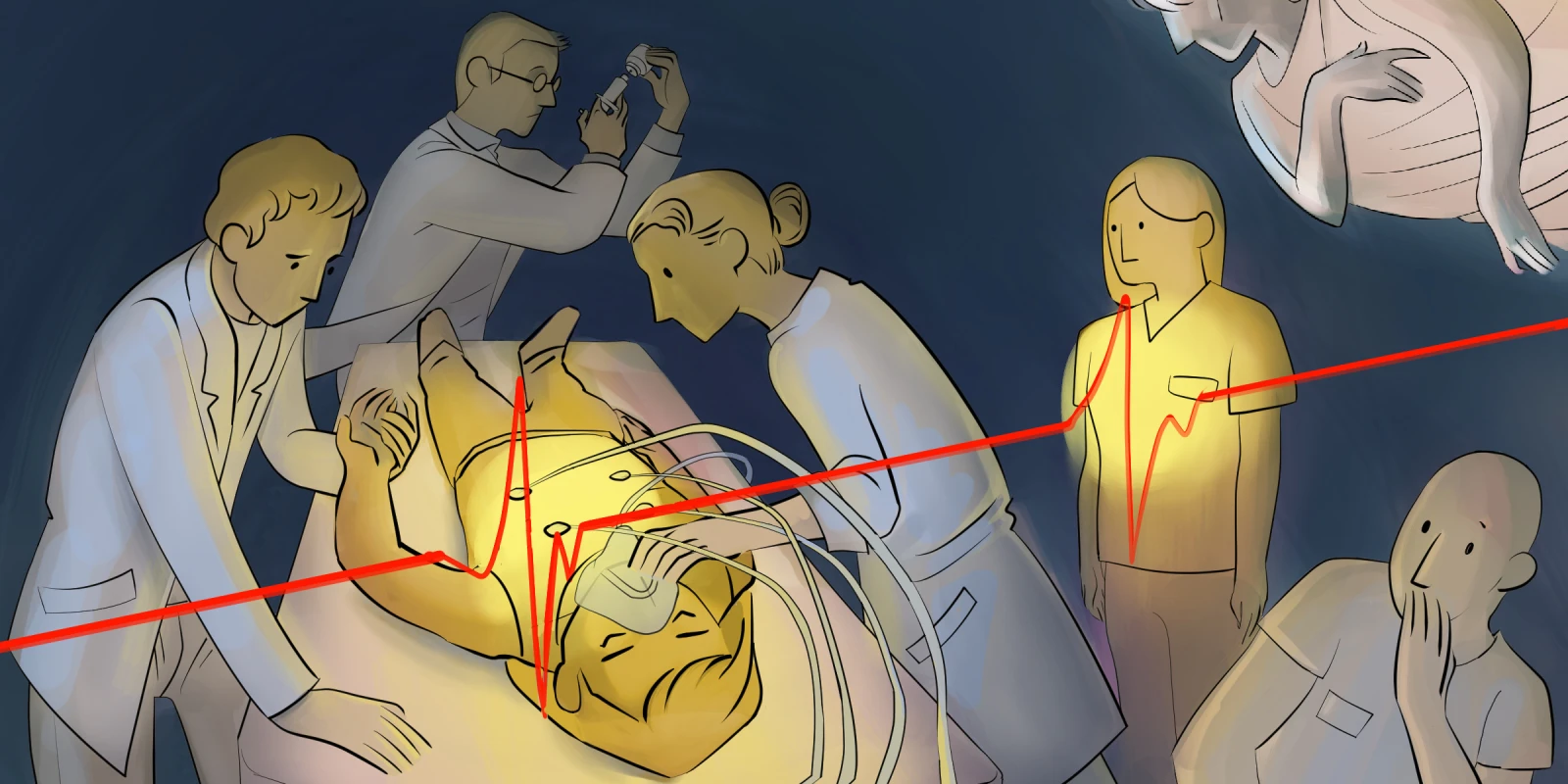

I was trying to keep up during ICU rounds, when all of a sudden, “Code Blue in Room 2 north dialysis” was announced throughout the hospital. The majority of these codes end up being cancelled before we even get a chance to drop everything we’re doing and help. But not this one; this one was very real. For all rapid responses and codes, the ICU physician on the floor is usually the one who goes to see the patient, and we were the lucky medical students who had the opportunity to go with him. As we walked very quickly to the room with the Code Blue, all I could think about was how it was going to get cancelled like always, but that at least I got some steps in. When we got to the patient’s room, however, it was one of the most chaotic responses I’d ever seen during my time on clinical rotations.

In the bed lay a woman, unconscious, being thrown up and down, as people gave her compressions to try and revive her. As much as I was ready to just hop in and do compressions, as a medical student, I definitely felt I was just in the way, especially when someone’s life literally would be in my hands. So I stood at a reasonable distance, still ready to assist when needed. Dr. J, the ICU physician, started to direct the nurses to give him “Epi STAT” and to “hook up the AED.” But as all of this was happening, blood started to form a puddle on the floor underneath the patient’s bed. Everyone started to panic because she was starting to lose liters of blood and her pulse couldn’t be detected. The bed was stuck, which did not make it any easier to control the bleeding. Nurses, technicians, and even Dr. Naji started to lose hope that we could bring this woman back. After 20 minutes had passed, the number of people in the room started to dwindle, and the pool of blood on the floor only grew bigger. “Time of death: 10:46 a.m.,” Dr. Naji called out. And just like that, I had experienced my first patient death.

When I woke up earlier that morning, the last thing I expected to witness was a woman, who I had just seen having breakfast before her dialysis, pass away before my eyes. I didn’t want to leave my spot in the room. The nurse was trying to get the husband on the phone while others started to clean up. The first thought that passed through my mind was, maybe I should have jumped in and done compressions, or been more proactive. Maybe, just maybe, an extra pair of hands would have gotten a little pulse back or stopped the bleeding. But realistically, I knew my “what ifs” and “maybes” weren’t justified because she had received all the treatment that could have saved her at the time. We returned back to rounds as if nothing had happened, and that bothered me. Later that day, I got home and just cried.

The image of the woman lying down, covered in blood and pulseless, replayed in my head for a couple of weeks. It was difficult to process, knowing I had to go to work the next day and move on. It’s hard to explain what you feel when you experience your first death on rotations, especially in this manner. You see a life suddenly end within a few minutes, even though there is a whole staff of clinicians trying to save it. In the medical profession, the expectation is to remain objective in order to avoid emotions interfering with the treatment of patients. If we aren’t, this can impact treatment plans, which may or may not be in the patients’ best interest. Medical students’ humanistic values are said to decrease drastically as we enter clinical rotations in our third and fourth year. As much as we are taught to always be the most “humanistic” we can be, it’s hard when you don’t have the “perfect” patient — a patient who is completely healthy and compliant with all your counseling and treatments. As a medical student, when you see patients who are either not compliant with treatment or pass away, you are often not given enough time to process it properly because you’re needed to help other patients. There wasn’t a course or lecture that taught me how to cope with death while continuing to treat other patients at my medical school. Although we all handle death and grieve differently, having the skills to process emotionally taxing events during clinical rotations would be beneficial to any medical student.

The experience I had is something that will always stay with me and help shape me into the kind of physician I aspire to be. I want my patients to trust that I will always care about their health and well-being. It has made me stronger and more capable in dealing with a patient’s death, especially when I have absolutely no control over the outcome.

Ariela Alonso is a fourth-year medical student at Nova Southeastern University College of Osteopathic Medicine. She has an interest in gynecology, oncology, and reproductive rights, and is applying for ob/gyn residency this cycle.

Illustration by April Brust