Dr. Sam Rodriguez is a Pediatric Anesthesiologist at Stanford Children’s Hospital. He is the Founder and Co-Director of the CHARIOT Program, which uses emerging technologies like virtual reality, augmented reality, and interactive video games to treat children undergoing procedures. He is also deeply involved in medical humanities education at Stanford Medical School and is an artist himself.

As a pre-medical student at Washington University in St. Louis, Dr. Rodriguez started taking some of his first painting classes. He found he really enjoyed them even if he “wasn’t that good at the time.” In medical school at Penn, he took advanced figure drawing and oil painting classes at night. As he refined his craft, he starting thinking more seriously about how he could integrate art and medicine.

“As a resident, I began doing medical illustration on the side. I had to learn digital illustration software and skills since I had been trained in oil painting. It was a great skill set to learn at the time.” He continued with medical illustration well into his career, but recently cut back due to other responsibilities in education, research, and clinical practice.

“During my residency, I became involved with the Training the Eye class at Harvard Medical School, which has been around for over 10 years or so. I started working on the drawing curriculum and was able to push that forward during my time there.”

He came to Stanford three years ago and now teaches a similar class for medical students called The Art of Observation: Enhancing Clinical Skills through Visual Analysis. The course seeks to enhance medical students’ observational and descriptive abilities by analyzing works in Stanford museums with guidance from Stanford Art History PhD candidates. Students discuss their findings with medical school faculty after, in a clinical correlate to each gallery session. The course was so popular that they have created a version for undergraduate students as well.

PP: Could you tell us about the medical humanities class you teach at Stanford? What are the goals behind the class?

SR: We have students go to Cantor Arts Center and we put them in groups 5–8 students — which is similar to the numbers of people you would round with on the wards. We have them come up with hypotheses and alternate hypotheses of what may be going on in paintings around the museum. We actually want our students to politely argue about what may be going on in the painting because everyone has a different perspective.

We also bring in speakers from various specialties for the clinical portion. One speaker we have almost every year is a Dermatologist, who has students describe specific lesions in detail. The idea is that if they could do this over the phone or email, they could find a specialist who was able to diagnose the lesion. It really helps students’ descriptive abilities. The speakers are not restricted to Dermatology, we also have lecturers from Neurology, Radiology, and Surgery.

We try to promote the importance of narrative and story in medicine — and understand how outside influences may affect a patient’s behavior. For example, if a patient has trouble getting to the pharmacy to pick up a medication or has 15 medications and doesn’t know when to take them, it may manifest as non-cooperative behavior. We want students to understand external factors for patients outside of the disease state.

PP: Do you see improvement in students’ observation skills at the end of the quarter?

SR: We see an improvement in students’ ability to articulate what is going on in a painting and speaking about art with each other. We see a qualitative increase in students’ observational skills, but it is very challenging for us to quantify this improvement. Other schools have carried out studies on this type of class. They’ve found a correlation with better observational skills in students going through these classes.

It helps students become more comfortable with situations when there may not be an answer or may be multiple solutions. It helps them become better at being comfortable in situations where they do not know the answer.

PP: Do you think we need to better promote creativity or art in medical education?

SR: I think the term art silos creativity to the visual arts. The term we use to encompass creativity is “medical humanities” and this includes things like literature, theater, performing arts, in addition to visual arts. In recent years, I think medicine has realized the importance of humanities education in medicine. As far as the medical humanities are concerned, I think we are headed in the right direction but there is still a lot to be done. At Stanford, many humanities classes are in the elective realm meaning that people need to choose or elect to take these in addition to the rest of the medical curriculum.

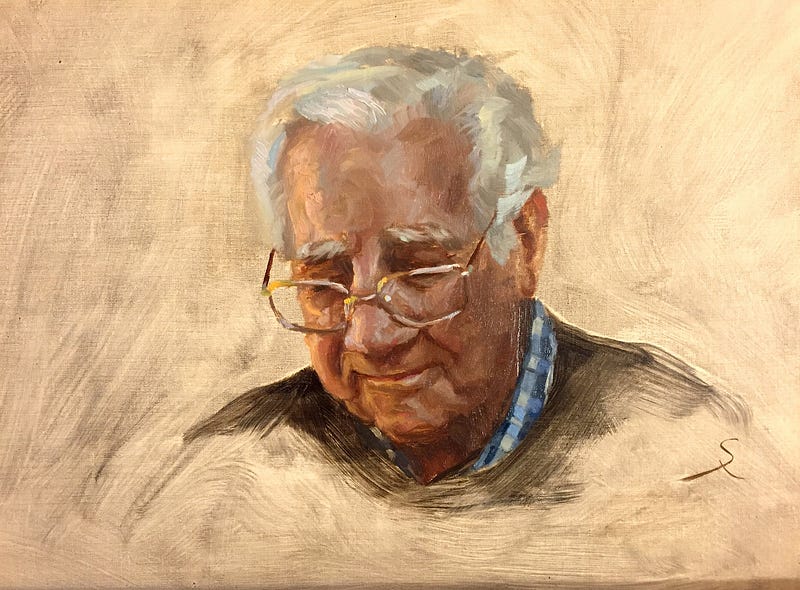

PP: I was looking over your portfolio and notice you mostly paint portraits and the OR, presumably because you’re an Anesthesiologist. What do you like about painting OR scapes and people?

SR: As a physician, people are my focus. It is very satisfying to be able to capture someone in a portrait. There is something special when someone says, “you’ve really captured that expression or person.” I really enjoy painting people, even though my wife would prefer landscapes because they’re better to have around the house than random people staring at her while she eats.

I do want to say thought that portraits are one of the hardest areas to get into because we are all experts on the human face, even if we haven’t formally studied it. Even little kids can tell if something is off in a portrait. They may not be able to articulate it, but they know it looks weird. I’ve spent 30 hours on a portrait and had to scrap it because the nose is a bit off. There’s a quote from one of my favorite American painters, John Singer Sargent, in reference to painting people he knows that goes something like “every time I paint a portrait, I lose a friend.” I think there’s some truth to that.

Dr. Rodriguez’s creativity is not limited to medical illustration and painting. During his time at Stanford, he has founded the CHARIOT program, which stands for Childhood Anxiety Reduction Through Innovation and Technology. He works with colleagues and a team of software engineers to create innovative ways to put children at ease before undergoing anesthesia or a procedure.

PP: Can you tell us about the CHARIOT program and specifically your work on BERT?

SR: Oh yeah, so much fun! The BERT project, which stands for Bedside Entertainment and Relaxation Theater, is a screen-projector unit that allows kids to watch shows while they’re being transported through the hospital or before surgery. We worked on the design for a long, long time to make sure it was infection control compliant. The screen is mounted on the foot of the stretcher while a small projector is mounted at the head of the stretcher. We worked with colleagues at Stanford and took advantage of our location in Silicon Valley to collaborate with programmers. There are a number of interactive games kids can play. One is named “Sevo the Dragon.” Sevo, the animated dragon breathes fire every time a child breathes in, either oxygen or eventually anesthesia gas in order to cook a piece of a food, that the child gets to pick.

At this point, over 1,000 patients have been treated using the BERT system. This is better for kids because it reduces anxiety and studies have shown that children need less sedative medications before surgery when the BERT system was implemented. It helps kids become more cooperative and it’s fun! After we implemented BERT in clinical practice, we saw a bump in patient satisfaction scores as well.

PP: Are there any new projects you’re currently working on as part of the CHARIOT program?

SR: In 2016 we started moving into the realm of virtual reality. We wanted to find a way to use VR to reduce anxiety and increase cooperativity in kids. I’ve had the opportunity to translate some of my creative skills to brainstorming new video game ideas for kids. I’m not doing any animation because there are people who are much much better than me. I sometimes sketch the initial concept art for the video games. My colleagues and I are working more as producers to come up with ideas for VR games. We have two ongoing clinical trials trying to quantify the effect of VR as a tool to reduce anxiety in children. The programmers have been so great and I think it has been very rewarding for them to build something that is directly impacting children’s lives in a positive way.