“Why do I always see a new doctor every time I’m here?” From her wheelchair in the corner of the room, Ruth, my last patient of the afternoon clinic, sighed. At 62 years old, she had a common trifecta of chronic medical conditions: hypertension, Type 2 diabetes, and hyperlipidemia. Reviewing her records before our appointment, I saw that none of her conditions were well controlled. In fact, her chart was flagged with recurrent notes echoing each instance in which she had declined recommended medications, was “lost to follow up” after referrals, or simply did not make it to her scheduled appointments. She was also uninsured, unemployed, and lacked reliable transportation.

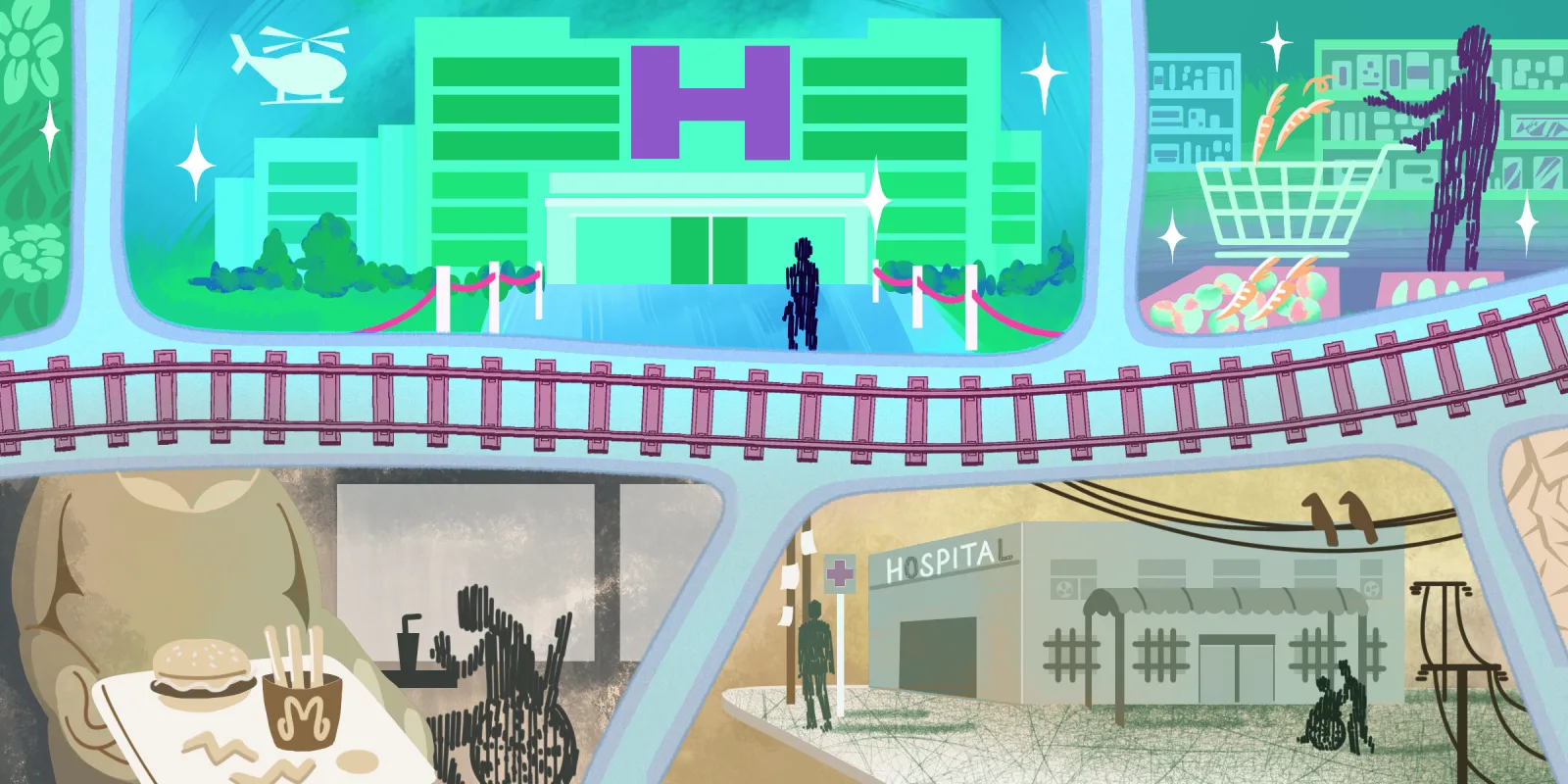

While I wish Ruth’s case represented an outlier, she was one among many patients with similar challenges in this particular clinic, run by one of the largest federally qualified health centers in the country. Here, many of the patients are uninsured and 63% live below the federal poverty line. These patients highlight the unavoidable role of social determinants of health, including education, employment, and income. Although the bulk of my medical training thus far has been focused on the clinical care of patients, it is estimated that clinical care, including access to and quality of care, accounts for only 20% of the modifiable predictors of health. The remaining 80% is largely attributed to socioeconomic factors, physical environment, and health behaviors.

Given the magnitude of structural social forces, I admit to struggling with frustration and hopelessness in what feel like demoralizing dilemmas. I have treated patients experiencing homelessness, only to send them back to the same conditions that contributed to their disease. I have also encountered patients with complications from diseases that could have been prevented if they only had appropriate access to health care. But, stable housing and poverty seem far beyond my control as a physician, even though their impact on my patients’ health is undeniable. How can I fix societal barriers in a single visit when the inequities in our health care system are deeply rooted?

I felt my brow furrowing as I listened to Ruth share her experiences in clinic: with every visit, she saw a new clinician, and with each she felt like she was starting over again. When she was prescribed medications for her blood pressure or diabetes, she discarded them out of fear of the side effects. She had not trusted any of her doctors enough to disclose her concerns because she hadn’t built a relationship with them and wasn’t sure she’d see them the next time she visited. Further, each new prescription represented a financial trade off, forcing her to pick between medications – all necessary – based on her budget for the month.

Her chart had not communicated any of this. While her nonadherence to treatment and missed appointments were documented, neither were due to ignorance or disregard of medical care. Rather, Ruth was constrained by complicated, interconnected barriers in a challenging social environment — and though I could not fix those barriers in our clinic visit, I could better understand her needs and at least try to provide effective care within our limitations. I started by acknowledging her fear of side effects: together, we formed a plan for treating her hypertension that she was comfortable with, starting with a single well-tolerated medication.

“This may not be enough to get your blood pressure to our goal, but there are other generic medications, even combination pills, that are more affordable as the next step,” I suggested.

“You’re the first person to explain these medicines to me,” she said. “In my other visits, I would just nod and go along with whatever the doctor gave me, knowing I would never pick up the meds.” Ruth promised that she would at least try the medications this time.

“Can I come see you again?” she asked. As we scheduled her follow-up appointment, I felt a budding sense of hope. Although I did not solve her financial or housing difficulties, recognizing those barriers in her life helped me provide care more tailored to her circumstances. In the end, our clinical care of patients does not exist in a vacuum, and exploring social determinants of health is essential in contextualizing our care of patients in need.

Have you treated patients whose fractured care produced non-adherence? How did you de-escalate the damage? Share your strategies in the comments.

Evaline Cheng is an internal medicine resident at the University of California, Los Angeles and an aspiring cardiologist who seeks to improve the delivery of cardiovascular care. As a lifelong journal writer, she now shares stories of narrative medicine to connect and project voices otherwise unheard. Dr. Cheng is a 2021–2022 Doximity Op-Med Fellow.

All names and identifying information have been modified to protect patient privacy.

Illustration by April Brust