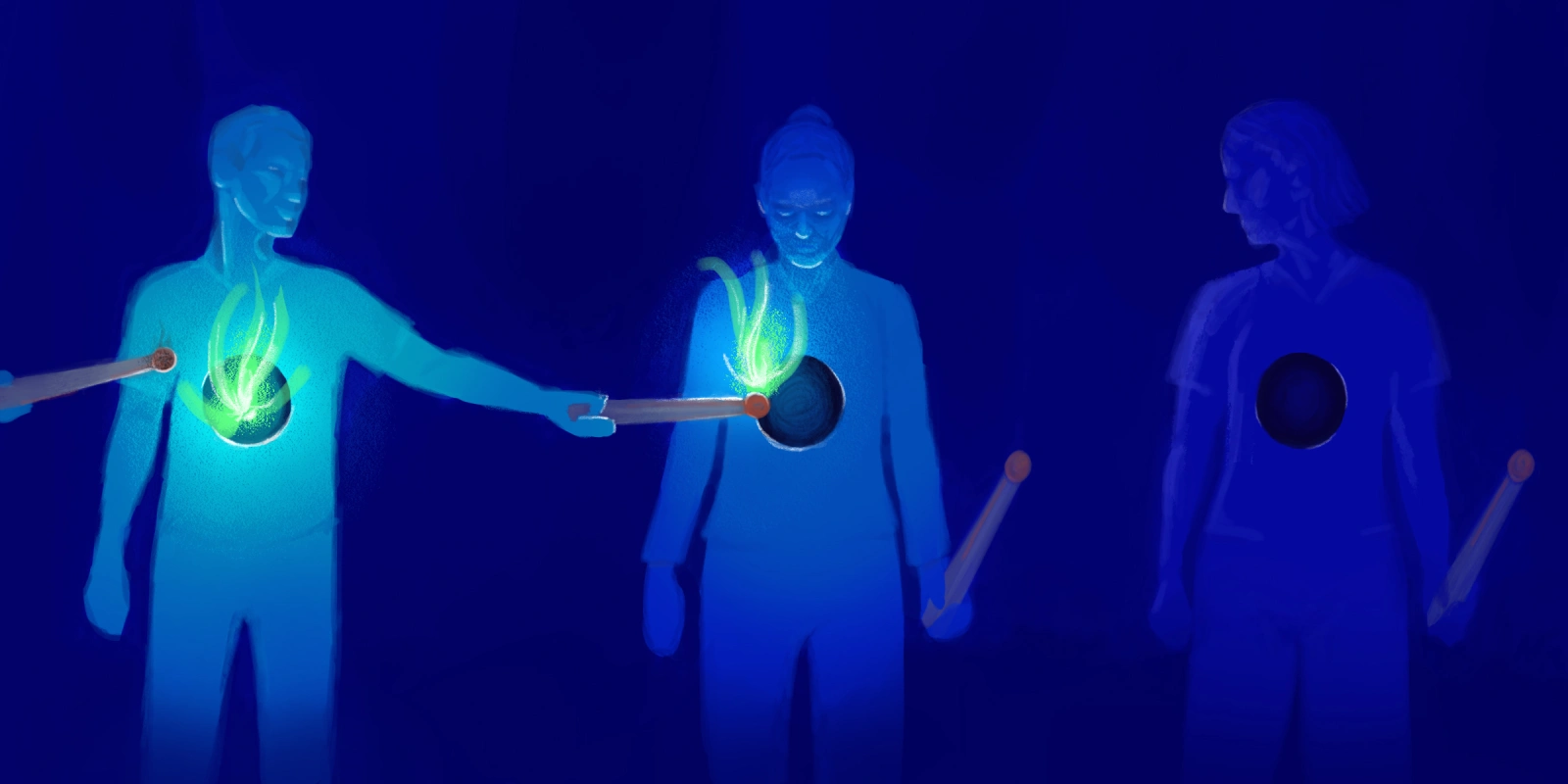

I’m sure you’ve heard the expression, “I don’t know what I want, but I will know when I see it.” We may be drawn to certain people who show passion, interest in various topics, or are enthusiastic about their hobbies or jobs — they have a spark in them. Then there are those who seem to be merely existing, just getting through their days: their spark is dim, or fading away. In psychiatry, one of our goals is to rekindle that spark, to allow our patients to regain their passion for life, and distance themselves from merely existing day to day. If we are lucky, we may even be present when that shift occurs, when our patients begin the journey to reclaim their spark — the force that drives us to excel, the ember that fuels our life force.

However, sparks need tending, like the embers of a fire. Why do we all know the term “burnout?” Despite those long days in the office, hospital, or OR, we come back for more. Our work takes its toll on our lives and relationships. At our best, we share the burdens our patients face, which then works to snuff out our flames over time. Sometimes we can focus this pressure, and stir the fire back to life, but it’s an ongoing battle, and one that I’ve felt I’ve sometimes lost. But for one patient, I was able to help her find her spark again.

I recall a young woman whom I had seen as a patient for a couple of years. She initially came in with her stepfather, with complaints of moodiness, depression, and poor sleep patterns. She was a bright young person, who had great academic performance up until her junior year of high school, when she became increasingly withdrawn, isolating herself from her family and friends. Attendance dropped off, and she spent most of her time in her room. She was no longer the athlete that she had been, with competitive standing on her high school’s swim team.

The initial meetings we had were tense, as she said very little, and her stepfather, who had tried his best to help his daughter, had obviously given up. He simply stared at me, unblinking, waiting for the “magic pills” I had prescribed to take effect. Very little progress was being made. I stressed to both of them that the medication was simply a tool, a stepping stone back to a better psychological baseline, but no tool would do the job on its own. It would take the person to make the tool effective and to maximize its impact in their recovery. They both seemed to understand this, but every time, it was the same report: limited response if any to the medication, and could we possibly try something else?

Until one visit. The patient and her stepfather arrived on time, and the meeting progressed as slowly as any had been before this one. I reiterated that we needed to look at the meds as tools, etc., without any response.

Silence.

“Look,” I said warily, “we have to determine what it is that you want, what you are looking for. What are your expectations here, what is it that you need, and can I provide it?”

The patient lifted her gaze to me. “I just want to feel normal again, that’s all. I used to be so happy and felt like I had direction. Now I just don’t know. I wander around a bit, I guess. I am not so sad, just bored, and not happy.”

I let quiet fill the room for a moment, then said, “I’d doubt there wasn’t a person on the planet who hasn’t felt lost from time to time, or felt like they had no direction in the first place. We have to work on it, continuously. Even when we’ve achieved what we thought we wanted, we have to keep working at it to give it value in our lives. There’s no special trick here, but understanding that it will be a lifelong effort.”

She held my gaze. “I lost my drive. Inertia, I think it’s called. Everything was getting harder for me, and I felt overwhelmed, like it would all topple over at any point.” Tears welled in her eyes. Her stepfather stopped staring at me, dropped his crossed arms, and nudged closer to his daughter.

“Now I feel like it’s all too late. I’ve lost too much time.”

I looked at this young woman, soon to graduate high school with average grades, and no other distinguishing features on her resumé. I thought about what I would tell my own daughters, what advice I’d give to my younger self.

“It’s not too late, not by a long shot,” I said. “The most interesting stories are the comeback stories, where someone has faced adversity, overcomes it, and achieves what they worked for, rather than it simply being handed to them. We are lucky to be born with gifts, and what we do with those advantages is how we gift back. It’s not easy, but you have shown you can handle hard work, you just need to prove it to yourself.”

It was tense in the room. She sat back in her seat with a gentle shake of her head and said something quietly to herself. Then, she stood up and, surprisingly, took her stepfather’s hand before she left the office.

Initially, I was worried that I had somehow stepped over a line, perhaps being more of a coach than a clinician. I knew what I said wasn’t necessarily unique, or ground-breaking, but I do think that at the time, for her, it was exactly what she needed to hear. Just as a fire needs tending, our spark, our passions need deliberate and careful upkeep. Fire cannot exist in a vacuum, and our spark’s oxygen, as it were, are those encounters that shape us along the way, allow us to realize our passions.

She showed up for her next visit, and it was like a spring rain had just passed. She smiled shyly as she entered the office, and her stepfather, whom I’d never seen with an expression other than a slightly furrowed brow, was beaming. “She’s killing it. I don’t know how else to say it. We are so proud of her. She is doing extra work to improve her grades and is part of the swim team again. I mean, they let her on halfway through the season! That just doesn’t happen.” I watched the patient as her stepfather was speaking, and there it was, the spark that had gone missing. She’d found it again. No longer did she avoid my line of sight. She met it with confidence, and I truly felt that she would be just fine.

After that meeting, I got one more communication from her. A message through our patient portal, simply saying “Thank you.” Her chart had been forwarded to another practice, in another state, near a small college with a notable swim team. It was all I needed. Something deep within me rustled, started to stir back to life. As much as I played a role in helping her progress, this process added oxygen to my own embers, stoking my passion for medicine.

When I was getting ready for bed that night, going through my normal routine, my wife said, “You’ve been quiet this evening, but you also seem content. It’s nice. I missed that.”

I caught my reflection in the mirror. There it was — the spark.

How did you rediscover your spark? Share in the comments.

Chris van Eyck, DMSc, PA-C, MSHS is a psychiatric physician associate working in psychiatry in Northern Virginia. He is a 2023–2024 Doximity Op-Med Fellow.

All names and identifying information have been modified to protect patient privacy.

Illustration by Diana Connolly