As a card-carrying member of the Coalition of Type A Persons, I certainly understand the need for certainty and the desire to plan. I am constantly trying to find a more efficient way to organize my day and create space for new organizational structures. In most ways, the act of working in the ED fits this desire and this need very well. Patients are pieces to move through a system and as you figure out the best ways to move them through that system, you gradually become more efficient.

Nothing can happen until plans are made, and things need to happen to move forward. This is a need in healthy times, but also in sickness. Patients who arrive at our door in the ER do so for many reasons, not the least of which is the desire to know “What’s going on, and when will it be over?” The problem in the ER is that we can answer these questions with certainty and precision only when we are also giving bad news. The best answer one can hope for in the ER is, “Not sure what’s going on, but at least it’s not a heart attack!”

Working in the ER is a daily act of hoping to forestall certainty. Certainty, in our world, is only bad news. By definition, the ER is designed to find and care for emergencies. Also by definition, emergencies are not good things to have. No one wakes up on a beautiful spring morning and thinks to themselves, “I’d like to have an emergency today.” More likely you wake up feeling sick and say, “Boy, I hope this is NOT an emergency.”

Our vocabulary for this is “the rule out.” As in, we try to rule out the possibility of a disease. From a purely scientific perspective, this is not possible, but Minister Bayes, the patron saint of evidence-based medicine, can get us close. Patients arrive and seek care for symptoms, which we evaluate using tests and attempt to prove that they do NOT have a subset of serious illness. When we do, we are happy, but our patients are still uncertain. When we fail, we give our patients a definite answer, but that answer is bad.

My, what types of illnesses there actually are out there in the world. Despite the myriad organ and physiologic systems, all human illness can be broken down into two dichotomies, and four categories. Illnesses can be diagnosable or non-diagnosable. Illness can go away, or not go away. A 2x2 table then shows us that you can show up in the ER with four types of illness: diagnosable or not, and it may end, or not. Obviously of the four types of illnesses the two worst options are those that won’t go away, which includes the fact that all illnesses “go away,” when the patient dies. If the illness isn’t going away, it may give some comfort for that illness to be definitively diagnosable, but it’s a small amount of comfort in the face of a lifetime of continued illness. The disconnect between ER doctors and everyone else is that we know that in our line of work, the best option is actually a non-diagnosable illness that will go away.

Think about that statement for a moment. If you have to get sick, you obviously want an illness that will go away, either with time or treatment. Most people show up to the ER hoping for this type of illness. They want their pain or symptoms to go away, and they want to feel better. But they also show up wanting an “answer.” It’s this desire that’s the true disconnect, and the hardest part of managing expectations in the ER. Remember, the ER is for emergencies. The answers we give are emergency answers. No one wants emergencies! If an ER doctor can put a label on what you have, that label is bad news.

But if we can rule out the bad stuff, and make sure it isn’t something that won’t ever go away, that means you can leave! You won’t be given an answer, but you’ll be free of emergencies. This is the contradiction at the heart of emergency medicine. For those of us who chose this field, we all imagined that we were the diagnostic engines of the house of medicine. That isn’t wrong, but what is wrong is that we don’t get to give our patients good diagnoses. We can give them emergency diagnoses, or we can rule them out.

The hardest corner to turn in the career of any ER doctor is to become comfortable with a discharge diagnosis that is simply the chief complaint. Patient arrives with abdominal pain, diagnosis: abdominal pain. This seems unsatisfying because we all want answers. But when the answer is between “ruptured aortic aneurysm” and “I don’t know, but at least it’s not a ruptured aortic aneurysm,” it’s clear what most people would prefer.

What's the last not-bad-news you gave? Share in the comments.

Dr. Ryan Richman is an emergency medicine doc in upstate NY. Father of three, married to a pediatrician, and holder of several patents, he's an amateur baker and semi-professional Star Trek scholar. Also, anything with Matt Berry. If people still tweet (or X-plain?) he's @RWHRichman. Dr. Richman is a 2023–2024 Doximity Op-Med Fellow.

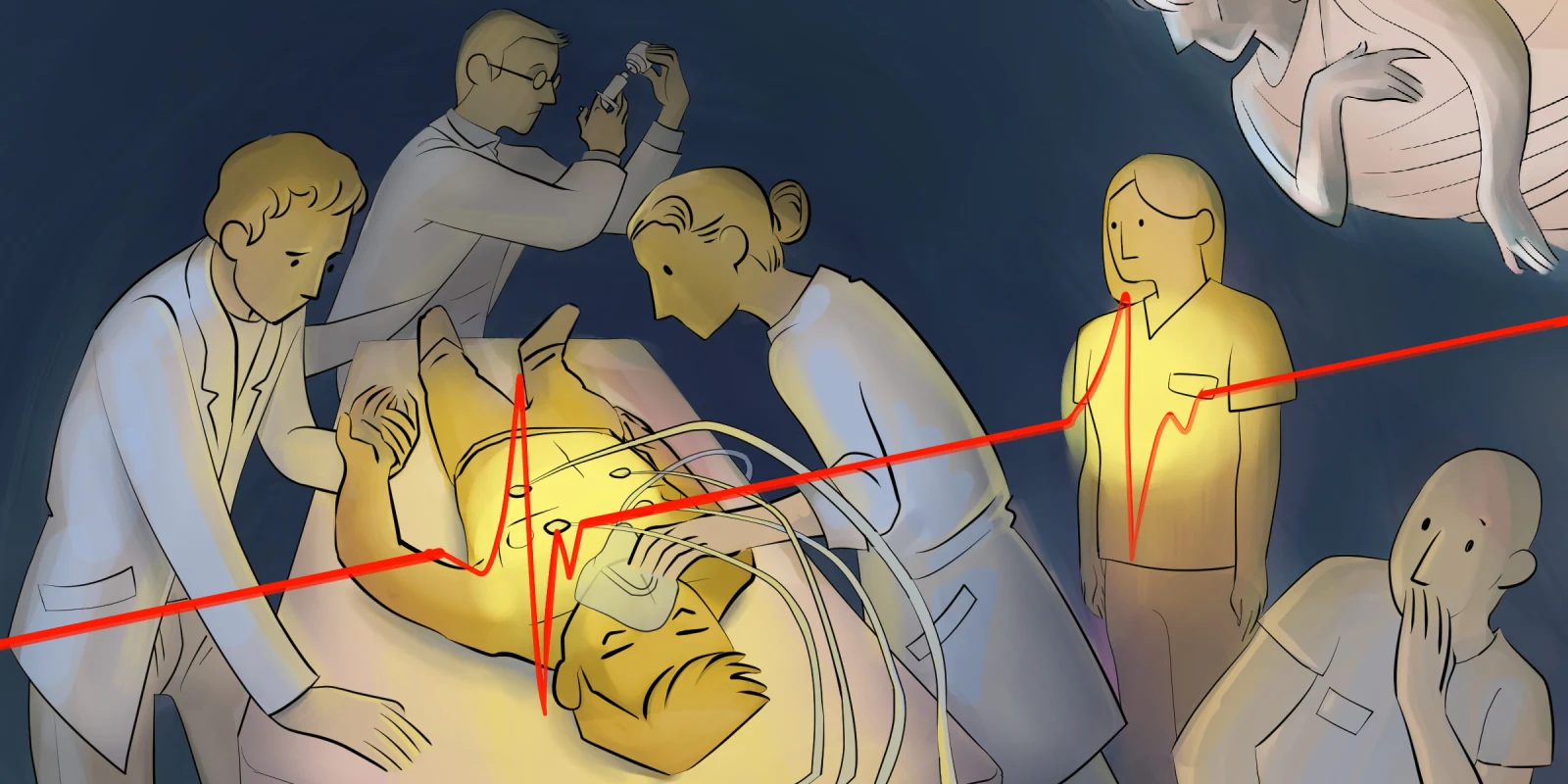

Illustration by April Brust