During a recent protest in Rhode Island, a young man was hit in the face by a rubber bullet, resulting in severe injury to the face and eye. Physicians at Rhode Island Hospital examined the patient’s emergency CT scans and recognized a need for a more nuanced and comprehensive visualization of the complex anatomy.

During a recent protest in Rhode Island, a young man was hit in the face by a rubber bullet, resulting in severe injury to the face and eye. Physicians at Rhode Island Hospital examined the patient’s emergency CT scans and recognized a need for a more nuanced and comprehensive visualization of the complex anatomy.

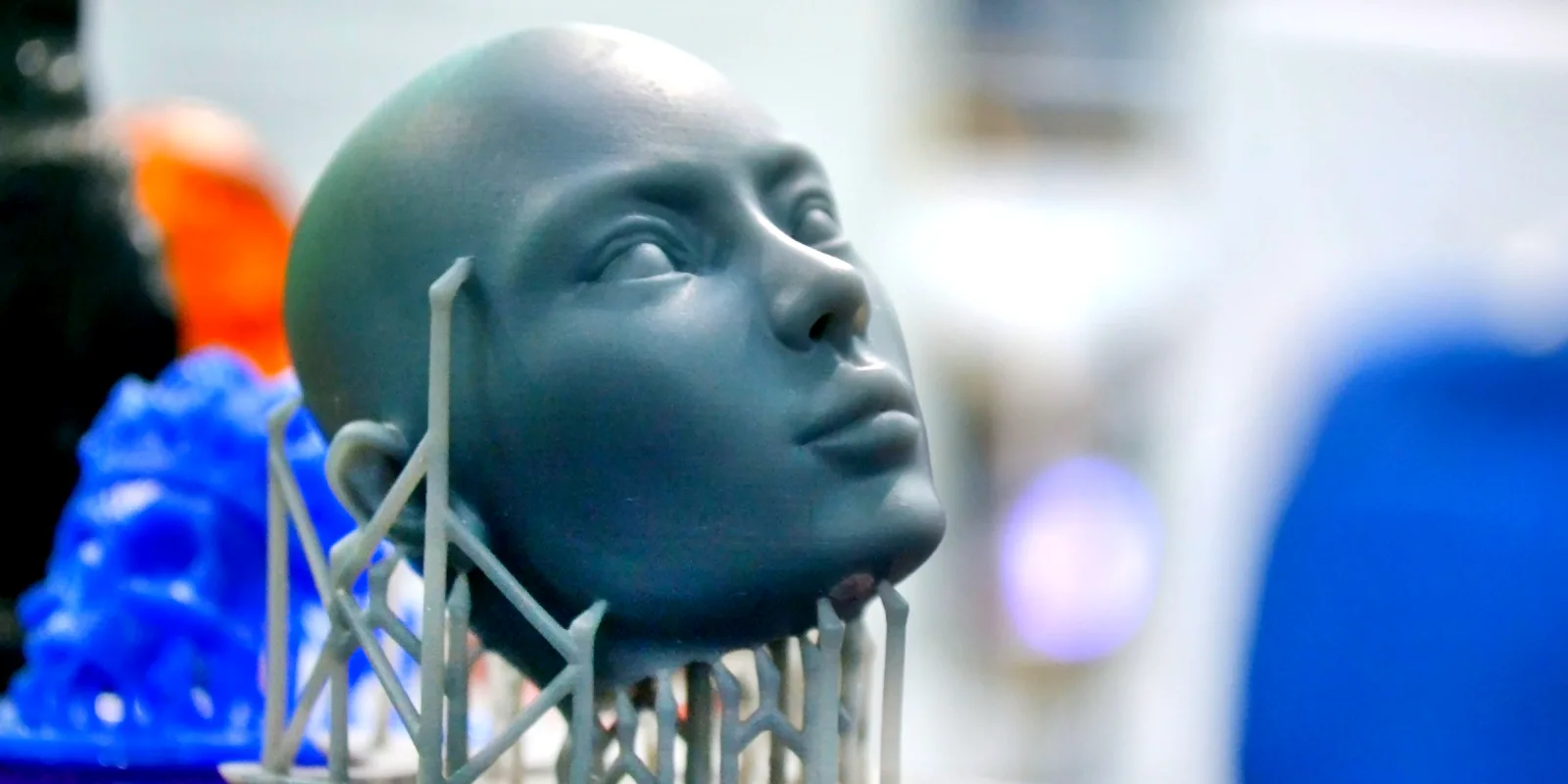

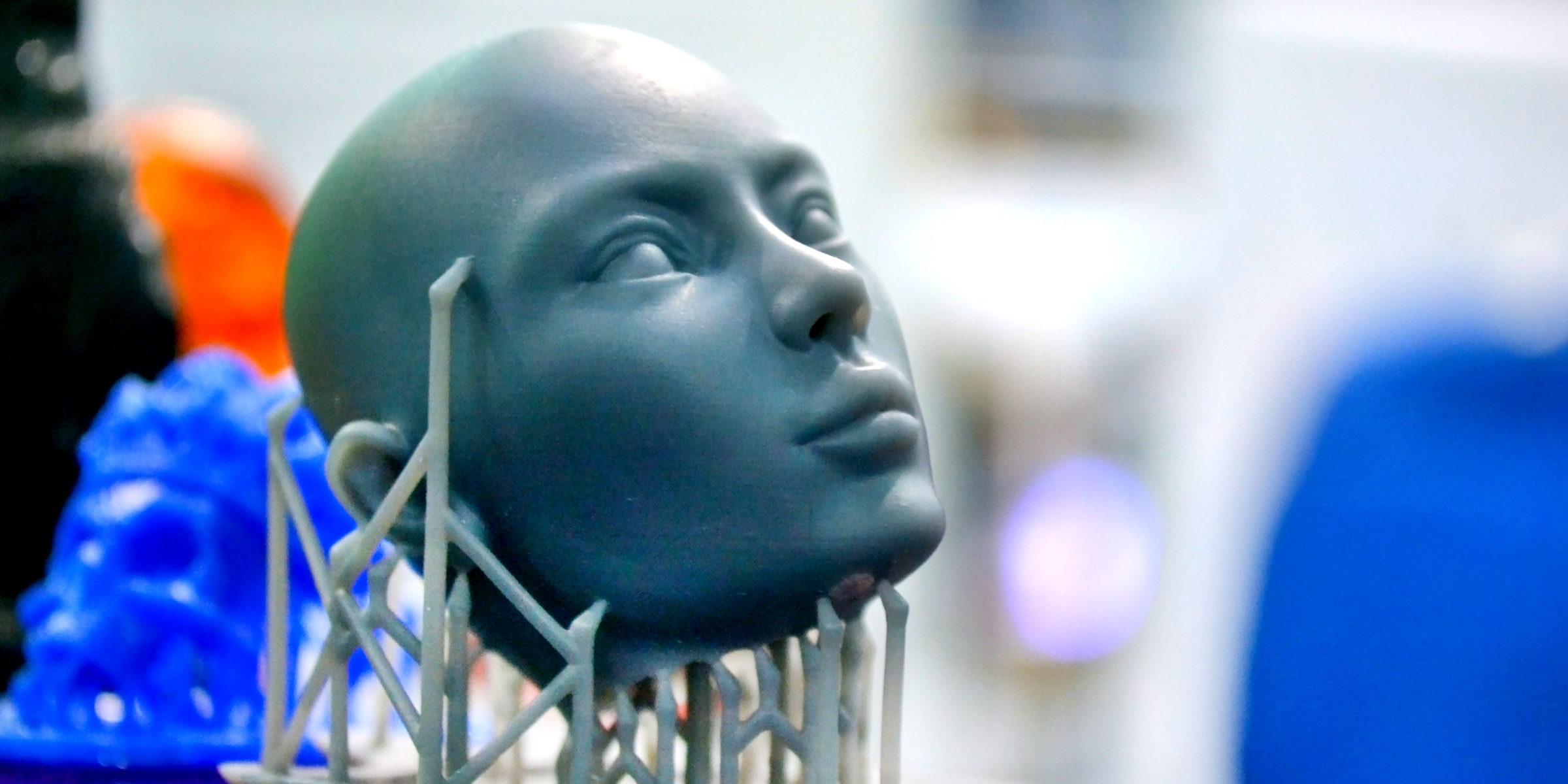

“That’s where 3D printing came in,” said Albert Woo, MD, at the health care 3D printing conference 3DHeals 2020. Dr. Woo heads the craniofacial surgery program at the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University and is director of its 3D Printing Lab.

The patient’s physicians sent the CT scans to Dr. Woo’s 3D Printing Lab, where his team used the imaging data to generate a virtual 3D model. Then they processed and formatted the file and input it into a 3D printer (Stratasys J750) to produce a multicolor 3D-printed model of the patient’s face.

“If there was a simple break in the bone, I wouldn’t have needed 3D printing,” Dr. Woo said. “But in these kinds of highly complex cases where the eye can be damaged and the optic nerve is possibly involved, I can make someone blind if I am off by just a few millimeters. Having a 3D-printed model that shows exactly where the bones are gives me an excellent idea of the 3D anatomy and can serve as a constant source of reference during surgery.”

By examining a 3D replica of the patient’s face, the surgical team was able to appreciate the intricacy of the injury as well as the way it had altered spatial relationships between key anatomical structures. The team used the model not only to plan their surgical approach but also to serve as a reference point while performing the operation.

“We are just starting to tap into the numerous benefits of 3D-printed models,” Dr. Woo told Doximity in a post-conference interview. “They provide an intuitive, true-to-life view of the body, give tactile feedback, and enable you to plan and practice surgeries ahead of time.”

Several groups have identified demonstrable benefits of integrating the technology into medical practice, creating, for example, patient-specific 3D-printed models, cutting guides, and implants to facilitate surgery.

Procedures performed with the aid of a 3D-printed model also have the potential to improve patient outcomes, according to early research in the field. In surveys conducted by Dr. Woo at multiple institutions, physicians reported that 3D-printed models had helped decrease the operating time by roughly one hour for certain procedures.

Despite being used by surgeons and radiologists for years, 3D printing has only very recently begun to secure a foothold in the hospital setting.

“Whereas most people are familiar with the concept of 3D printing, those of us in medicine really have little experience with it overall,” Dr. Woo said. “Many clinicians still view 3D printing as a kind of magic dust that, when applied, allows people to create something ostensibly out of nothing.”

Beyond its surgical applications, 3D printing has emerged as a pivotal tool in the fight against COVID-19. Clinicians’ growing exposure to 3D printing may help pave the way for more widespread integration of the technology in health care.

“I think clinicians realize 3D printing is out there, but they don’t realize fully what the technology entails and what its limitations are,” Dr. Woo said. “There's still a lot of misinformation and lack of information, and that's where more exposure will help demystify the technology.”

To that end, Dr. Woo offered advice on how clinicians interested in using 3D printing at their medical practice can get started.

“First, consider a few ways in which 3D imaging and modeling might be able to help you in your clinical practice," he said. "Afterwards, make sure that you are willing to act on it. The next thing is to ask around. In many ways, clinicians are very insulated in individual silos. We need to break out of these to expand our horizons."

"If you don't have ready access to imaging or a 3D printer, one easy place to start is to contact a radiologist or technician and ask for a virtual 3D model to be created," he continued. "If they have a 3D printer, then it’s potentially easy to translate this into a printed model. If not, talk to local individuals about getting a model printed. Even most public libraries and high schools now have 3D printers.”

Currently, medical 3D printing is predominantly “a labor of love” with the purpose of improving the quality of medicine, according to Dr. Woo. There are, however, various mechanisms by which hospitals have been able to get the cost of 3D models covered.

What’s more, the AMA on July 1, 2019 approved four category III CPT codes for individually tailored 3D-printed anatomical models and surgical tools — a move indicating that medical 3D printing is likely headed toward standardized reimbursement within the next few years.

“I strongly believe that 3D printing is extremely beneficial for clinicians, and it's one of those things where the more you do, the more interested in it you become, and the more you can expand your own capabilities,” he said. “I’m convinced that it's going to be a critical part of physicians’ workflows in the future, and I look forward to seeing how different specialties adopt this technology to improve patient care.”

Have you worked with 3D printing at your hospital or clinic? Share your experiences below!

Image by MarinaGrigorivna / Shutterstock