STMM (short-term medical mission) trips continually attract clinicians and other medical health providers as a way to reach underserved communities. According to research, the U.S. leads in sending clinicians on STMMs with a cost of at least $3.7 billion to fund these STMMs — doing anything from nursing education to gastroenterology care. Doximity’s Dox Foundation is one of many that helps provide funding for clinicians to participate in STMMs.

A common criticism of STMMs is that they do more harm than good. One issue is with the limited follow-through the local community is able to provide once clinicians leave. How helpful are STMMs in the long run? How can long-term sustainability be achieved once clinicians leave?

Where Does One Start?

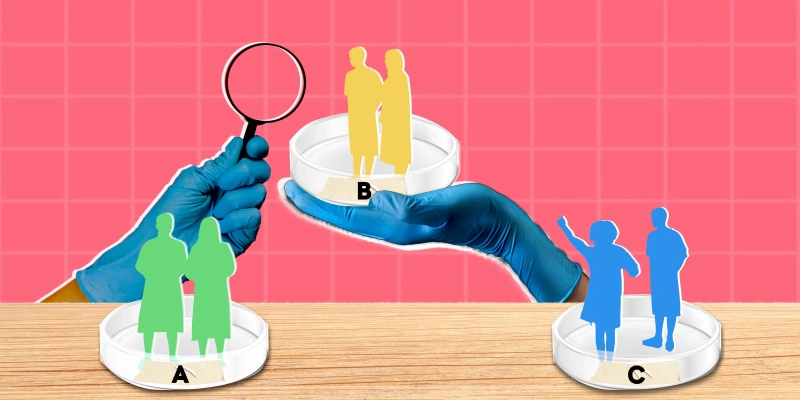

It may be helpful to decide whether you want to go on a STMM on your own or if you want to join an already established organization. Both Adele Dobkowski, NGO sustainability consultant with CESO (Canadian Executive Service Organization), and Dr. Crystal Wiggins, audiologist with Faith in Practice, recommend thinking about the following questions to help start the process. These questions can be applied to both individual STMMs or joining an STMM team.

- For how long am I looking to serve?

- What service am I looking to provide and where can I fit in?

- Are there other outside organizations in the same area providing similar services that I can reach out to and collaborate with?

- What local person, team, or community can I partner with?

Once these questions are answered, more specific questions and research can be done related to your specific project.

How Do I Do My Best While I’m There?

Serving in an STMM can go by very quickly with not a lot of time to process your actions and emotions. Dr. Wiggins recommends carving out time each day to keep a very detailed daily diary. She suggests documenting the following:

- The number of patients seen that day (you could be seeing 30 or more)

- The needs presented and treatments provided

- The challenges in diagnosing and treating, and how those challenges were resolved

- The condition of the facilities and equipment used

- The adaptations you needed to make because of situations, patients, and environment

- What you learned culturally and socially

- Personal hardships

Often, teams that follow your STMM will want to know some of that information so they can provide the most effective and efficient care in a limited amount of time. Once back in the comfort of your typical environment, decompression and natural forgetfulness set in, and you will be glad for having kept such comprehensive daily notes.

Other recommendations to consider while serving:

- Be flexible and creative. The plans created before entering the host country may change based upon the local resources. Dr. Wiggins reminisces about having to use books to prop up a wall otoscope because that otoscope was unable to be hung on a stone wall.

- Stay organized with alternate plans. It can be a challenge to work efficiently and effectively while not having what you are used to having in your own environment — such as more consistent electricity.

- Train locals and gain buy-in. Dobkowski emphasizes the importance of buy-in and training locals for sustainability. To gain that buy-in, it is really important to understand, respect, and listen to the people’s needs before fixing the problem – not going in with just your own specific purpose.

How Do I Keep The Improvements Going Even When I’m Gone?

One of the greatest benefits of an STMM is the immediate positive impact clinicians have on a community that can be easily recognized by all. The question becomes, “after these patients receive the surgery or medical procedure, what happens to them in follow-up?” Both Dobkowski and Dr. Wiggins expressed the importance of developing a strategic plan for sustainability by training local staff, and if possible, help in developing planning processes for the local community to follow through with patient care.

The most important thing a clinician on an STMM can realize is that the follow through is not done by them or another team, but by those who live there.

For sustainability to be achieved, buy-in from the local community is essential. One way Dobkowski gained buy-in for a project in Guyana was by having a stakeholders consultation prior to entering the country in order to truly understand what was needed by the local community. From there, the team gained a general idea of the capacity in which the host country could actually move with the need. This led to a better understanding of how the STMM can be most effectively used by the local community.

Dr. Wiggins took the time to train local people who had learned and developed some knowledge in Audiology to primarily provide interpreting services between STMM practitioners and patients. In addition, these trained locals provided basic audiology services when there was a gap between STMM teams coming into the country.

Dobkowski expresses two main fears in providing services in developing countries: confusing the locals by providing different information (or the same information in a different way), and providing information not appropriate for the targeted audience. To help reduce those concerns, Dobkowski’s approach to sustaining a project in Tanzania was to collaborate with other CESO volunteers who were also tasked in providing similar services in Tanzania. This was done through organizing a Dropbox for these CESO volunteers to share their work plans, information, and training materials used to make sure communication was uniform.

Consistent and reliable communication with the local community after you have left is a huge part of sustainability. More than likely, locals will have further questions and need clarifications after you leave. Often times, the local community may not want to tell you they need that support for fear of judgment, so they stay quiet and you assume all is well. It is important to ask them to tell you what they are doing instead of asking them if they have questions or if they understand. Having them explain their actions will help you help them more productively, and will allow them to give better help once you have gone.