On my walk one Saturday morning, a neighbor waved hello. Soon I encountered another neighbor, walking her dog, who inquired, “What did that person say to you?” Clearly, she was referring to my neighbor — who is dark-skinned and was clad in black sweatpants and a black windbreaker. I informed her that he is our neighbor, to which she replied, “Ohhhh, I didn’t know! I saw him walking from house to house and didn’t know what he wanted.” My heart sank. My dear neighbor has lived here for over 15 years.

Recent headlines, all horrific, flashed through my head:

A Homeowner in Kansas City, Mo. Shot a 16-Year-Old Who Rang the Wrong Doorbell

A 20-Year-Old Woman in Upstate New York Was Fatally Shot After She and Her Friends Turned Into the Wrong Driveway

2 Cheerleaders in Texas Were Shot After One Got Into the Wrong Car in a Dark Parking Lot

In November 2022 a Neighbor Called Police on a Little Black Girl While She Sprayed Lanternflies

How fortunate for my neighbor that the woman in my neighborhood neither called the police out of fear and suspicion nor carried a gun. And yet, it could have been otherwise.

I am a family physician who has spent my entire career working with people of color and LGBTQIA+ communities. These groups must cope with toxic stress caused by living in a race, gender, and sexuality conscious society that often does not want them to exist. They experience constant implicit or explicit social, political, and economic marginalization. They must be constantly on alert for danger, even during ordinary moments — like standing outside their home, making an honest mistake with directions, daring to live openly, and attempting to thrive.

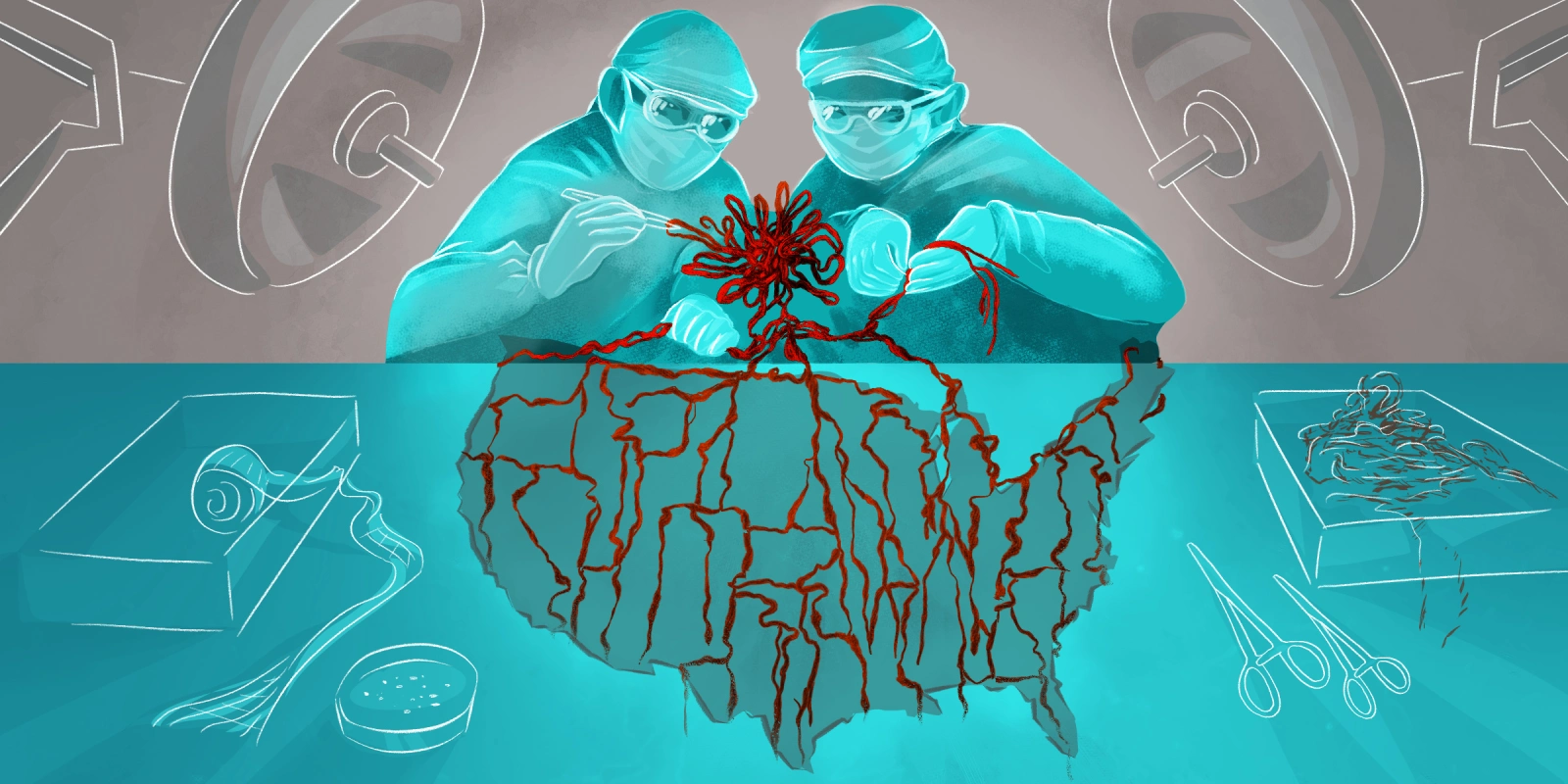

In my 20-plus-year career, I have seen the impact of this toxic stress on the mental, physical, and spiritual health of my patients. The toll that toxic stress takes is called weathering. The term “weathering” was coined by Dr. Arline Geronimus. It is a metaphor for how stress caused by everyday racism shapes or weathers the body.

Weathering describes the geological concept of imperceptible erosion of rock by the elements over time. Rock does not have a reprieve from these elements, and with time, each raindrop and melt/freeze cycle contributes to the mountain’s size diminishing.

In humans, it is easy to imagine that the constant background stress of living in a racialized society could push one’s nervous system into a consistent low-grade fight-or-flight response. This results in elevated stress hormones that raise blood pressure and glucose levels, and biochemical cascades of inflammation. These changes would cause people of color to experience a greater disease burden at a younger age and a lower life expectancy compared to white people. Geronimus demonstrated that race-based disparities in health outcomes persist even when adjustments are made for socioeconomic status.

I hypothesize that the weathering phenomenon affects LGBTQIA+ people as well. Homophobia and transphobia are pervasive in our society, as seen by the increased prevalence of laws making gender-affirming health care illegal, dictating what bathrooms people can use, banning books, and censoring curricula. The constantly changing legal landscape often engenders a background level of worry and hypervigilance for LGBTQIA+ people — which can increase stress hormones and inflammatory cascades, as it does for people of color. Again, this likely results in increased disease burden and diminished life expectancy.

What can we in the medical profession do to address toxic weathering? I believe that individuals in the privileged majority must educate themselves, listen, and speak up against injustice. Medical professionals must take the lead and learn to sensitively ask patients how racism, homophobia, and transphobia affect their daily lives — and then listen without judgment — because those in the privileged majority are not the experts. We must explain that we ask because we know there are physical and emotional health consequences of living in our society as people of color and LGBTQIA+ people.

All clinicians, regardless of specialty, should bear in mind, and explore when appropriate, that people of color and LGBTQIA+ patients likely have suffered trauma inflicted BY the medical system. We must commit to redressing this. We must check our biases, asking ourselves whether we would treat a white or cis or heterosexual patient differently in medical care. In our efforts to create a safe space, we follow the patient’s lead, knowing that trust must be earned.

When people of color and LGBTQIA+ patients present for care, we need to take their symptoms seriously and search for physical causes of illness, because the effects of toxic weathering may increase disease burden for these populations relative to white, cis, het society. We need to pay MORE attention when we see people of color and LGBTQIA+ patients. Hopefully, this collective effort will begin to right centuries of wrongs.

Pam Adelstein is a family physician who works in a community health center that serves LGBTQIA+ and people of color.

Illustration by April Brust