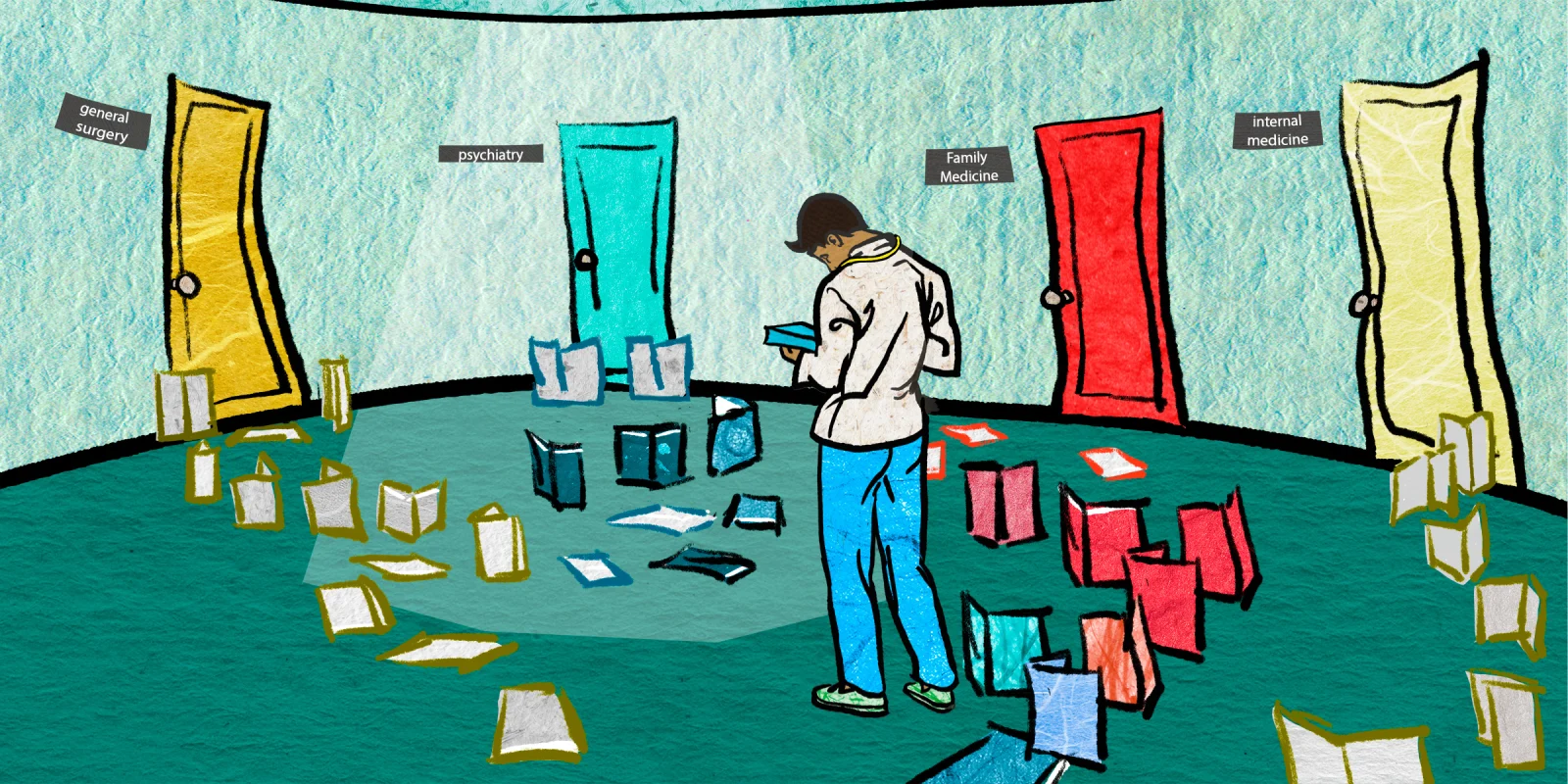

I started college feeling very confused. What if … I did want to be a doctor? I attended my institution’s pre-med information session, hoping for clarity. The clarity I came away with was that I simply wasn’t willing to spend at least half my time in college taking courses that were required for a career path I was intrigued by but by no means committed to. I pushed medicine to the back of my mental Options for the Future shelf, knowing I could always come back to it if I wanted to. I dove into foreign languages, literature and poetry, studied abroad in Spain, and invested deeply in my campus community, becoming an active leader in my school’s outdoor experiential education program, as well as an LGBTQ+ student advocate. By the time graduation approached, there were many things I could see myself committing my life to. Writing? Education? Advocacy? Travel? … Medicine? The only thing I was sure of was that I wasn’t sure. I packed my bags for Indonesia and hoped I would figure it out.

And gradually, over the next six years, I did. In Indonesia, I realized that I loved education, but that I also wanted a concrete skill set I could use to tangibly help other humans, anywhere. I returned to the U.S. to take a job with the small nonprofit fellowship organization that had sent me to Indonesia, which took me many different places — into New York City board rooms, Burmese newsrooms, Mongolian classrooms, and, eventually, to Singapore, where I lived and worked for several years. Along the way, I met my wife and we had our first child — and then our second, and then our third. The experiences of being pregnant and giving birth finally solidified my aspiration to learn medicine, but the road was still long: it took a year to apply to a post-baccalaureate pre-med program, and then two years to complete it, before I could even apply to medical school. My college classmates are attendings now, and I am here: a 33-year-old second-year medical student and mom of three. I have never felt more sure.

Although many medical students take one or two “gap years” between graduating from undergrad and matriculating in medical school, my experience as a non-traditional medical student is fairly unique. According to data from the AAMC that tracked the age of applicants to U.S. medical schools from 2014–2018, the average age of medical school matriculants held steady at 24 years. Interestingly, for each of the four application cycles during that period, the average age of medical school applicants who did not matriculate was higher than for applicants who did matriculate across all demographic groups, suggesting that older applicants have not been matriculating at the same rates as younger applicants. When the AAMC published new applicant data on their Medical Education FACTS website in 2019, it noted that the specific table of data that tracked applicants’ ages had been removed due to “low usage.” There doesn’t seem to be much attention given to the age, and corresponding life stage, of medical students, and the important experiences that those in different life stages might bring to the table — but there should be.

Medical students who are older, who have had previous careers or have simply navigated more of life’s twists and turns, bring a unique set of skills and strengths to medical education (and to future practice), which are well-matched to the profile that medical schools are seeking. The AAMC’s Core Competencies for Entering Medical Students describes 15 competencies in the categories of Interpersonal, Intrapersonal, Thinking and Reasoning, and Science. Of the 15, only two fall in the Science category, and the category with the largest number of competencies is Interpersonal. Of course, students who are transitioning directly from undergrad to medical school, or who are in their early 20s, can demonstrate service orientation, social skills, cultural competence, teamwork, and strong oral communication — but non-traditional students have often lived these competencies with a depth and nuance that only time can allow. In my view, medical students who have had to navigate the dynamics of a workplace, who have switched careers or had to manage up, who have learned to balance a full-time job with full-time diaper-changing, bath time, and meal prep, who have been responsible for the education, development, livelihoods or even lives of other humans, are stronger students for it. They will certainly be stronger clinicians for it, too. Non-traditional students have a range of experiences and a well of resiliency that we bring to our colleagues and our patients in the forms of maturity, empathy, emotional intelligence, adaptability, and endurance.

Perhaps most importantly, we’ve chosen this. Rather than being swept along by the natural momentum of years of education that propel many traditional students forward, many non-traditional students have reversed course and swum against the current to be here. As Dr. John Schriner, the associate dean for admissions at Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine, advises college students considering going directly to medical school: “Make sure you know in your heart of hearts that this is what you want to do [and] that you are prepared to fully commit yourself to this … And do it for the right reasons.”

The choice to give up a career and return to a grueling program of professional education (that could take 10 years or more) is rarely made on a whim. Medical schools should recognize the skills developed in previous careers, and the character traits honed over additional years of life experience, as unique strengths. They should seek out non-traditional students. When admissions committees take stock of the extra time we took to get here, I hope they see it for what it is: proof that we are all in. Non-traditional medical students know, in their heart of hearts.

By the time I’m ready for my first attending job, I’ll be 40 years old. But what I will miss in additional work years, I feel confident I will make up for in what I bring to my patients: the perspective, sensitivity, and understanding gleaned through having lived those years. I’m all in.

Fiona Miller is a second-year medical student at the University of California, San Francisco and the mother of three feisty kids. She is passionate about racial health equity, reproductive justice, and harnessing the power of human stories towards healing. Fiona is a 2020–2021 Doximity Op-Med Fellow.

Illustration by Jennifer Bogartz