He looked down at me. “You mean you really haven’t done one of these before?”

He looked down at me. “You mean you really haven’t done one of these before?”

I had begun my third year of medical school with the notion that all patients were unique and all doctors more or less the same, but after a tour through only a few rotations, I had been thoroughly disabused of the latter. Every attending I worked with seemed to have been formed in a world only remotely comprehensible. Some seemed forged in a world of fire, such as Dr. J, a five-foot-two attending who hopped around the halls during rounds, asking questions to the air and then answering them without hesitation. Some attendings seemed frozen in a world of ice, such as Dr. R who led table rounds slouched pseudo-moribund in his chair, lifting his eyes over his well-cultured mustache only to peer in silent rebuke at an H&P gone hopelessly off the rails.

Dr. L the neurologist was of yet another world, gripping his bamboo queen square reflex hammer in his folded arms.

“Not even one?”

The contrast of his spare body and thin reflex hammer leaning over me in my short coat, could not have been more stark. Every piece of medical equipment I owned dangled erratically out of my pockets.

“That’s the problem with the training today, all electronics and no action. I bet you can tell me what gene comes from what chromosome and look up differentials that do not exist, need not exist, and have never existed in any real patient (he motioned toward the phone in the pocket) but no student I meet these days has enough sense to keep his fingers off the sharp end of a needle. Let me tell you, when I was on the wards, I had to use this (points to head) and these (holds up fingers) to make my patients better. Do you know how many spinal taps I did as a student at the L--------- County Hospital? I did 17 in one day! Writhing infants. Drunks. Cirrhotics. Psychotics. Unbalanced geriatrics with more barnacles between their spinous processes than there are on the hull of the U.S.S. Maine. It did not matter. One after the other. Pop. Pop. Pop.” He snap, snap, snapped. I’d have the kit out, the spinal ready, the manometer, and (another snap) I’d have it all done in under a minute. Do you think we needed fluoroscopy? Do you think we asked the neurosurgery resident in the hall for a hand? This is what training is. This is what your hands are for, not for poking at a screen all day long, liking Twitter videos in the cafeteria, hiding from patients.”

We walked down the hall toward our target thecal sac. “There was one time, granted, I had a hell of a time getting the juice. There was this one time (armspan)... but that’s what you do as a medical student, you learn by doing. Well, the first needle I tried was just too short. I was just floating around in there, nothing. The second needle I tried, the 15 cm, was just as bad. I was hubbed and I couldn’t even scratch the edge of a spinous process. So what would you do then?”

Blank stare.

“Review the imaging? Of course you would. That’s what everyone does these days. Look at the CT. Look at the MRI. We didn’t have those in those days. MRI machines were kept in jet hangars. So you’re aiming at the right spot: stylet in, stylet out, nothing. What would you do then?

“I suppose I would go get my intern.”

“What are you, a puppy? Why would you let a learning opportunity slip by? But let me tell you what I did. I went to the storage closet and found the longest 22 gauge needle I could find...26 cm. Have you seen one of these? (another armspan motion). It did the trick. I found the spot in no time at all (twisting finger motion) and not a drop of blood. It was like a water faucet. Three tubes in 10 seconds.”

We had reached the room. It wasn’t that far a walk, but a bead of perspiration had appeared on my forehead. Dr. L gave me a pat on the back before I went in. I introduced myself, took a minute to explain the procedure, went through each paragraph of the consent form, and then rolled the patient into a right lateral decubitus. Then I went back out to the hall to look for Dr. L. He was leaning over the nurses’ station, hammer dangling from a loop in his white coat. He walked over and held out his hand. When I looked perplexed, his face fell.

“Where are they?”

“Where are what?”

“The tubes. The juice.”

“I just finished with consent. The tray is in there, but I was going to go look for a gown and a faceshield and…”

His face continued to fall and his shoulders dropped.

“Were you planning on licking your fingers? I once worked at a hospital where all we had were latex gloves and I can’t remember anyone getting meningitis who didn’t have it already. Let’s not delay this patient’s diagnosis anymore. Time is brain. Remember that. Now you tell me that you’ve seen one on a YouTube video (which I had not) — let’s see you do one.”

We went in there and I unfolded the tray with painfully careful torpidity. Dr. L’s agitation increased exponentially by the second.

“You keep the skin clean and keep the needle clean. Get the fluid and get out. You probably don’t even really need sterile gloves if you know what you’re doing, but maybe it’s best that you put some on.”

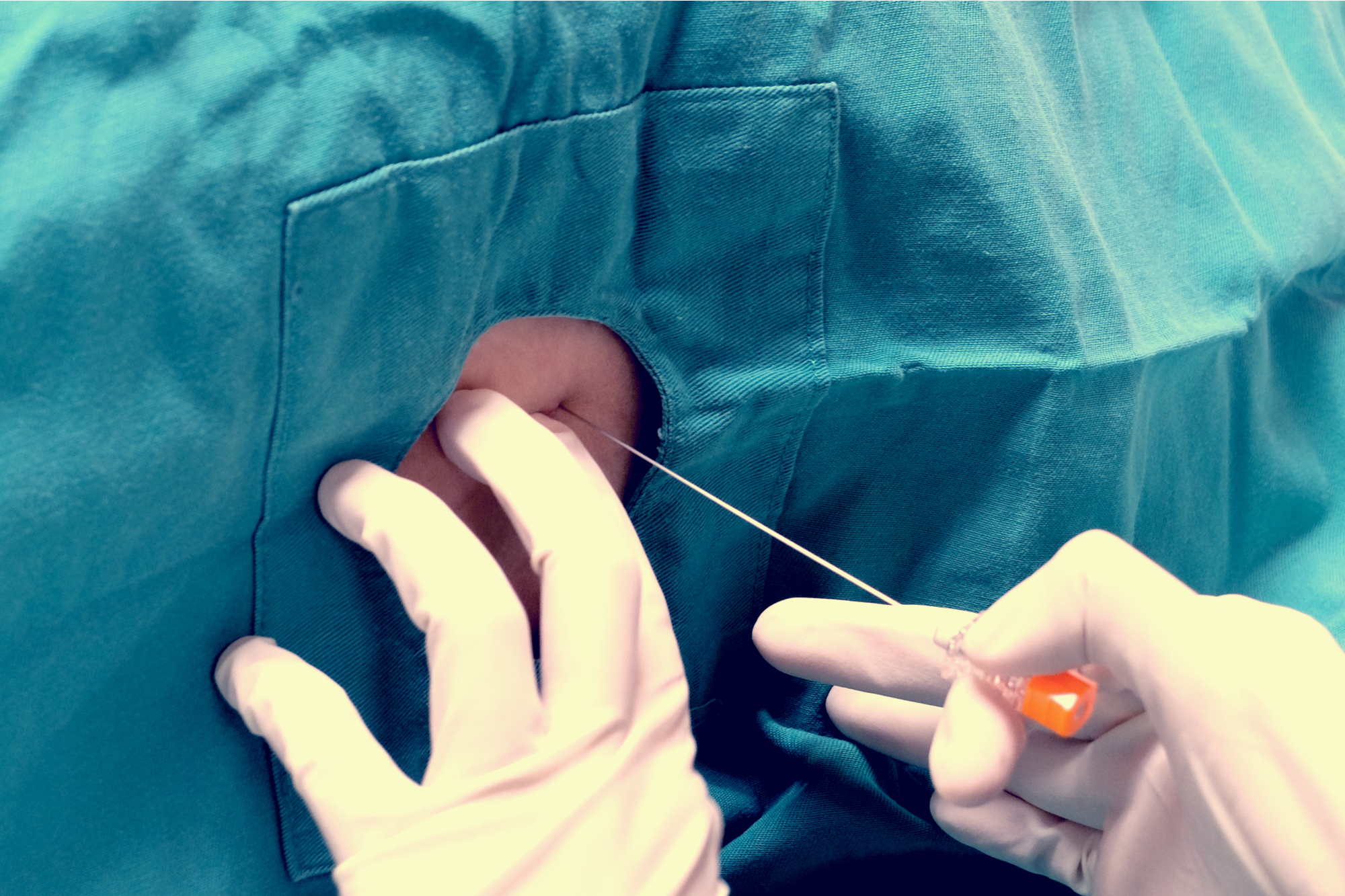

Needle tip just below the surface, I hesitated, imaging where the umbilicus might be on the other side. One drop of blood appeared at the entry site.

“Here, just hand it to me,” he said and snapped a pair of gloves on.

Matt Morgan is an assistant professor of clinical radiology at the University of Pennsylvania. He has performed hundreds of percutaneous procedures (and counting) and enjoys teaching residents and fellows.

Image by Casa nayafana / Shutterstock