In summer 2024, Doximity ran our Women in Medicine essay contest. We are happy to announce this as the winning essay.

I basically just started, and I’ve already failed at the U.S. health care system.

One year ago, these were the words that filled my brain every hour of every day as I realized that I wasn’t cut out for my job. My dream job. The one I had felt was my calling.

When I moved to a town in rural Arizona, I knew I was joining an incredible team of physicians. There aren’t many places left in the U.S. where family physicians practice with the scope available there. I signed up to use the full breadth of my residency training, caring for adults and children in outpatient and inpatient settings, even including surgical obstetrics. My coworkers were collegial and personable, and we regularly shared our own lives and consulted each other on perplexing patient cases. I never had any doubt that, even in the middle of the night, someone would come assist with a C-section or help resuscitate a baby while waiting for the NICU flight team to land. I loved my coworkers, and I felt that they genuinely loved me.

Yet, the adrenaline wore off after about 18 months, and the intensity of the practice started to sink into my core. I slept poorly on call nights – regardless of whether I went in to deliver a baby – and I felt sluggish with a full clinic load the next day. In the past, I had taken great pride in my ability to empathetically respond to patient concerns, but I struggled to do this in 15-minute visits. Weekends (when not charting) were spent hiking alone, desperately trying to recharge my “social batteries” that my work drained completely. As a very introverted person, I would arrive home after a day of constantly talking and have no remaining energy to connect, even with my partner.

I began a group coaching program, learning tips for clinic flow and how to shift my thoughts about my work. I optimized my EMR use to the point where I left most non-call days 30 minutes after the last patient, with inboxes empty and all notes done. I rejoiced, “This will finally fix my problem!” but soon I found that even though my free time increased, I was still too socially exhausted to create any sense of community outside of the clinic.

I asked for a pay cut so I could reduce the number of patients I was seeing but was told it wouldn’t be financially feasible for the clinic. For the next few months, I dragged myself out of bed, somehow scrounging up enough energy to fulfill my clinical duties but at the expense of my own well-being. Through coaching and therapy, I’d come to embrace my introversion as integral to my personality, even believing it to be a beautiful part of my practice because it allowed me to engage with patients on deep and difficult topics since I wasn’t afraid to “go there.” But the 15-minute visits were soul-sucking, and it had little to do with chartwork. This was unfortunate, because AI, scribes, and fancy technology weren’t going to solve the problem.

“It isn’t different anywhere else,” people told me, and as I browsed job listings, I found they were mostly right. The comment that hurt the most, however, was this: “If you leave, you’re the reason the health care system is collapsing and there aren’t enough doctors.” I spent months processing this statement and releasing the sense of responsibility for these dire circumstances. However, the guilt I felt about leaving ultimately wasn’t enough to overcome the need to save myself.

I basically just started, and I’ve already failed at the U.S. health care system.

Nine months ago, after investing over a decade of my life to get there, I left my incredible job with its incredible people. If experiencing an existential crisis weren’t enough on its own, my partner and I also split, and I made the heartbreaking decision to euthanize my 17-year-old cat. It felt like my life was razed to the ground, and I would have to start over from scratch as a single, childless woman in her mid-30s (a state which many in society would call “failure” all on its own).

Yet, despite all those fears of personal and professional ruin, my life has been anything but a catastrophe. After a contemplative 550-mile walk across Spain on the Camino de Santiago this spring, I began experimenting with removing myself (as much as possible) as a commodity in “The System.” I’m giving away my skills at a free clinic, performing medical evaluations for asylum seekers, and starting work with a local search and rescue organization. I work as locum tenens one week a month to pay the bills, and during my first shift, I wept with gratitude at the realization that I do still love the practice of medicine. This portfolio career may not be what I do forever, but I’m having an incredible time indulging in my curiosity even amid the uncertainty.

Do I think I’m a failure now? Hardly.

It was tough to release the life I’d envisioned as a physician woven into a community, caring for multiple generations in the same family. However, I’ve grown to deeply appreciate this time for what it is: a unique, incredibly precious opportunity to create my life from the ground up, but now with skills and experience and a deeper knowledge of myself. I recognize that this isn’t something that many people get to do, and I intend not to take that for granted.

If you had told me when I was 20 that I’d get to this point and still not know what I’m going to do for “the rest of my life,” I might have told you that sounded terrible and that I wanted my money back.

But if you told me that I’d get here and find my life grounded, playful, and adventurous – even if the path to get there was winding and painful – I’d probably say, “Oh yeah, bring it on.”

Elisa Troyer is a family physician and currently delving into her fascination with the intersection of climate change, migration, and health. In her free time, she is probably outside somewhere, though she might be adding an occasional post to her amateur blog, A Sense of Impending Bloom.

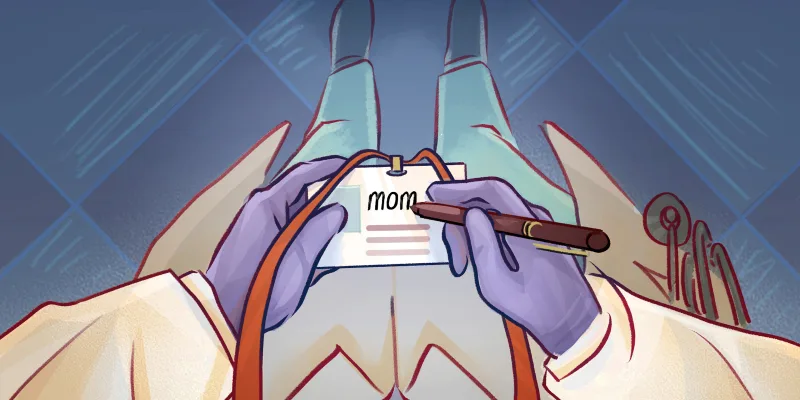

Illustration by April Brust