Sitting in the empty second chair, the one in the room that is meant for observers, is an uncomfortable position for most physicians. I recently found myself there, an onlooker of our craft. Having newly become a primary caretaker of an aging parent, I sat watching as the pleasant assistant who had just ushered us into the room took my mother’s blood pressure. My mind could not stop itself, though, from quietly tallying the potential flaws. She just sat down. Her ankles are crossed. She’s talking. Her arm is unsupported. I quieted myself.

“144/82, that’s a little high, Mrs. M.,” the assistant says. “Have you been taking your medicine?”

“Yes, I take my pills every day,” Mom proudly replies.

“Great, we’ll recheck that later,” says the assistant. My mind sighs, “OK, good.” Once she leaves, I gently guide Mom through improvements for the next measurement: don’t talk, uncross your legs, etc.

The youthful cardiologist enters the room with admirable promptness and warmly greets Mom.

“Ms. M., it is good to see you again.” Stationed at his computer, I listen as he reviews a short list of follow-up questions while scanning her chart.

“Your blood pressure is higher than we’d like it to be today. Has it been high at home?” he asks.

“Well,” Mom says, “I don’t check it every day. I check maybe a couple of times a week. Sometimes it is good, and sometimes a little high, like 140.”

“Ok. Let’s add a third blood pressure medicine, spironolactone,” the cardiologist says. “I’ve sent it to your pharmacy. We’ll see you back in a few months,” he announces as he turns to leave.

Mom responds with an unsure “OK” and glances at me. My brain screams, “WAIT!” I have little reassurance to offer her as I am confused, too. Did I miss the exam and the follow-up blood pressure? I replay it, realizing the cardiologist wasn’t wearing a stethoscope.

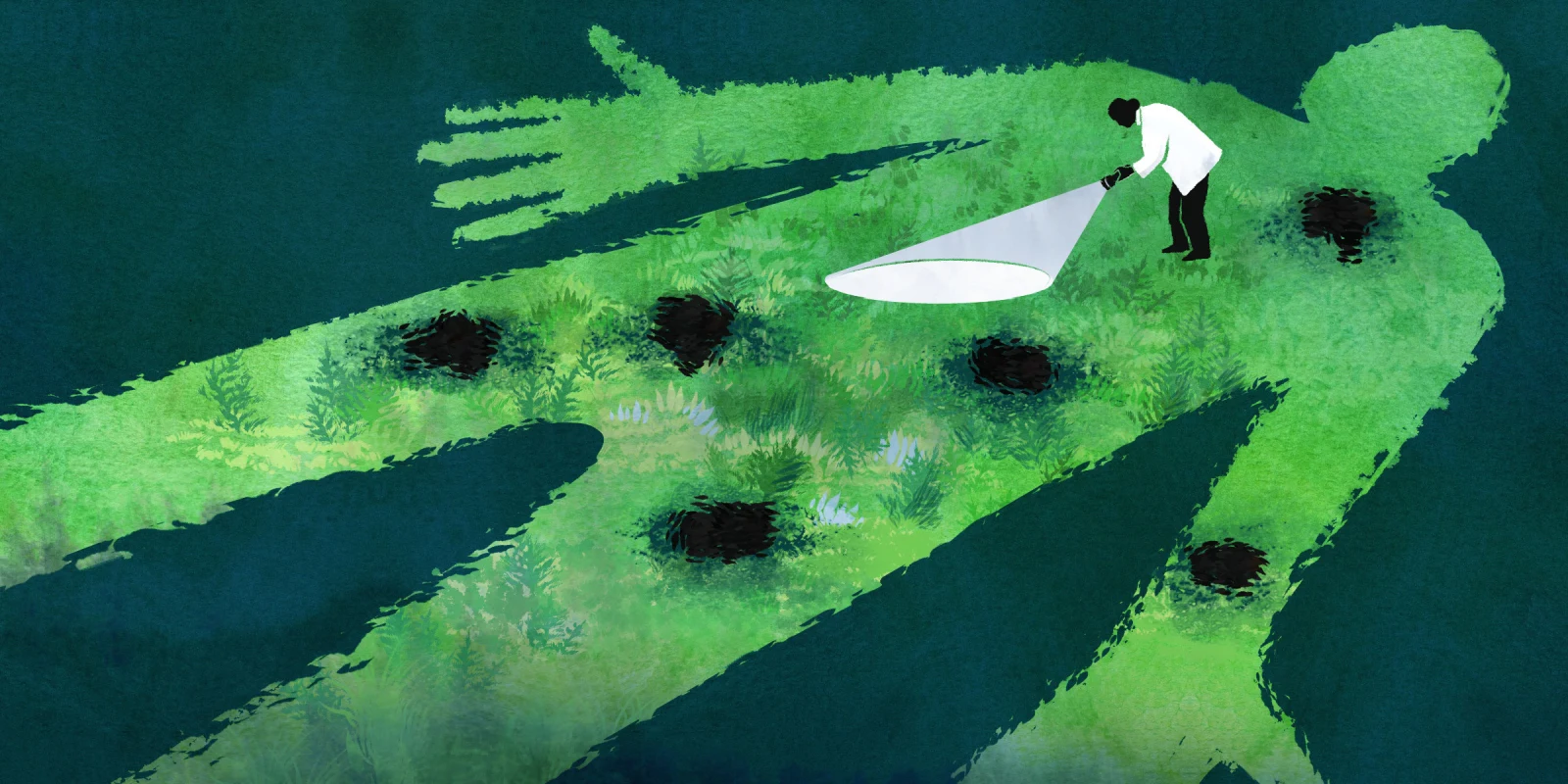

My recent experiences observing medicine from the other side of the exam room left me asking an unexpected question: has the physical exam become an outdated relic? Similar stories shared with me support the idea that skipping the physical exam is becoming a common practice. Is it necessary for dermatology to examine the skin rash, gastroenterology to palpate the spleen, and cardiology to listen to the heart? One could argue that a physical exam is unnecessary for stable patients at follow-up visits. But what if, like in my mother’s case, there is a potential worsening in a chronic condition? Should an exam be done before adjusting prescriptions or ordering tests? What about new patients? Many people seeking face-to-face care may expect or desire a clinician’s touch. Are patients harmed when a physical exam is not done?

Medical dissection to acquire knowledge of the human body is believed to have originated in Egypt in the 4th century. Much later, in the 13th century, texts on accurate human anatomy were published for educational purposes. The discovery of percussion in the late 17th century and auscultation via the invention of the stethoscope in the early 19th century led to rapid development in physical diagnosis. By the late 1800s, a growing understanding of the connection between anatomy and the physical exam revolutionized medical education, solidifying the modern physical exam. The clinical exam thus became a hallmark of improving the accuracy of diagnosing diseases in the modern era of medicine.

In medical school, we are taught that taking a complete history and performing a thorough physical exam are core skills of a good clinician, and essential to master before ordering lab work or imaging. In past decades, upward of 80% of the time, these two steps alone could yield an accurate diagnosis. Evidence suggests that the practice of clinical skills is declining, especially in the U.S. The reasons for the decline are multifactorial. One reason is that clinicians are afforded less and less time at the bedside with families, which impacts the number of clinicians willing or able to teach and the time available for those learning. Increasing reliance on advanced medical technology also plays a role. The two years of social distancing brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic further depleted the value of the physical exam. It is now standard practice for some clinicians to skip the physical exam entirely. As the regular practice of physical examination skills fades, learners will be taught tfewer hands-on skills at the bedside, resulting in a generation that has not mastered the physical exam acumen fundamental to the practice of medicine. Does it matter? Has access to an expanded panel of diagnostic tests and modern imaging made expertise in patient examination superfluous?

A well-known connection exists between incomplete medical exams, diagnostic errors, and adverse events. Skipping to the answer via diagnostic tests results in higher medical costs and may lead to delayed, incomplete, or inaccurate diagnoses. Omitting the physical exam can have potentially life-threatening consequences, including the application of potentially harmful and unnecessary treatments. If not addressed, this can erode the positive patient-clinician relationship, a partnership that produces better health outcomes.

Much of medicine is out with the old and in with the new. Significant medical advancements in the past 20 years, including continuous glucose monitoring, biologics, regenerative medicine, and targeted gene and cancer therapies, all exemplify the positive improvements that modern medicine has brought. Yet, I caution against a move too far away from the bedside. The physical exam is still essential to high-quality patient care. We need all of our senses for accurate diagnosis. Seeing a patient pale, smelling acetone, hearing asymmetric wheezing, and touching the rash all provide invaluable information. Does the patient grimace or wince when you touch their abdomen? Is the spleen enlarged? Our exam guides what additional data may aid in accurate diagnosis. Modern imaging and labs don’t give the whole picture. Tests require our expert interpretation. They should serve as an extension of us, carefully reviewed by clinicians to ensure they match the patient, as they too can be wrong. Ultimately, the results of a physical exam are not only faster, but they are also less expensive.

The benefits of examining patients do not end there. Many studies have shown that touch promotes mental and physical well-being. Physical touch increases feelings of trust, reduces stress, and lessens feelings of loneliness. Researchers found no difference in health benefits in adults when comparing touch applied by a familiar person or a health care professional. For all these reasons, we should teach and perform exams. I am grateful to master physicians like Dr. Bo, who, in his 80s, was still volunteering to precept residents in our continuity clinic. Only at the bedside will residents learn Dr. Bo’s thoughtful approach to the physical exam, gaining the exposure needed to become a steady pair of competent hands. Web searches, social media posts, and expanding technologies threaten our role as healers in the eyes of both patients and institutions. The physical exam is rapidly becoming a lost art, and it is ill-advised that we allow its demise. Let’s reclaim it while we can.

Do you still conduct physical exams in your practice? Why or why not? Tell us in the comments!

Dr. Nicole Hight is a practicing pediatrician in the Atlanta area and a multi-year recipient of the Top Doctor and Parent Magazine parent choice awards. She earned her undergraduate and medical degrees from Emory University and served as Chief Resident at Levine Children's Hospital. She believes a listening ear and an encouraging word changes lives. You can reach her on LinkedIn at www.linkedin.com/in/nicolebhightmd; on Instagram @yourtrustedpediatrician; and on TikTok @doctorhight. Dr. Hight is a 2024–2025 Doximity Op-Med Fellow.

Illustration by April Brust