The following is an excerpt from Elderhood.

I refilled my coffee cup and checked my pager to make sure its batteries were charged. So far, my on-call weekend had been eerily quiet, and I wondered if I’d missed calls. The pager was in my hand when it alarmed, its glowing green display showing a patient’s name, record number and contact information, the caller’s name, and the reason for the call. In most practices, the caller is the patient. In geriatrics, it’s not uncommonly someone else — an adult child, hired caregiver, friend, or visiting nurse. On this particular message, in addition to a daughter caller, the most notable words were: mother not herself and worried.

After I dialed, Veronica, the daughter, answered almost immediately. “Thank you for calling so quickly.” Her words, although measured and polite, carried an unmistakable undertone of urgency and concern. “I don’t know if it’s anything. The paramedics were here last night — early this morning — and they didn’t think so. I’m probably overreacting.”

I said that if something was worrying her, that was a good reason to call, and I asked her to tell me what was going on.

“My mother Lynne and I had a special event planned for yesterday. She was looking forward to it all week. We kept talking about it. We’d even discussed what she’d wear and what time we’d leave. And then yesterday morning she didn’t get up. She just didn’t seem interested in going. It was really strange. She did get up eventually, but all day she just didn’t seem like herself. I asked if she felt sick but she said no. She didn’t even mention the thing we were supposed to be doing. I told her I thought we should go to [the ER], but she said no, that there was no need, and she didn’t want to go.”

At this point, I couldn’t resist the urge to interrupt. “What’s she like usually? Is she healthy?”

“Oh, she’s great,” Veronica said. “She has some problems but nothing too serious — blood pressure, heart disease, arthritis, that sort of thing. That’s why she sees Dr. P., but she’s in good shape, mentally and physically. We just live together because we like each other.”

That made me smile. Meanwhile, I debated whether to ask for a few more specifics. Sometimes families and doctors have different notions of what constitutes minor and major health issues. In theory, I could get the essentials of her medical history from the EHR. In practice, getting into the record from afar required making my way through a series of password-protected firewalls, and I wasn’t in yet. Still, something new was going on with Lynne, and I needed to prioritize determining its urgency.

I asked Veronica to tell me more. “Is she doing basic things the way she usually does them? Eating? Walking? Talking …?”

“She had a good breakfast and some lunch yesterday. Not too much dinner, but she was tired. We did go out for a walk in the afternoon. I thought it was strange that she wanted to walk but didn’t want to go to the event.” I relaxed a little. If Lynne was seriously ill, she probably wouldn’t have much appetite or enough strength to go out and walk.

“She’s just kind of slow,” Veronica added. “And vague.”

I unrelaxed. “Has she ever been like that before?”

“Never.”

At this point I needed to figure out whether there was a brain problem specifically or if the change more likely represented delirium. A seriously ill person of any age can develop delirium, but it occurs most commonly in older patients, especially if they have underlying dementia. Delirium can develop as a result of something as seemingly minor as catching a cold or taking an OTC pill. It can happen because of major or minor infections, surgery, a broken bone, a medication, a new environment, and almost anything else.

I asked Veronica whether her mother’s speech made sense. “The paramedics asked her a bunch of questions about her name, my name, the date and year, how old she is, where we live, and she got them all right. She’s communicating, just slowly. Our walk was slow, too.”

Because of age-related differences in disease presentation, doctors often get more relevant and helpful information from old patients when we ask about changes in basic activities. Such questions resemble those used by pediatricians about eating, sleeping, peeing, pooping, and playing. In geriatrics, we use the same first four and add to them questions about mobility, pain, mood, behavior, and how they spend their days. The point is not to infantilize old people but to recognize the biological reality that at both ends of the life span, diseases are less likely to manifest in the ways we define as “standard” and more likely to show up as a change in basic function.

“Mom got worse last night,” said Veronica. “She was getting ready for bed and not wearing her pajama bottoms. She never walks around naked. At around 10, before I went to sleep, I saw the light in the bathroom. When I got up a little before one, it was still on and Mom was just standing there. She seemed disoriented and I thought maybe she’d been there that whole time. That’s when I called 911.” She paused as if expecting me to admonish her.

...

“You weren’t wrong,” I told her.

Shaming a patient’s concerned relative is, under any circumstance, unacceptable professional behavior. Next, she said [the paramedics] looked through her mother’s medications. On my end, I scrolled down Lynne’s medication list in our EHR. But what appears on our official logs and what a patient is actually taking often differ, so I also asked Veronica what her mother was on and if there had been any recent changes.

Veronica read me the list, then said, “The paramedics checked all the bottles and said she seemed to be taking everything except the antidepressant. I guess she stopped that three weeks ago, though I didn’t know about it. They said that was it. That was the problem. They gave her a pill at 2:30 this morning and told us both to go back to bed.”

Suddenly stopping an antidepressant can cause a bad reaction, but the withdrawal would manifest gradually over days, not suddenly three weeks later. Veronica continued, saying that this morning her mother was still not herself.

I started a review of symptoms, questions about her body from head to toe, grouping organs by location, such as eyes, ears, nose, and throat, and physiological role, such as cardiovascular or nervous system. Veronica answered some questions herself but mostly she repeated my queries to her mother. I could hear faint nos periodically in the background. No fever, cough, shortness of breath, increased urination or new incontinence. No chest pain, weakness in a limb, changed vision, speech, or swallowing. No belly pain, nausea, or vomiting. Some diarrhea for a few weeks, but that happened. No blood in her bowel movements.

But then, there it was: Lynne had a headache, and not just any headache. The worst headache of her life. She described it as a 10 on a scale of one to 10, where 10 is the most severe pain imaginable. That she said she felt fine while experiencing that kind of pain was another worrisome clue.

I told Veronica that we needed to get her mother to the ED right away. We agreed that Veronica would phone for the ambulance and I’d call ahead to the hospital. Before we hung up, I told her how glad I was that she had called, that her instincts were just right, and that her mother was lucky to have such a perceptive and persistent daughter. I also promised to give the paramedics feedback on their care of her mother. At the very least, they needed to know that most older adults are not confused, that sudden confusion always indicates a problem in need of medical attention, and that ignoring a family member’s concerns is bad medicine.

After a few hours, I logged back into the medical record. On the CAT scan of Lynne’s brain, it looked as if someone had spilled black ink onto a white picture. Sometime between when she’d gone to bed Friday night and when her daughter had gone into her bedroom on Saturday morning, she’d begun bleeding into her head. By Sunday morning, she’d had a large hemorrhagic stroke.

Three months later, I recognized Veronica’s name in my inbox. In her message, she apologized for not writing sooner and thanked me for my help and support. She gave me an update on her mother, who was finally back home: “It has been a difficult journey, but I was able to come home this afternoon and give my Mom a hug. I was able to ask her what she might like for dinner. I was able to plan her 80th birthday celebration in September.” Lynne was changed by the stroke, but her life still provided pleasure and meaning to them both.

Louise Aronson, MD, MFA, is a geriatrician, writer, and professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco. The author of Elderhood and A History of the Present Illness, she is a regular contributor to the New York Times and the New England Journal of Medicine among other publications. Recognition of Louise’s work includes a MacDowell fellowship, four Pushcart nominations, the American Geriatrics Society Clinician-Teacher of the Year award, and a Gold Professorship for Humanism in Medicine.

All names and identifying information have been modified to protect patient privacy. This excerpt has been slightly modified from Elderhood: Redefining Aging, Transforming Medicine, Reimagining Life.

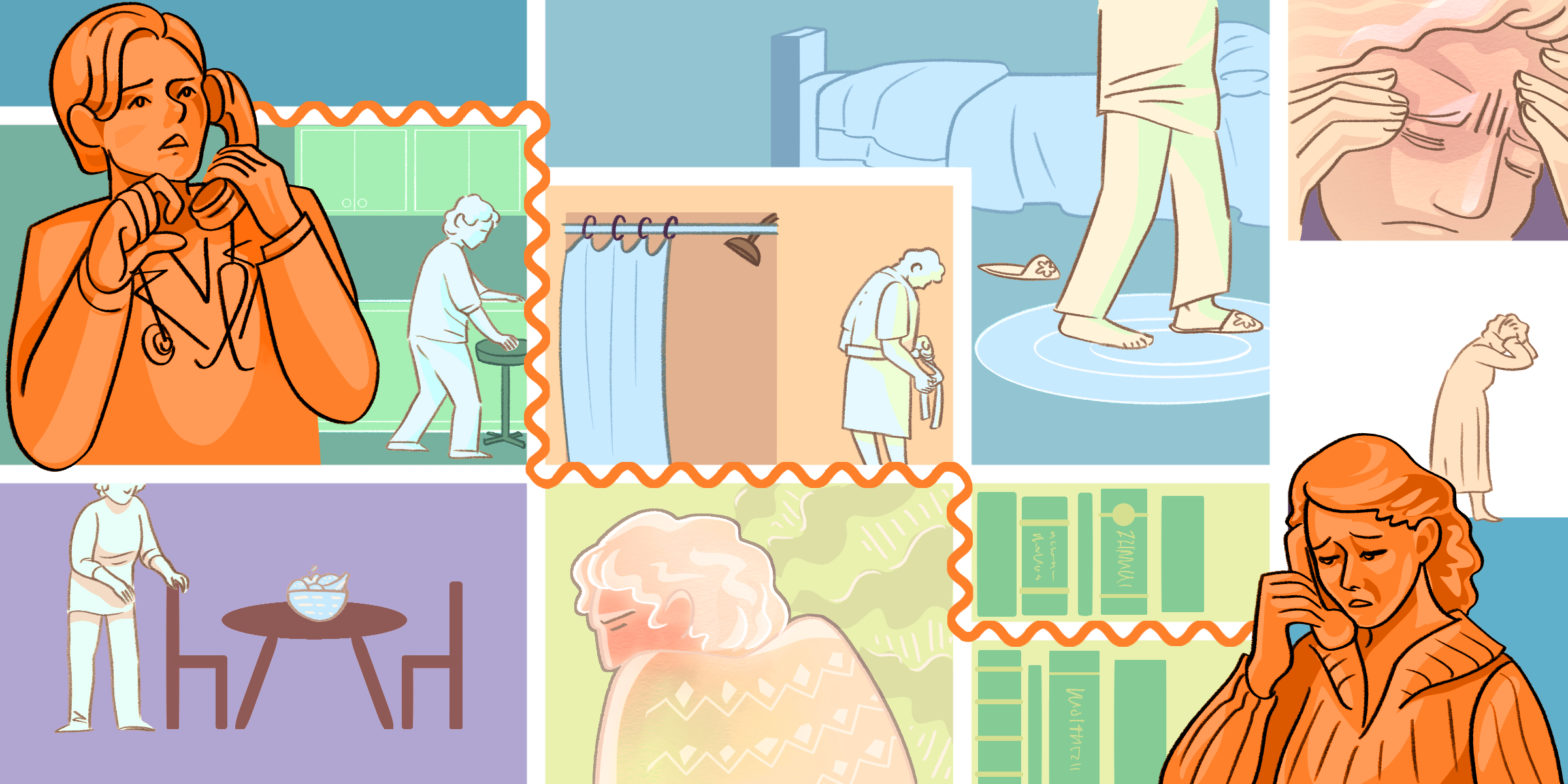

Illustration by April Brust