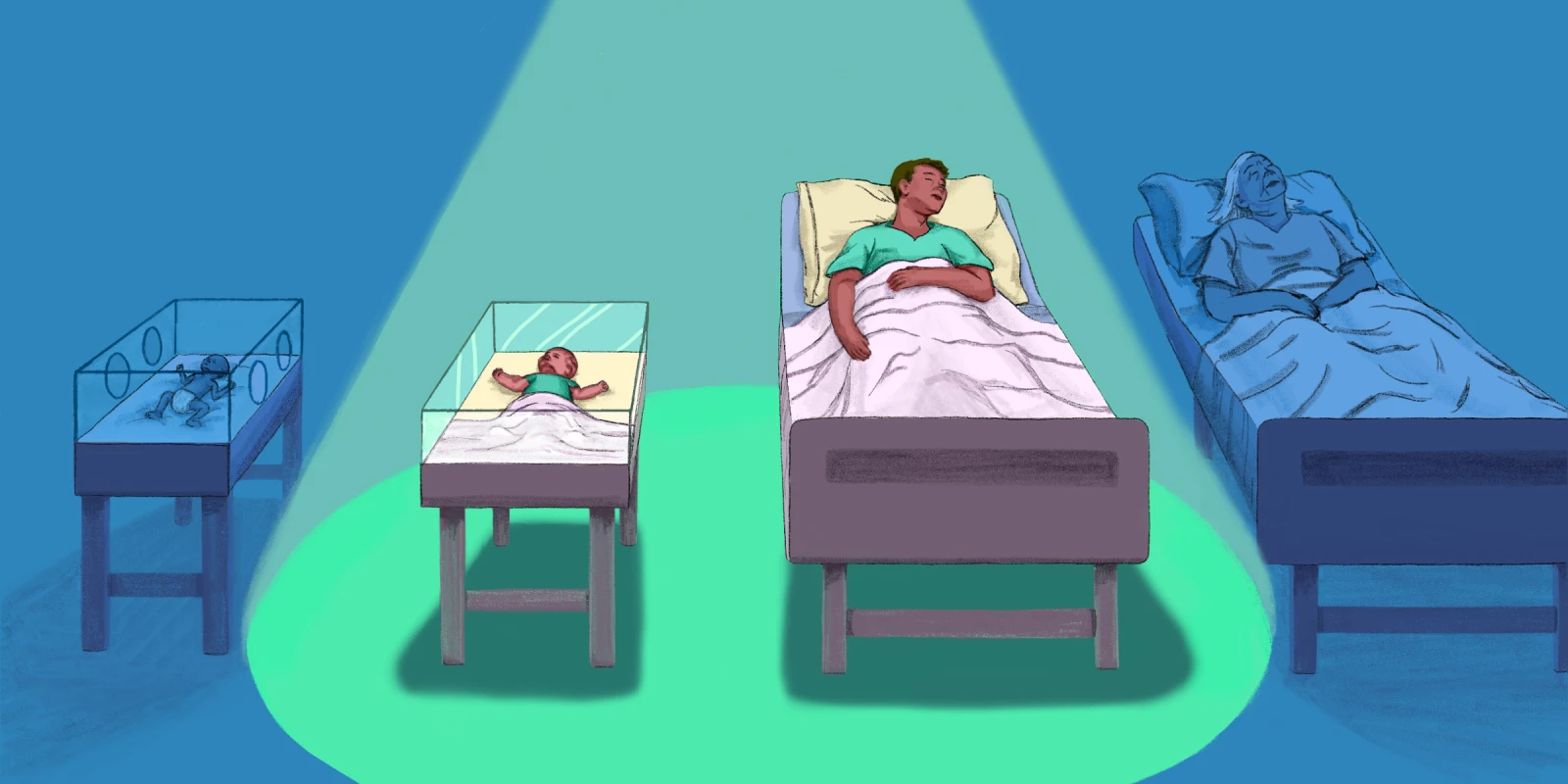

Imagine four patients: an 80-year-old, previously demented person with a new stroke; a 50-year-old with injuries from an automobile accident; a two-month-old baby with meningitis; and a newly born, very preterm infant. Now imagine that each of them has a 50% chance of survival and a 25% chance of significant neurodevelopmental impairment if they survive — reasonable percentages in those situations. Should all of these patients be resuscitated? Would you agree not to resuscitate any of them if family members asked you not to?

Physicians posed these questions in a 2008 research paper and found that more people were willing to not resuscitate the elderly person and the premature infant than the other two patients. Perhaps we are not surprised by the result. But is it right?

I suspect that many agree with not resuscitating the elderly man. After all, he has lived a long life; why risk having him finish his life with even poorer quality than before from a new stroke? It gets a little trickier, though, when we consider whether clinicians should offer treatments like chemotherapy and cardiac bypass surgery as readily to the elderly as to younger patients. Willingness to offer such therapy should depend on statistics showing the effectiveness and safety of the procedure or medications and, if possible, should be discussed with the patient and their family. I suspect this is done in most cases. Care of the elderly is not my specialty, but I wonder if most physicians hedge the discussion in one way or another based on the patient’s age, and if family members change their view based on the patient’s age.

I am personally more familiar with the other end of the age spectrum, the premature infant. In the hospital where I practiced as a neonatologist, we offered parents who were about to deliver a baby at 23 weeks gestation, when the survival rate was about 40%, the option of not resuscitating that baby, which meant that the baby would surely die. In some other hospitals, parents are offered that choice at gestational ages where the survival rate is even greater than 40%. In our hospital, parents rarely accepted that choice, overwhelmingly choosing to have their baby resuscitated. I agreed with that policy but can’t help but doubt myself, especially when I read papers like the 2008 paper I previously mentioned.

As that paper showed, people are more willing to let premature infants die without resuscitation than they are other patients. Why this is so has been the subject of some discussion, but it might have something to do with the fact that we don’t really know the newly born preterm infant. Maybe we aren’t as attached to that child as we are to the two-month-old or 50-year-old patients in the study. I have also heard it suggested that, evolutionarily, we are perhaps primed to accept the loss of a premature infant, since such infants throughout history, until a relatively short time ago, usually died shortly after delivery.

In the eyes of the law, there is no justification for resuscitating a two-month-old but not resuscitating a newly born, extremely preterm infant. Once born, both are independent beings in the eyes of the law and deserve the same consideration. However, this doesn’t mean that differences in resuscitation practices don’t occur based on age. We often rightly try to keep the law out of end-of-life decisions.

This brings us back to the question of whether it is acceptable to let a premature infant die when they have the same chance of survival and good outcome as an older patient. I don’t believe it is, although I have seen this scenario play out many times. A human is a human, and the fact that they cannot advocate for themselves should not affect our judgment. Should the fact that we don’t really know the preterm infant affect their chances of being resuscitated? Also, historically, many physicians have overestimated the likelihood of impairment in premature infants, and this can color their judgment.

A part of me recognizes that there might be something different about the newly born — though I can’t put my finger on it — but I also know that many advocates for premature infants would argue forcefully that we should not discriminate against them.

And the same goes for the elderly. If a procedure gives them five quality years of life, versus the 20 years it might give a younger person, is that reason enough to advocate for it less? I think it’s hard to say yes to that question.

So, when caring for the very young or very old, ask yourself: “Am I practicing age discrimination? And if I am, is it OK?”

Share your thoughts on the challenges of patient age discrimination in the comment section.

Paul Holtrop is a recently retired neonatologist who lives in northern Michigan. Besides trying to keep up with the medical literature, he enjoys bicycling and cooking, plus watching college football — except, of course, for the cringe-worthy head injuries. Dr. Holtrop is a 2021–2022 Doximity Op-Med Fellow.

Illustration by Diana Connolly