If you have ever taken a course in basic life support (BLS), you likely recognize the face of the CPR doll affectionately called “Resuscitation Annie.” The ubiquitous visage of the doll was modeled after L'Inconnue de la Seine, an unidentified woman whose body was removed from the Seine River in Paris around 1880. Though her exact cause of death remains unknown, the pathologist who performed her autopsy was so fascinated by her peaceful expression that he enlisted the help of a mouleur, or molder, to capture her countenance in wax. Philosophers have even referred to the young girl as medicine’s Mona Lisa, owing to the similarity of their enigmatic smiles. Ironically, if you have ever provided basic life support, you probably would not use the word “peaceful” to describe the scene.

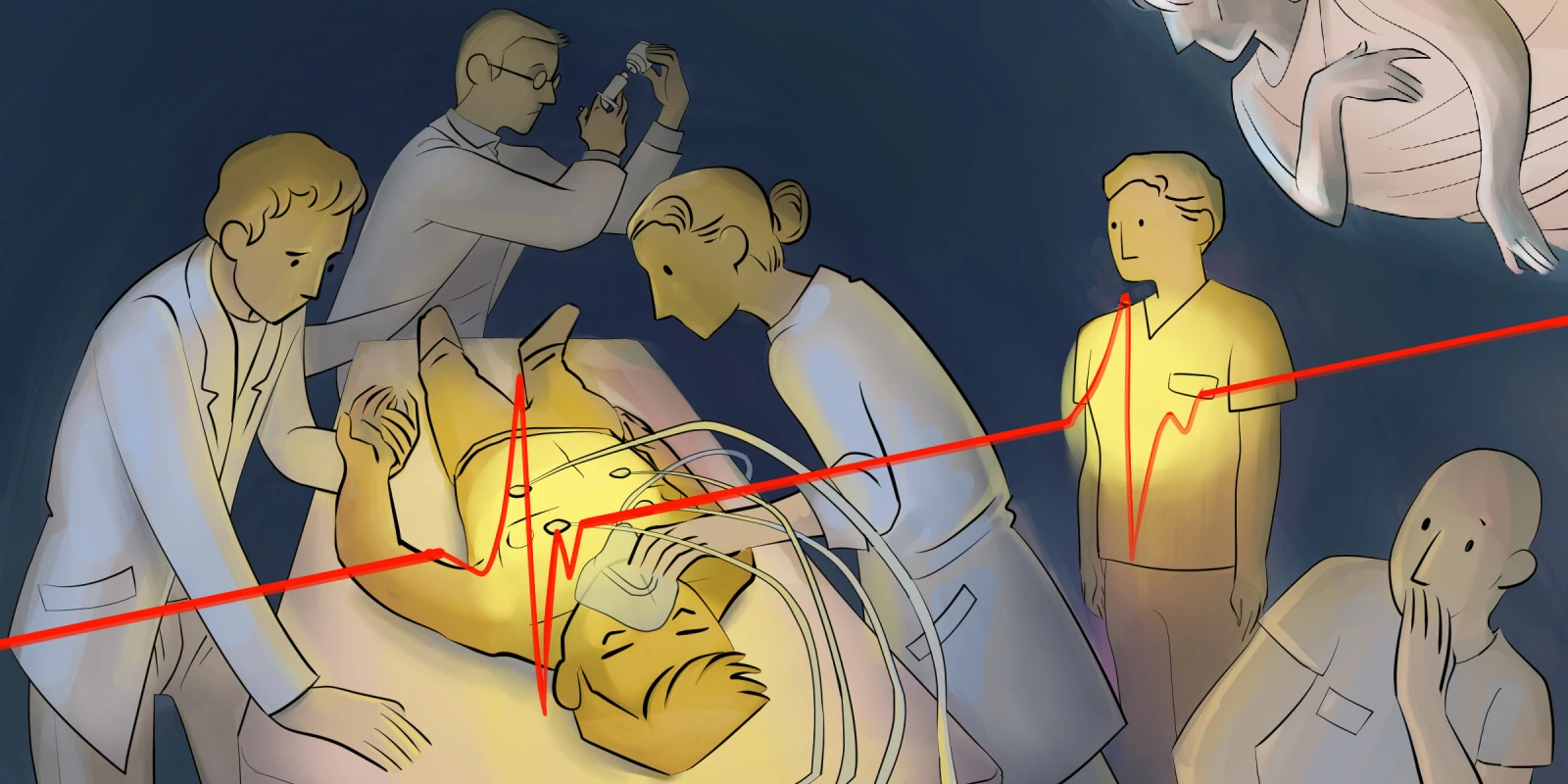

No BLS certification course could have prepared me for the brutal, almost violent feeling of resuscitating a patient. I could feel my heart anxiously pounding in my chest as I rhythmically performed compressions. The automated external defibrillator, or AED, would periodically announce “good compressions,” but what I was doing felt far from good. Each time I forced my body weight down through my hands, there was an agonal breath followed by the sputter of blood from the patient’s mouth. There was no serenity in that room, much less a smile.

When the physician leading the code finally announced the time of death, I felt a peculiar sense of relief. Despite the knowledge that we were trying to save someone’s life, the experience looked more like torture than treatment. Leaving the surgical ICU, I felt a profound emptiness. Not only were we unsuccessful, but I feared we had brought unnecessary trauma and suffering to the end of this man’s life.

As I walked back toward the work room with my fellow third-year medical students, the senior resident sensed our disappointment at the outcome and reassured us that we should not hang our heads in shame. Gentle yet honest, he reminded us that life-saving measures are not always successful, even within the confines of the hospital, and they are certainly not glamorous. Being careful not to minimize what we had just been a part of, he emphasized the delicate balance between two pillars of medical ethics: beneficence and nonmaleficence. As much as it was our moral duty to try to keep that patient alive, it was equally essential that we knew when to stop.

Up to this point, my experience with medical ethics had largely been limited to the theoretical. Practice questions and patient vignettes did their best to exemplify the core values of medicine, but they were binary, incapable of capturing the complexity and unpredictability of medicine. First-hand experience allowed me to understand that fulfilling our ethical responsibilities requires acknowledging our limitations and accepting the reality that decisions are rarely black and white. It is easy to select the best next step in a multiple-choice scenario, but making these decisions during a high-stakes scenario is far different and requires a deep understanding of both medicine and the human condition.

Driving down the highway that evening, I thought back to the sights and sounds of my first code blue, troubled by the patient’s less-than-peaceful death. I kept picturing the expression on his face, lamenting the circumstances of his passing. Since then, I have continued grappling with what it means to “do no harm” when medical advances continue to push the boundaries of what is possible. In the world of medicine, we share an innate desire to heal and preserve life. It is a calling that drives us to push the boundaries of medical knowledge and innovation. However, amid this pursuit of healing, there exists a profound and often overlooked truth — that sometimes, healing must come in the form of letting go.

What truths about medicine have you learned from high-stakes scenarios? Share your comments below.

Jacob Herstein is a fourth-year medical student in Galveston, TX. He enjoys basketball, reading, and taking his dog to the beach. He tweets @JacobHMed. Jacob was a 2022-2023 Doximity Op-Med Fellow.

Illustration by April Brust