Last year, during my first year of online medical school, I participated in a school-wide learning series called “Colloquium.” A program spanning 10 hours across the whole year, Colloquium provides information about various topics in the field of medicine. Amidst a range of subjects from retrospective research studies to the human microbiome, there was one in particular that stood out to me — “Artificial Intelligence in Health Care.” For me, artificial intelligence (AI) called to mind Siri and Google Assistant, which seemed to work through a magical string of codes. Having already been forced into the digital world of Microsoft Teams and 3D Anatomy Atlases due to COVID-19, I suspected that AI was growing closer to reality than ever before. So, I signed up for the course.

As my classmates and I listened to the various discussions on the changing face of technology and medicine, I noticed that AI brings forth thousands of questions, most notably the question of what it means to be human. When a person starts an argument, we can attribute it to familiar emotions of rage and frustration, and are able to relate to what that person must be feeling in that moment. When something deemed a machine starts an argument, we are suddenly faced with the question of how we can tell if it — or any individual — has empathy for others, how one determines the difference between good or bad.

In the media, AI acts as a mirror of our own fears: In “2001: A Space Odyssey,” the computer system takes over the entire spaceship, turning rapidly from a system designed to protect its crew into a malevolent force. The movie iteration of Isaac Asimov’s “I, Robot” likewise shows that no matter the original intentions of AI, its very existence can still rapidly subvert itself and turn evil. Or if not evil, then certainly morally gray.

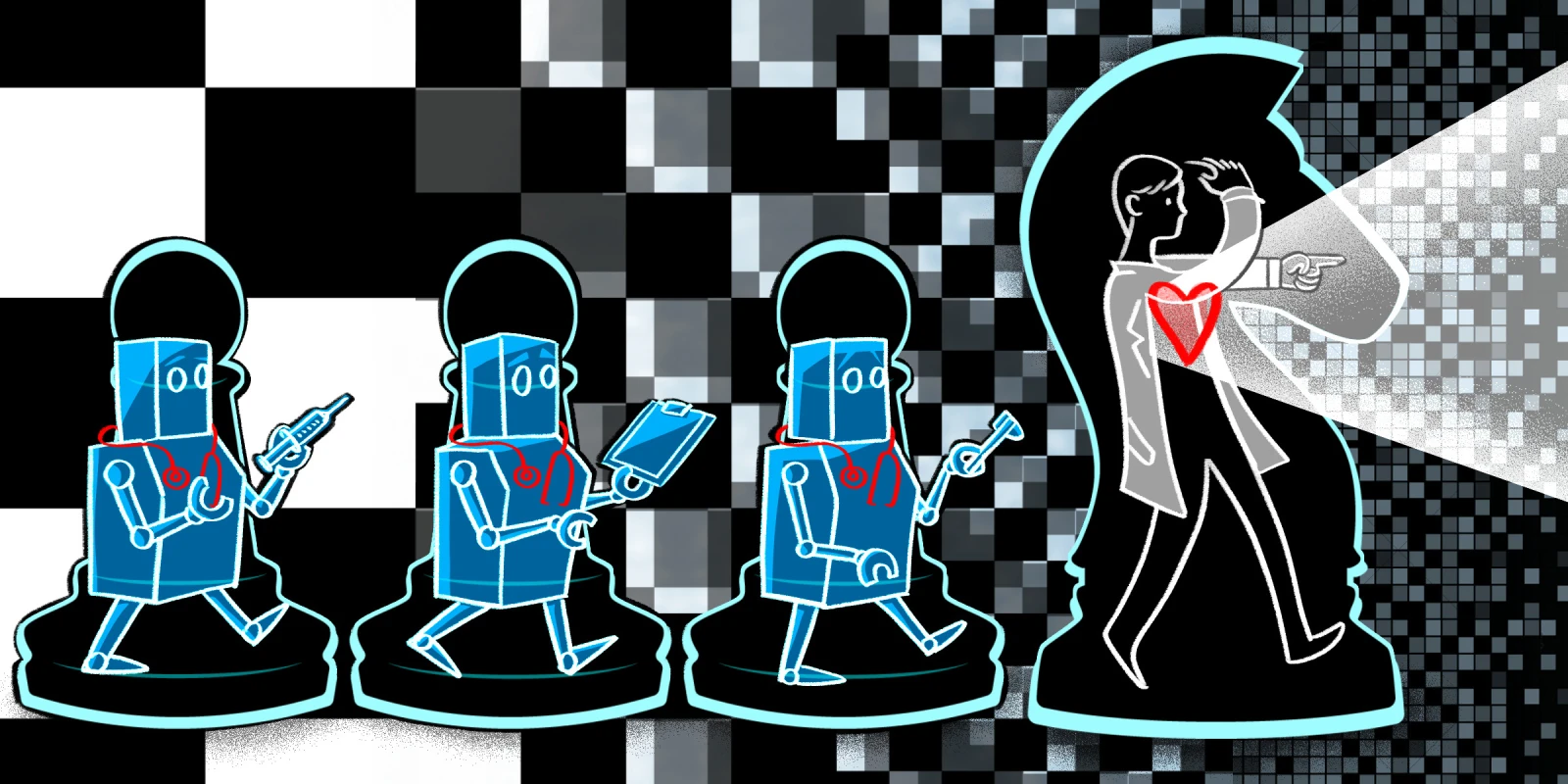

The funny thing about media is that the same way it portrays AI, it also portrays clinicians. Clinicians are supposed to be forces of good, with their programming (i.e., medical school and residency) designed as a set of codes for delivering ethical and compassionate care. In the same way that the robots of “I, Robot” are encoded with the law “A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm,” clinicians are commanded to follow the Hippocratic oath “Do no harm.” And yet, famous fictional clinicians like Dr. Jekyll/Mr. Hyde and Dr. Frankenstein are often depicted as heroes who set out with an aim of creating cures or preventing death and then inevitably turn into villains who subvert their own moral codes.

Perhaps these similarly sinister portrayals are the reason the medical system is faced with the dilemma of patients who need care, yet are afraid of seeking that care. Across both AI and medicine, there’s a veritable fear of the unknown and the complex. From the new ability of social media to advocate against clinicians’ invalidation of patient concerns to the lawsuits against those same social media platforms for privacy violations, both medicine and AI are often (perhaps too often) defined by the morally gray.

So, why does the U.S. health care system aim to incorporate AI into medicine if both entities are treated as corruptible by our media and news publications? The same reason we make the daily effort to expel the mythologies around the practice of medicine and to provide compassionate care. Medicine is not formulaic or predictable, and can’t be defined by a few lines of codes or equations — yet it is still worth practicing. We are not all the Dr. Jekyll who becomes the evil Mr. Hyde, the Dr. Frankenstein who builds a monster, or any other caricature of our practice. One bad apple doesn't spoil the whole bunch — we clinicians are able to constantly improve and fight against the pitfalls that may appear within our field.

Likewise, the advent of AI has the opportunity to bring changes to medicine that we can only dream about. Much more expansive than a little assistant in your phone, AI encompasses programs designed to facilitate diagnoses and treatment plans that are centered on the patient. As just one example, its efficacy for detecting cancer has been extensively documented.

In addition, AI can bring medical access to rural communities — which is a step forward in combating the socioeconomic disparities that compromise quality medical care. Furthermore, AI may be capable of improving our communication with patients in a way the EHR never could: In the near future, AI could well become a virtual listening assistant, filling out charts while we speak with our patients and providing personalized, evidence-based suggestions for treatment.

Yet in order to offer these options to ourselves and our patients, we have to look in the mirror and conquer both our own fear of AI and society’s fear of the “horror movie doctor.” Because truthfully, we love our patients. We are unlikely to turn into that horror movie doctor anytime soon, as we entered this profession out of a sense of compassion. However, issues that plague clinicians like overwork and burnout can make it hard to constantly return to that place of compassion — which is why it could be good to take some of the load off via AI.

So, when you see new AI technologies knocking on your practice door, don’t forget that at one point things like online medical school were never the norm for medicine — and that you once stood like me at the beginning of your career, filled with uncertainty about what it means to be a good doctor.

What are your views on AI in medicine? Do you implement it into your own practice, or are you apprehensive? Share your thoughts in the comments below.

Ashley Mason is a second-year medical student at the University of South Florida in Tampa, Florida. She began her M.D. journey during 2020, and has a special interest in how improvements in medical curricula and the field of medical education can in turn change the face of medicine.

Illustration by April Brust