I am sitting in my primary care office exam room facing my patient. As one of my routine questions, I ask whether she has an advance directive. In a not so uncommon manner, I hear a defiant response: “My family knows to pull the plug!”

In my head I ask, “But do you even want to get plugged in?”

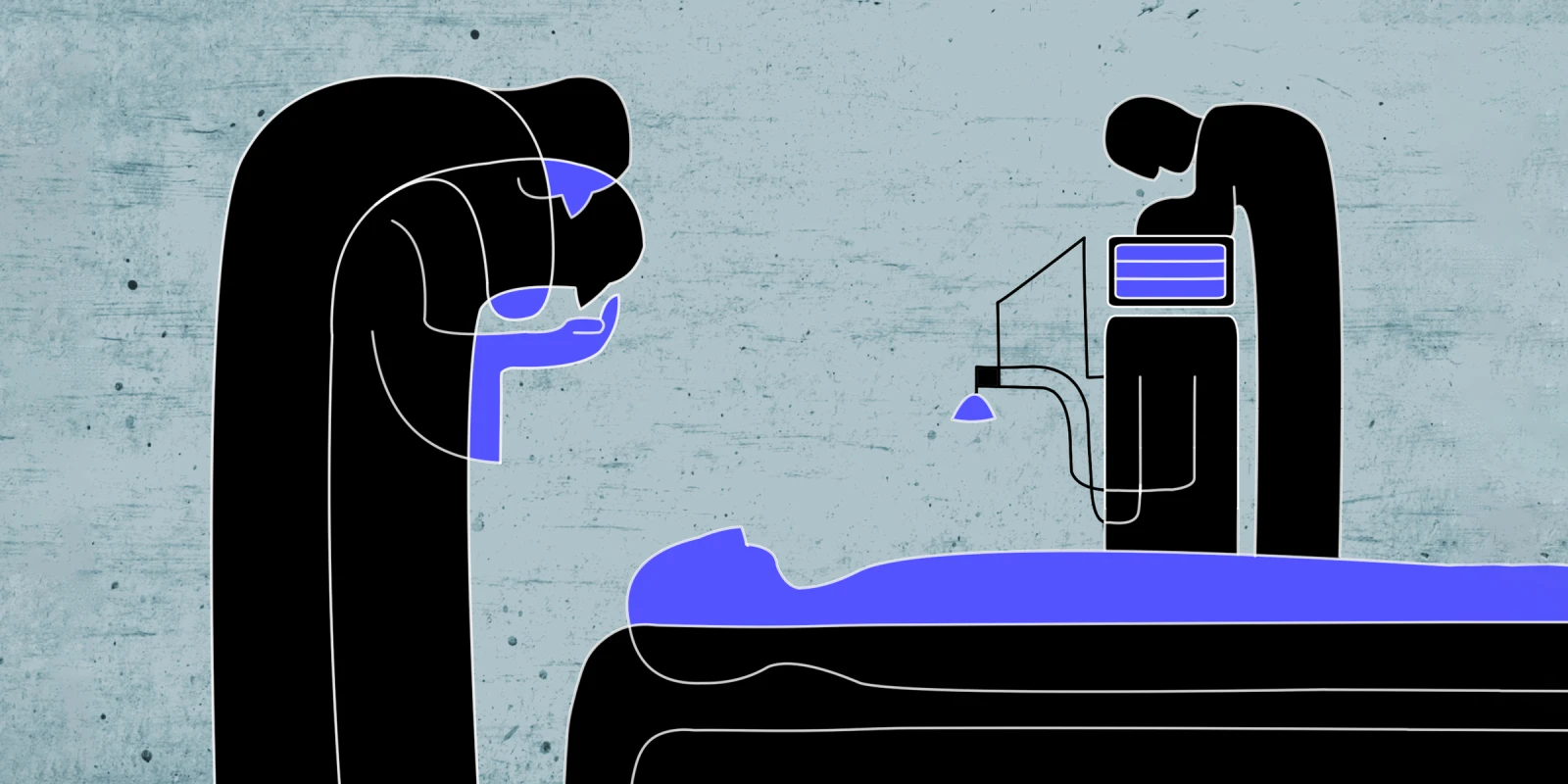

My mind flashes back to a moment during my days caring for patients in the hospital ICU. The hospital room is large with white linoleum floors, white walls, white ceiling tiles, and accents of medical blue. The smells of light bleach and single-use plastics fill the air. The room is crowded with medical equipment: an overbearing ventilator rhythmically humming, towers of infusion pumps providing IV fluids, big and small monitors beeping and flashing warnings.

In the center of it all is an 83-year-old human being. He is seemingly tiny, tucked into a hospital bed under layers of thin white blankets. He is sedated and tethered to pumps and monitors by IVs and wires and, most notably, an endotracheal tube that enters through his mouth connects his lungs to the ventilator.

The patient suffered a myocardial infarction with cardiac arrest at home a few days ago, and although CPR has successfully restored circulation, he has not regained any meaningful function. He will not make a recovery.

Today, several members of his family surround him for the planned terminal extubation. During this final procedure, he will be removed from the ventilator and monitored until his last breath.

In these scenarios, if the family is not confident of the patient’s end-of-life wishes, the decision of when to “pull the plug” and withdraw care becomes one of the most difficult to make. It always feels too soon. There is always the hope of a miracle.

So, what if we rewrote history a little? What if this man had had the myocardial infarction at home, but in his older years had created an advance directive with his physician, including a DNR order? Instead of leaving decisions to the medical dominoes of CPR to ICU, what if he had declared he wanted to pass away as nature intended and on his own terms? In essence, what if he never got plugged in?

As physicians, we often avoid the conversation with our older or sicker patients: “You’re less healthy than you used to be. You’re not as tough. You’re more likely to have a bad outcome from an attempted resuscitation.” We avoid this conversation because it is time consuming and underreimbursed. As a family physician in primary care, I fully understand the constraints. However, I also recognize that the underlying reason we often avoid this conversation with our patients is because we, too, are uncomfortable having these discussions.

Patients come to physicians for our expertise. And one of the areas in which we have far more experience than they do is recognizing death. We see it looming for our sicker patients and can sense when it approaches; perhaps these patients have been admitted to the hospital several times in the past year, or have a diagnosis with a poor prognosis, or have multiple chronic conditions at an old age. In a wrestling match with death, we know which patients stand a chance and which are likely to lose. They, on the other hand, likely have not been down this path before and might not even realize they need a guide.

The process of becoming dependent on life support is not a singular event. It is a cascade of medical decisions that begin in someone’s living room and then carry over to an ambulance, to the hospital, and ultimately, to an ICU. With an advance directive, patients can decide at which point along the cascade they would like to exit and allow their body to run its natural course. They may choose to ride the cascade until the end, but it should be just that — an informed choice.

It is up to physicians, especially those of us in primary care, to initiate these end-of-life conversations and provide the resources for creating a thoughtful advance directive. With even brief discussions that inspire patients to talk to their families, we can ease so much potential suffering that comes with the uncertainty of making these decisions for someone else. We can reduce invasive medical interventions and give families confidence in their decisions.

Your patient might tell you their family knows to pull the plug, but that patient might also want to consider sparing their family from having to make the difficult decision during a trying time.

An advance directive is one of the greatest gifts a patient can leave their family members near the end. And who better to guide the patient through creating an advance directive than their physician?

Share your experience having end-of-life conversations with patients in the comment section.

Eleanor Tanno, MD, is a practicing family medicine physician in Rockville, Maryland. She grew up in Bethesda, Maryland and stayed locally for medical school at the University of Maryland. She paints semi-professionally with oil and gouache paint, often showing and selling her work. She has a 1-year-old daughter and frequently states that she didn’t know she could love that baby so much.

Illustration by April Brust