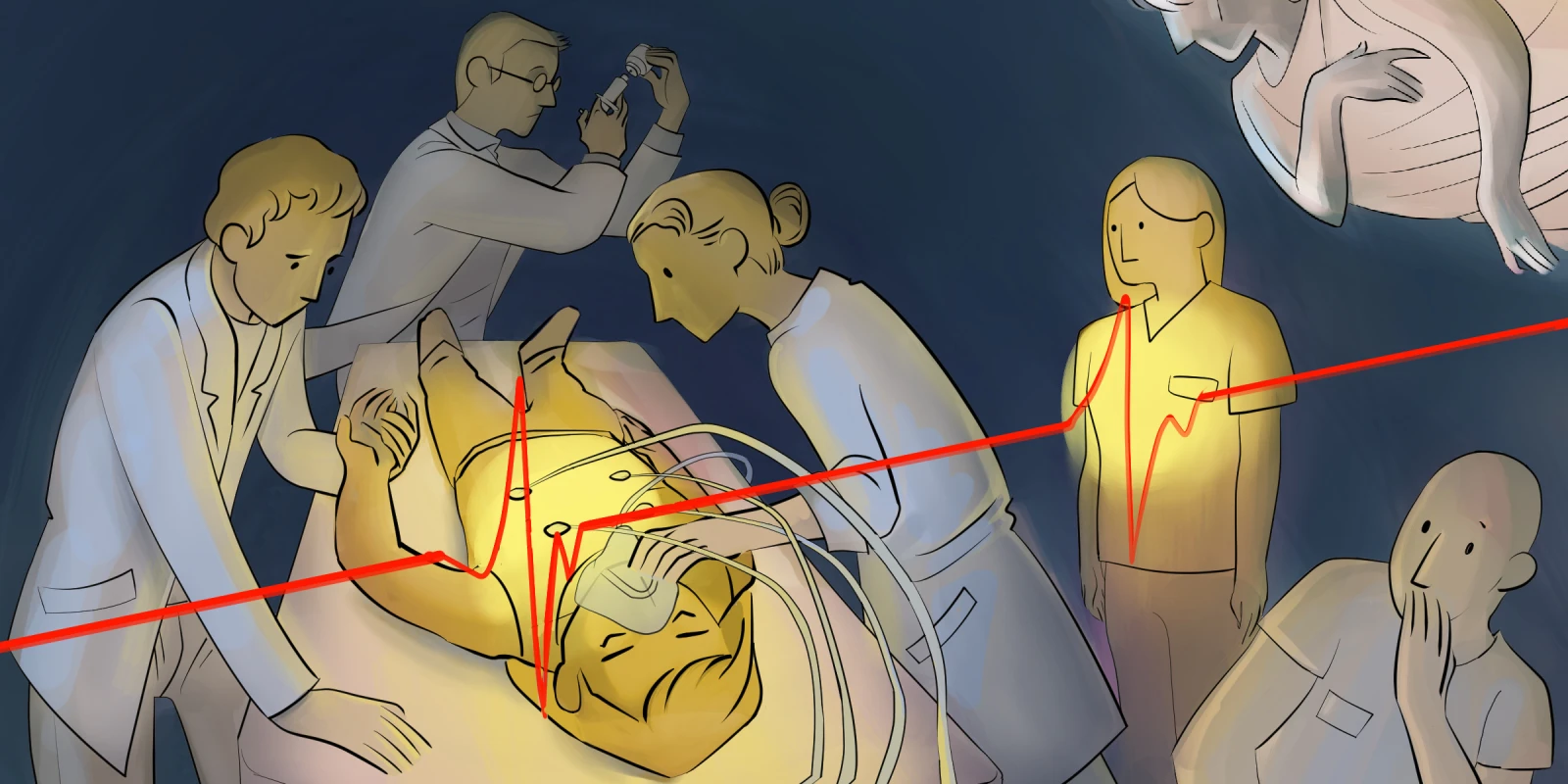

When I first laid eyes on Ms. Johnson she was intubated and sedated in the ICU bed. I was struck by how young she appeared at 60-plus years old, especially after hearing about her history of alcoholism, tobacco use, diabetes, prior cardiac stent placement, and long battle with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). She was on several pressors and was mechanically ventilated with a high positive end-expiratory pressure and supplemental oxygen level at 100%. The sedation made her appear calm, but the hypotension and low oxygen saturation on the monitor showed me she was struggling. The nurse told me Ms. Johnson wasn’t doing well, and probably wouldn’t make it.

Prior to my ICU rotation, I hadn’t encountered many critically ill patients. I was accustomed to the “bread and butter” medicine featured at the Veterans Affairs (VA) hospital where I had completed my internal medicine rotation nearly two years ago — the occasional CHF or COPD exacerbation, an AKI or two, an elderly gentleman with a fall. One VA patient, diagnosed with metastatic liver cancer, died several days after I admitted him. When my attending told me, I cried in front of her. It was the only time I had dealt with death as a medical student. As my first ICU patient, Ms. Johnson was the “sickest” patient I had cared for. Her problem list was long: acute hypoxic respiratory failure secondary to severe sepsis, septic shock versus cardiogenic shock, likely pneumonia, AKI, diabetes, chronic iron deficiency anemia, chronic thrombocytopenia, depression. I hoped she would make it through the night.

The next morning, at sign-out, my attendings talked about two patients that had died the night before. Neither were Ms. Johnson. I felt simultaneously saddened to hear about the two patients and relieved that Ms. Johnson had lasted the night. I wondered how my attendings dealt so well with the news of their patients. I wondered if I would be able to handle my patient’s death the same way. I wondered what Ms. Johnson’s voice sounded like.

Several days passed, and Ms. Johnson carried on. Her echocardiogram revealed a normal heart. She received two units of blood for a hemoglobin below 7 grams per deciliter, and became intermittently hypotensive. After about a week, she no longer needed pressors and her ventilator settings were minimal. We gave her diuretics to remove the 6 liters of fluid she had retained since admission. She failed her first spontaneous breathing trial after 20 minutes, but the respiratory therapist was hopeful. The nurse told me Ms. Johnson was doing well.

After nearly two weeks, I walked in the room and was surprised to see Ms. Johnson sitting up in her bed. She waved at me. She was still under the effects of sedation but was able to follow commands. My attending told me she would likely be extubated today. A few days prior, I had facilitated the transition of another patient of mine to comfort care. His family was with him that day, and I left Ms. Johnson’s room to visit them. When I arrived, they were crying. The patient was frail but appeared comfortable. I sensed he would not likely last the night.

Later that day, I returned to Ms. Johnson’s room. She was extubated, and we were working on transferring her to the hospital medicine service. I introduced myself as I did for several weeks. She looked up at me with acknowledgment. After listening to her heart and lungs, I told her she was doing better and would be leaving the unit that day. I wished her well. She smiled at me. While walking toward the exit, I heard a soft whisper from across the room and barely made out the words: “Thank you.” I turned around expecting to see the nurse, but only Ms. Johnson remained behind me. It was the first time I heard her voice.

Do you recall your first time providing care for a critically ill patient? Share your experience in the comment section.

Rob Shaver is currently a fourth-year medical student at the University of Minnesota-Twin Cities.

All names and identifying information have been modified to protect patient privacy.

Illustration by April Brust