“Can I have a drink of water? What human being hasn’t had a drink in three days?”

“Can I have a drink of water? What human being hasn’t had a drink in three days?”

When I received the news that my paternal grandfather (Chinese: Agong) was diagnosed with stage IV lymphoma, I made it my mission to see him in the hospital the very next day. I decided to prioritize spending time with him over a class on medical ethics, and I promptly made my way into Manhattan, all the while thinking: How could this happen? Why didn’t we get a hold of this earlier?

Ashamed that I frankly didn’t remember much about hematology when my father phoned me the previous night, I sought guidance from the most trusted source in my arsenal: UpToDate. The prognosis did not look promising. My grandfather’s diagnosis came as a surprise to everyone and his deteriorating health over the last few years were ignorantly attributed to the natural processes of old age.

As I arrived in the ICU, I was met with a cacophonous symphony of beeps from vital sign monitors and air flows from mechanical ventilators, contrasted by the calm presence of the medical staff. His room was at the end of the hall. As I made my way past all the critically ill comatose patients, it finally struck me: just how bad was he?

I had visited him weeks ago in his Lower East Side apartment and discussed what I was learning in medical school. He was incredibly frail at the time and the majority of my visit was spent at his bedside where he was reclined, drifting in and out of sleep.

“I want to die. I want to die. I want to die.” As Agong said these words, his right hand grabbed mine and his left hand fiercely pulled at the bedding. I was in absolute shock and his statements shook me to my core. As a medical student, I learned about compassion and tried to implement it in every patient encounter — but for all my exposure, this experience rattled me. At a loss for words, I simply told him to save his energy and rest. The nurse at the door could see that I was upset and mentioned that Agong might be delirious due to the mild sedative he was taking.

Death is a subject most Asian families avoid. Not unlike other cultures, death is met with staunch resistance and denial. Some people even go to extremes, purposefully avoiding close contact and proximity to hospitals, funeral homes, and cemeteries for fear of goading and hastening an inevitable end. However, I chose a career path that handles death frequently, and I believe the losses are just as formative as the wins to shape a compassionate physician.

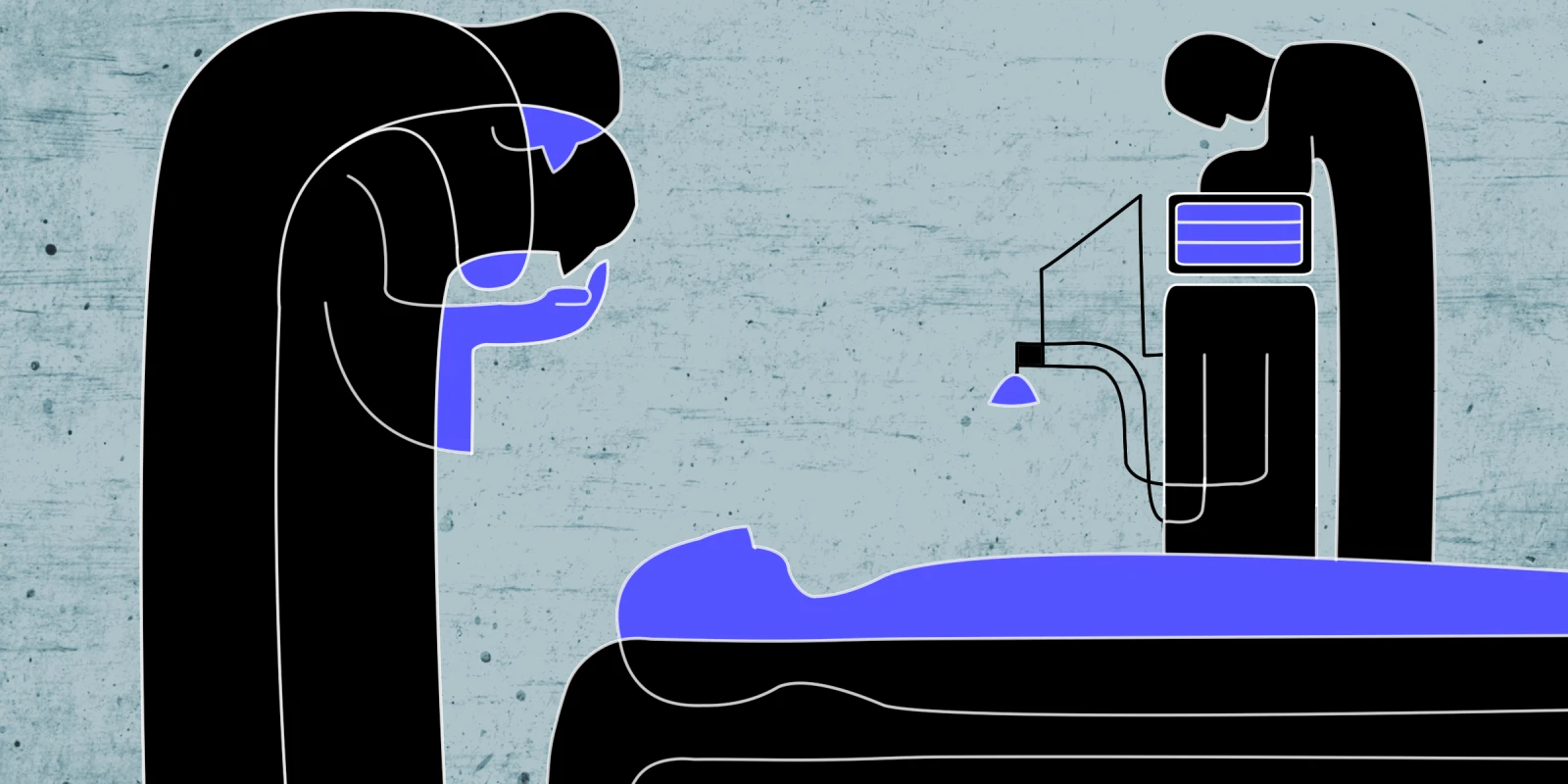

Throughout this bewildering yet deeply personal experience, two figures guided the conversation and helped close the final chapter to Agong’s full and rich life. A first-year resident empathetically described what we were up against: blood cancer, pulmonary complications, and a subdural hematoma at risk of rebleeding. As a medical student, I wanted all the details and facts surrounding the diagnosis and asked for the pathology report. The resident said he was busy tending to other patients but that he’d drop some papers off the next day, a task he could have easily forgotten due to his obligations. He did not forget, and the pathology report provided me solace in a way nothing else could have at the time.

The second figure that played a pivotal role during the menagerie was the oncologist who delivered the somber news of a virtual impossibility of recovery. He was frank, curt, and, some might even say, cold. I cannot imagine the number of conversations in which he had to communicate the dismal prognosis of a loved one’s disease. His realism and practicality extinguished the flames of hope of any functional recovery and steered us in the direction towards end-of-life care. His honesty was refreshing, despite our disbelief and denial of Agong’s disease severity.

In the end, Agong was admitted to the hospital for less than a week before his passing. From the time we were given the bitter reality that he was going to die, he stayed valiantly alive for three days. Tragedy, especially the death or impending death of a loved one, brings a family together in a way no other life event could. It is a moment to pause, reflect on the fragility of life, and focus on what truly matters. The strength my family portrayed during this adversity was unexpected and admirable for a group of people who are all fiercely independent — and avoid all things macabre. I especially admired my father, who had to make the many spur-of-the-moment decisions for immediate medical testing, imaging studies, and bedside procedures. Throughout it all, he was there every waking hour of the day, always sleeping a stone’s throw away on hospital waiting room chairs.

Agong’s pain was insurmountable in the last few days and it was decided that with palliative measures, maximal comfort and ease of symptoms were the goals. Gone were the glucose, saline, and insulin drips that required IV access which severely bruised Agong’s hand. He was now only on a nasal cannula for oxygen flow and a potent sedative. When he was in a comatose state from the sedative and cancer burden, I moistened his chapped lips with an oral sponge swab stick — a last act of reverence to his request for water just days prior, which was withheld at the time due to high risk of aspiration.

In his final moments, Agong was surrounded by those who loved him. And while he might be gone, he eternally lives in the vibrant memories of those who cherished him. Even today, I could almost make out his final breathy words to me: “Study well in school and be careful driving on highways.”

Brian Tung is a second-year medical student at New York Medical College in Valhalla, NY. He earned his bachelor’s degree in neuroscience at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, MD. During his free time, he enjoys hiking in the great outdoors, eating out at new restaurants, and exploring museums and art galleries.

Illustration by April Brust