Social connection is an innately human and necessary need, perhaps just below water, food, and shelter. Connections we make with others are a foundational building block of not just our own personal lives, but the fabric of society itself. The neighbors who help babysit a child while the parents head out on a date, the friends who go to a movie together, or retirees playing a card game in a nursing home — these processes are vital components of society, the importance of which is often overlooked.

Social connection is an innately human and necessary need, perhaps just below water, food, and shelter. Connections we make with others are a foundational building block of not just our own personal lives, but the fabric of society itself. The neighbors who help babysit a child while the parents head out on a date, the friends who go to a movie together, or retirees playing a card game in a nursing home — these processes are vital components of society, the importance of which is often overlooked.

As a fourth-year graduating medical student, I have worked in nursing homes whose residents desperately wanted that small human connection, or touch. You could see it in their kind eyes when you went into their rooms to visit, how they would touch your wrist, and perhaps remark with a smile, “You look just like my grandson. Hello!” I cherished these interactions. Sometimes, especially with folks in the hospital, I would have to wake up similar patients with an illness early in the morning, about 5 a.m. to 6 a.m., in order to do my rounds. Most times, they were the opposite of bothered — they would often smile and sometimes even state, “Hey, doc, good morning!” knowing full well I was only a doctor-in-training. I also knew that these patients and residents often had few to no visitors. I would exchange pleasantries and small talk while examining them, if only for a few minutes before I, by the necessity of time, had to move on to the next patient on my list. I know my grandmother, before she passed away, cherished the times the grandkids would visit her in her assisted-living apartment; she lived alone after the passing of my grandfather years before.

The past few years, there has been burgeoning research into the steady increase in the proportion of people who, on surveys, admit to loneliness and lack of social connection in the United States (among other countries, of which Japan is another famous example). Loneliness affects 25% to 60% of older Americans. Loneliness as a risk factor has been shown to be equivalent to smoking 15 cigarettes a day shortening lifespan by eight years.

Additionally, studies have shown that isolation, which can be objectively measured by determining the size of one’s social network, is associated with cognitive decline and other poor health outcomes. This research shows living alone is more common than ever in the U.S.; over a quarter of the total population lives alone, a 10% increase in the last decade. Along with this, 43% of Americans feel that, sometimes or always, their social relationships with others are not meaningful. Interestingly, one study showed that social media usage had an association with the prevalence of loneliness; 73% of very heavy social media users considered themselves lonely versus only 52% of light users.

Public health officials and researchers are alarmed that these figures are worsening; we will have a public health crisis on our hands if nothing is done. Human connection is a vital part of life, and the growing prevalence of single-occupant households and a growing proportion of people complaining of loneliness is not a good sign. We need to invest in more research into this problem, as most research is recent and much is to be learned. We also need to focus on forging and strengthening social connections — be it in community programs/centers for retirees, or after-school activities for youth. Most of all, we must not ignore or downplay this problem; even if you cannot run a lab or perform a scan for loneliness on your patient, the scourge of this affliction is as real and devastating as many other bodily diseases, and it will shorten quality and quantity of life just as much. With a new focus on this problem, there is room for optimism, but there is also much work still to be done.

As a psychiatry intern starting work this summer, I am also very concerned about those intimately affected by the coronavirus pandemic, which will take away many thousands of lives, sicken others, and traumatize many more millions. I anticipate a time in my training when I will have to deliver psychotherapy to those who have lost loved ones in this pandemic, or those who were intimately impacted by it. In a more immediate way, even currently, I see the stress that the pandemic is causing — the frantic rushes for supplies at the grocery store, the concern as to whether family members living in other states and cities are safe. But I also sense that those that were lonely feel that way even more intensely now, cut off from friends, a workplace, or even close relatives. Perhaps they have been furloughed or laid off from a job they were using to support their family. Anxiety and fear are peaking, much of the country is in quarantine, and the pandemic has no end in sight. The reality is, intended or not, that the next few months will be a social experiment in discovering the mental toll this isolation and stress will have on the psyche of this nation.

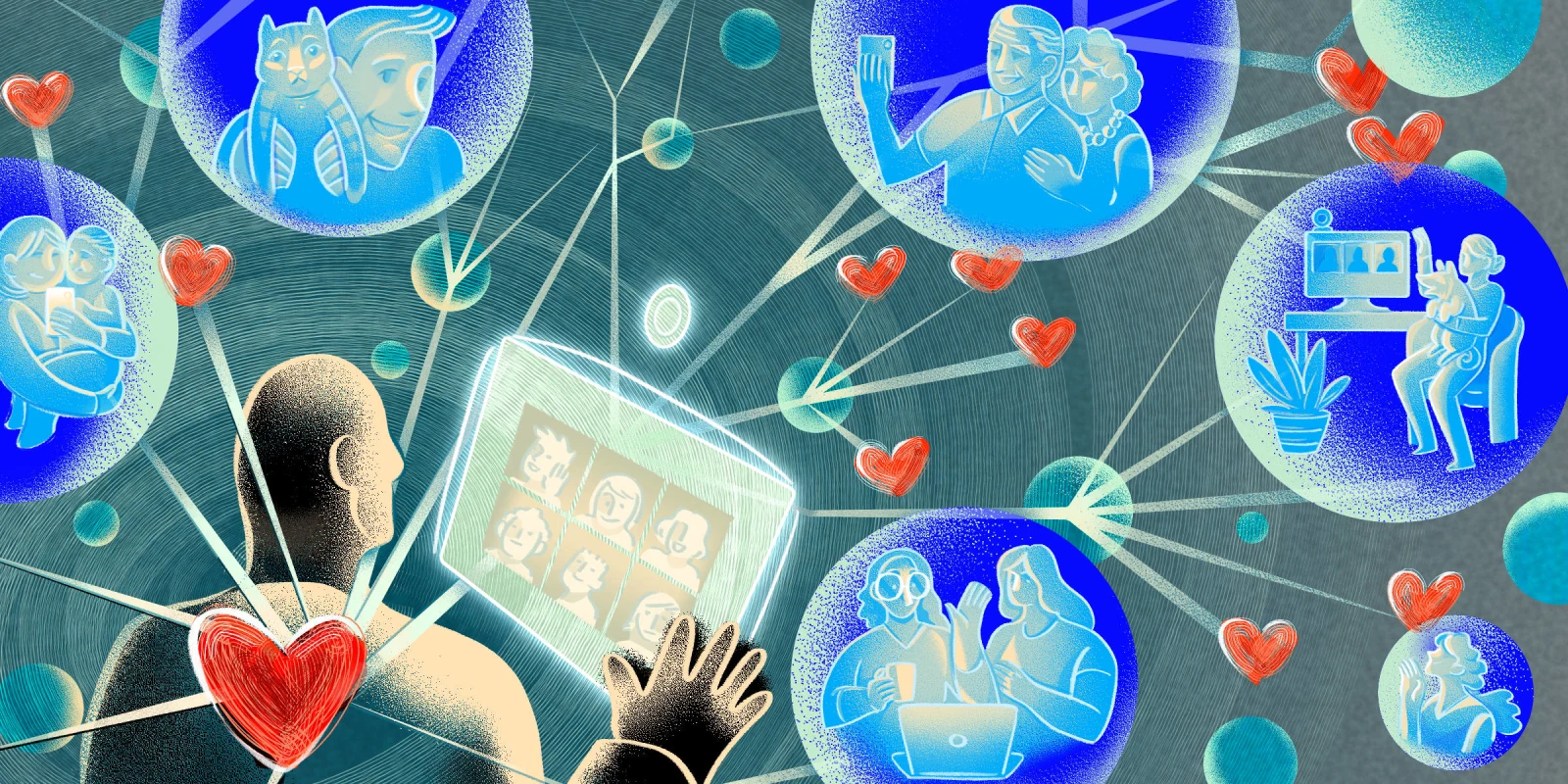

I hope in these hard times we can continue to connect with one another; if not in person, online on social media, through video chats, and through phone calls. Check up on old friends you have not talked to in months, even years. Ask how they are doing, how they are getting through the day. And in a few months, when the dust hopefully settles, we can start to rebuild the social part of society piece by piece. Until then, Zoom, Skype, Hangout, Houseparty to your heart’s content; your friends, family, and co-workers are waiting for the call. I’m sure, like the gracious patients I have met in the hospital, they will be more than overjoyed to see your face or hear your voice. It may be the only face they see that day.

John Lacci is a fourth-year medical student graduating from the University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio. He will start as a psychiatry intern at the University of Chicago this summer.

Illustration by April Brust

Click here to see more perspectives on COVID-19 from the Doximity network.

Click here for up-to-date news about COVID-19 on Doximity.