When I began my first job out of training, I entered a busy hospital practice and immediately discovered problems. Communication gaps between departments, for example, led to disjointed, broken patient care. My visceral reaction was to approach these “problems” as a medical scientist, by diagnosing and recommending the appropriate treatment. I went to my first department meeting and presented a passionate plea that a problem existed and relentlessly connected the dots to the eventual downstream patient harm. My comments were received with universal agreement by all in attendance. I felt good about myself as I viewed myself as a patient advocate. In my mind, I had achieved the noble status of a physician that could affect change. Notwithstanding my sense of accomplishment, there was a small problem. Nothing actually changed after the meeting. I had confused hollow words of support as signals of eventual improvement.

After months without any attention or change, I became frustrated and discussed my experiences with my colleagues. I learned that many were not surprised and almost amused at my naivete in thinking I could improve anything. “Nothing changes” was the consistent message I would hear; the system was hardwired in its current state, unable to move unless it was forced by extreme situations. There was a sizable cohort of physicians that had simply given up on presenting ideas or advocating for any improvement. They consistently viewed department meetings as empty exercises that simply created the image of a responsive forum. This rather bleak view seemed to permeate most, if not all, of the discussions with my colleagues.

I found this perspective enigmatic, as these pessimistic opinions were maintained by otherwise exceptional physicians who were amazing within the scope of their practices. They were motivated to deliver amazing care to their patients but would immediately withdraw at the challenge to address a systemwide challenge in the hospital. In my naivete, I initially saw their relative apathy as a form of wisdom, thinking that I would eventually approach the same problem with the same indifference. Now I realize it wasn’t indifference, but a guard against being disappointed.

After reflecting on the different approaches by myself and some of my colleagues, I fundamentally believe our passion to treat patients spills over and bleeds into our zeal to improve broken processes in our various health care systems. This passion, though a great motivator, can misfire and present blinders to the slow, difficult process required to engage change at a global level. Moreover, there is an added side effect of the enthusiastic drive to fix: you get burned and withdraw. Despite their indifference at the surface, my “detached” colleagues were actually no less passionate. They were just more guarded — and realistic.

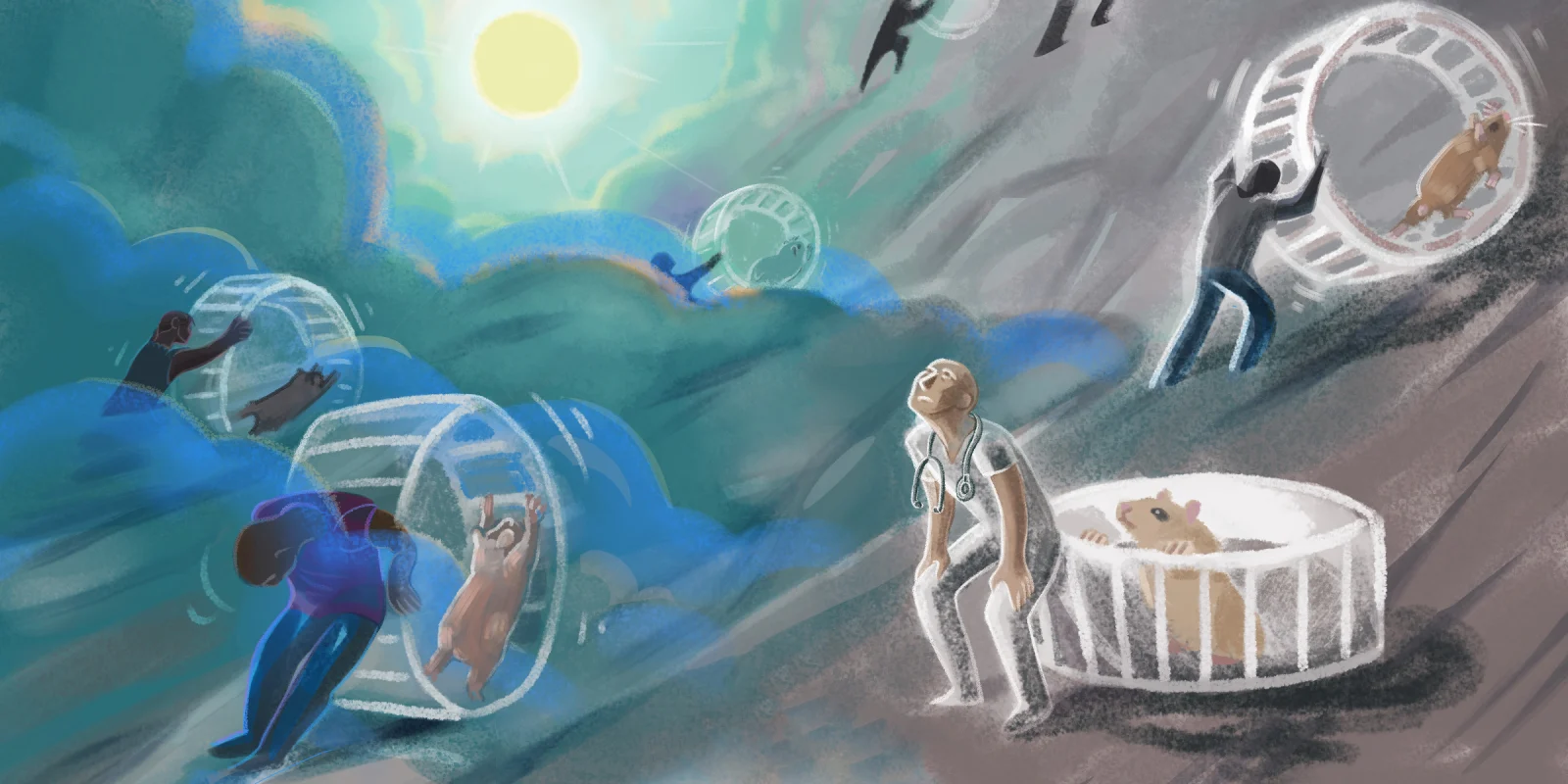

If I want to change the way I make decisions, I only have to convince myself. At a systemic scale, change requires a different effort. Throughout my training, I was hardwired to make clinical decisions confidently and efficiently. Moreover, if I discovered a potential problem in a patient’s care, I would approach that problem with the passion demonstrated by my various mentors over the years. I was righting a wrong. Unfortunately, this approach and, more importantly, mindset, does not work in dealing with larger challenges across an enterprise. Change is an inherently slow process and requires the buy-in of multiple stakeholders. If the approach to change management were graphed, I believe most physicians would fall into a bimodal distribution, with one peak representing overexuberance and the other peak as outward indifference. Both peaks are ineffective. Change happens in the middle, with persistence.

I have noticed a few physicians are masters of change. They are balanced and methodical in their approach. Their passion may motivate, but their pragmatism governs their words and actions. Instead of running to the boss and yelling about the etiology of problems, they patiently understand the differences of opinion and work quietly to bridge the gap and develop a consensus. Their timeline is not days but months. They encourage without getting frustrated or demoralized. They approach the challenge of organizational change with the same curiosity they approach patient care. While many remain fixed on their self-justified peaks, these masters of change lie in the middle, quietly tackling our system’s thorny issues.

In my personal evolution, I must often suspend my reflexive approach to problem-solving ingrained by my training. I must freeze my desire to immediately attack and enucleate every systemic problem that I encounter, expecting immediate solutions. I no longer view these challenges with frustration or capitulation. I consciously seek out the middle path, quietly and steadfastly working to build bridges and develop understanding instead of judgement. Patience, in this regard, might represent the beginning of wisdom.

How do you stay motivated in improving our health care system? Share your inspirations in the comments.

Dr. Chirag Parghi is a board-certified radiologist with fellowship training in breast Imaging and currently serving as the Interim Chief Medical Officer of Solis Mammography. His clinical interests are focused on the early detection of breast cancer. Dr. Parghi has been practicing radiology in the greater Houston area for 8 years, and obtained his MBA from University of Houston. He is a 2021–2022 Doximity Op-Med Fellow.

Illustration by April Brust